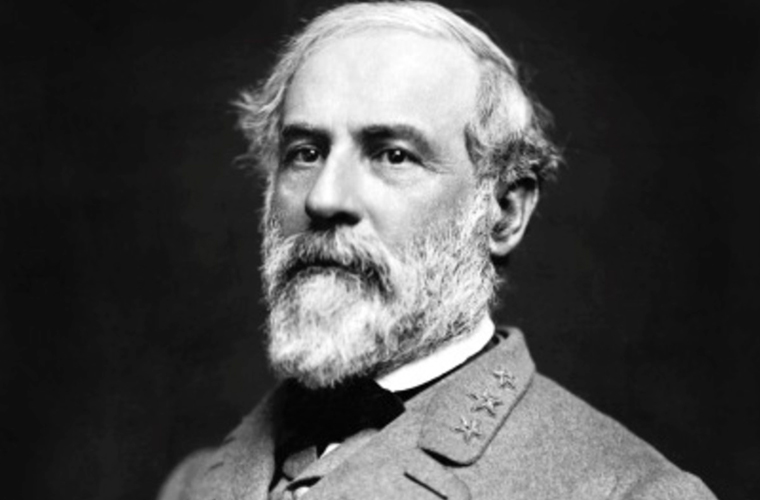

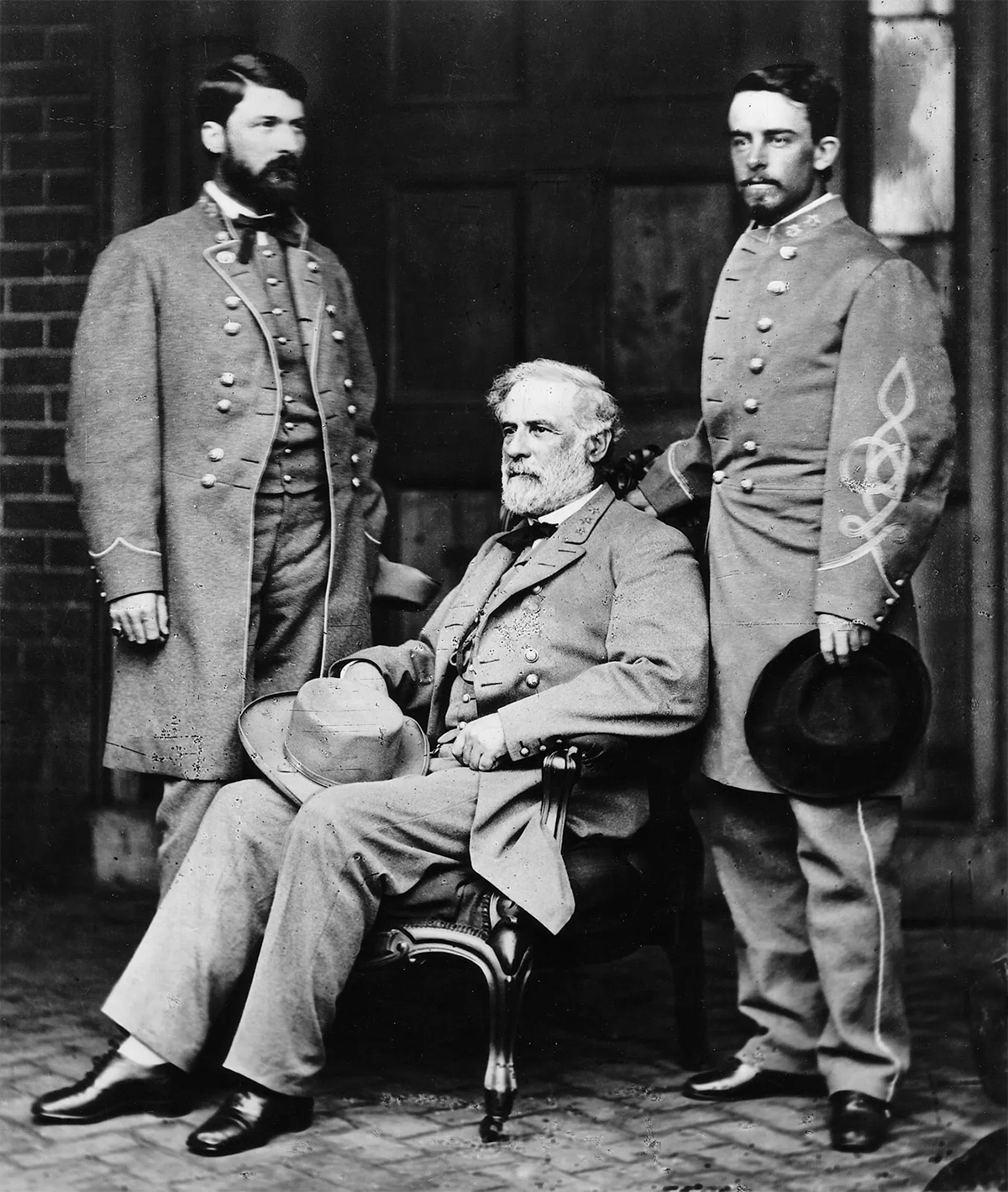

Robert E. Lee was an American soldier and Confederate general during the American Civil War. He was born on January 19, 1807, in Stratford Hall, Virginia, and died on October 12, 1870, in Lexington, Virginia. Lee came from a prominent Virginia family and graduated from the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1829. He served in the United States Army for over 30 years, gaining valuable military experience and recognition for his abilities. He distinguished himself in the Mexican-American War and later served as Superintendent of the United States Military Academy.

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, Lee was offered command of the Union Army but declined due to his loyalty to his home state of Virginia, which had seceded from the Union. He instead joined the Confederate Army and quickly rose through the ranks. Lee became the commanding general of the Army of Northern Virginia, one of the most prominent Confederate armies.

Lee’s military leadership and tactical brilliance earned him respect on both sides of the conflict. He achieved several notable victories against superior Union forces, including the Seven Days Battles, Second Bull Run, Fredericksburg, and Chancellorsville. However, his most famous and fateful decision came in 1863 during the Battle of Gettysburg. Lee led his army into Pennsylvania but was defeated in a costly and decisive three-day battle.

In 1865, with the Confederacy facing defeat, Lee surrendered to Union General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House, effectively ending the Civil War. After the war, Lee advocated for reconciliation and worked to rebuild the devastated South.

Now we are in a state of war, which will yield nothing. The whole South is in a state of revolution…and though I recognize no necessity for this state of things, and would have forborne and pleaded to the end for a redress of grievances, real or supposed…I had to meet the question of whether I should take part against my native state. With all my devotion to the Union and the feeling of loyalty and duty of an American citizen, I have not been able to make up my mind to raise my hand against my relatives, my children, and my home. I have, therefore, resigned my commission in the Army, and, save in defense of my native state, with the sincere hope that my poor services may never be needed, I hope I may never be called on to draw my sword.

Robert E. Lee’s reputation has been a subject of debate and controversy. While he is widely admired for his military skills, his association with the Confederate cause and defense of slavery has made him a contentious figure. In recent years, there has been increased scrutiny and debate over Confederate symbols and monuments, including those dedicated to Lee.