Born Elmer Gerard Pratt in Louisiana, 1947; son of Eunice Petty Pratt and her husband, a scrap metal dealer; married Sandra Pratt, who was murdered in 1971; married Asahki Ji Jaga, 1976 (the couple divorced in 1995, but plan to remarry); two children (conceived during conjugal visits), Hiroji, 15, and Shona, 18. Education: University of California at Los Angeles. Politics; radical left; former member of the Black Panther Party. Religion: Catholic.

Growing up in the South during the pre-Civil Rights era, Pratt experienced the injustice of segregation—but also the security of living in a close-knit black community. “The situation was pretty racist, on the one hand; on the other, it was full of integrity and dignity and the pride of being a part of this community … the values, the work ethic, very respectful to everyone,” Pratt told Heike Kleffner of Race and Class Magazine

As a child, Pratt witnessed lynchings and other activities of the Ku Klux Klan—experiences that shaped his attitude toward violence and eventually led to his decision to join the Black Panther Party. “There was a constant state of warfare, because of the racial polarization,” he was quoted as saying in Race and Class Magazine “Martin Luther King, the civil rights movement, etc., was not that popular there (in Louisiana), because we were raised on the self-defense principle of fighting and defending our people from those kinds of racist attacks.”

While his parents were not well-off, they managed to send the first six of their seven children to college. After Pratt’s father suffered a stroke in 1965 and was no longer able to work, Pratt volunteered to join the military, to help support the family. As a long-range reconnaissance expert with the 82nd Airborne, Pratt served two tours of duty in Vietnam. He was awarded a Purple Heart and a Silver Star, and three years later left the military with the rank of sergeant.

In 1968, five of his siblings were living in Los Angeles, and they convinced Pratt to enroll at UCLA, which had initiated a “High Potential Program” intended to help minorities pursue a college education. That fall, Pratt began to attend classes at the Westwood campus. There, he met Alprentice “Bunchy” Carter, who had also grown up in Louisiana and was one of the original members of the Black Panther Party—a group that Pratt soon joined. It was Carter who gave Pratt the nickname “Geronimo,” to honor his fierce commitment to the party. “Being fresh from Vietnam, plus being from the South, opened my eyes to a lot of things,” Pratt was quoted as saying in Race and Class Magazine.

After Carter and another Panther leader were killed by a rival organization, Pratt was quickly promoted in the party hierarchy. By 1969, at age 22, he had become the party’s deputy minister of defense—bypassing 36-year-old Panther Julius Butler, and causing a rivalry between them. That rivalry would become important later when Butler became a key prosecution witness in Pratt’s murder trial.

As defense minister, Pratt got into trouble with the law several times over the next few years: he was arrested for possessing a pipe bomb and for assault with a deadly weapon, though neither charge stuck. In late 1969, he was ordered by Huey Newton to “go underground” to build a “revolutionary infrastructure” in the Deep South. Pratt spent the rest of that year traveling around Alabama, Louisiana, and Texas, gathering weapons and fortifications for Newton’s latest directive for the party: a separate nation for blacks.

By 1970, Pratt was under surveillance by the Los Angeles Police Department and the Los Angeles Attorney’s Office. Although it was not known at the time, both offices were in contact with the FBI; according to FBI documents released in the late seventies, Pratt was one of the “key black extremists” that the FBI wanted to “neutralize.”

Arrested for 1968 Murder

On December 8, 1970, Pratt was arrested in Dallas, Texas, and extradited back to California, charged with involvement in a 1969 shootout. Later, he was indicted as one of the two suspects in the unsolved “tennis court murder.” Two years earlier, on December 18, 1968, Caroline Olsen and her husband, Kenneth Olsen, were about to begin a game of tennis on a Santa Monica court when two men, described as black and in their twenties, robbed them at gunpoint. During the bungled robbery, which netted just $ 18, Caroline Olsen was shot to death and Kenneth Olsen was wounded.

“At the time that I was indicted, it was just another charge that they threw in to maintain a no-bail situation …,” Pratt told Race and Class Magazine in 1992. “Eventually, it became more and more obvious to us that the murder charge was something that they were really going to try and press.”

Pratt contended he was at a Black Panther meeting in Oakland, 400 miles away, the night of the shooting; but his alibi was substantially weakened when many high-ranking Panthers refused to confirm it. By 1970, the party was split by a bitter feud that would eventually destroy it. On one side were Huey Newton and Bobby Seale, who renounced violence; on the other were Eldridge Cleaver and his followers—including Pratt— who favored more militant methods. While Eldridge Cleaver’s wife, Kathleen Cleaver, and two other Panthers testified in support of Pratt, Huey Newton ordered members of his faction not to testify at the trial. A more damaging piece of testimony came from Kenneth Olsen, who identified Pratt as the killer.

The final piece of evidence came from Pratt’s rival, Julius Butler, who testified that Pratt had confessed the murder to him. Days after Pratt had expelled him from the Panthers in 1969, Butler gave a contact at the Los Angeles Police Department an “insurance letter,” to be opened only if he were killed. In the letter, Butler implicated Pratt in the unsolved murder—the first time Pratt had been tied to the crime. Later, allegedly under pressure from the FBI, Butler authorized the LAPD to open the letter.

Between the unconfirmed alibi, positive identification, and alleged confession—which Pratt denied to no avail— the prosecution’s case was convincing. At the end of the 1972 trial, Pratt was convicted and sentenced to 25 years to life in prison.

Pratt spent the first eight years of his sentence at San Quentin, in solitary confinement; but after Amnesty International took up his case, a jury determined that keeping him in solitary confinement was illegal. Several years later, he was transferred to Folsom. By the time he was finally released, Pratt was being held in Mule Creek State Prison in lone, Amador County, California. In his 27 years in prison, Pratt was turned down for parole 16 times, because he refused to admit guilt or renounce his politics.

In 1976, he married Asahki Ji Jaga; his first wife, Sandra, had been murdered in 1971 by the Newton faction of the Black Panther Party. At Folsom, Pratt was allowed two conjugal visits a year; during these visits, his wife conceived two children, a daughter, Shona, and a son, Hiroji.

Conflicting Evidence Discovered

Shortly after Pratt was jailed, the case against him began to unravel. First, it came to light that Kenneth Olsen had originally chosen another man out of a police line-up. In his sworn testimony, Olsen had claimed that he had positively identified only one suspect—Geronimo Pratt.

Next, the FBI’s role in Pratt’s conviction came to light. In 1975, a congressional committee released its explosive findings about the FBI’s covert counter-intelligence program, COINTELPRO. During the sixties and seventies, the agency deliberately tried to disrupt political groups that it deemed too radical—authorizing illegal phone taps and IRS audits, using informants, and trying to cause dissension within the groups. By 1968, the committee discovered, that the Panthers were COINTEL-PRO’s primary target; FBI documents explicitly called for Pratt, along with other leaders, to be “neutralized.”

The most significant piece of evidence, however, surfaced in 1980. According to FBI documents, the key prosecution witness, Julius Butler, had acted as an FBI informant—and had denied it under oath during Pratt’s original trial. During the trial, neither jurors nor defense attorneys were told of any FBI involvement in the case.

And finally, after Huey Newton’s death in 1989, six Panthers came forward to testify that Pratt had indeed been present at the 1968 meeting in Oakland. “It has been on my mind all of these years that I should have testified,” Bobby Seale wrote in his 1991 affidavit.

Based on the mounting evidence, Pratt’s attorneys tried four times to get him a new trial—but met with no success. After their fourth appeal was rejected in 1993, Pratt’s primary lawyer, Stuart Hanlon, contacted Jim McCloskey, head of Centurion Ministries, which specializes in exonerating wrongly convicted prisoners. After researching the case, McCloskey became convinced that Pratt was innocent. In 1993, he was eventually able to persuade District Attorney Gil Garcetti to review the case—though the hearing was delayed for another three years.

By the time of Pratt’s March 1996 hearing, his case had become a cause celebre, drawing support from Amnesty International, the American Civil Liberties Union, several members of Congress, Coretta Scott King, and Nelson Mandela. Even members of the original jury that convicted Pratt had joined his defense. Jeanne Hamilton, along with two other jurors, signed affidavits stating if they had known that Butler was an FBI informant, and Olsen had made a prior identification, they would have never voted guilty. “We were victims. We were pawns of the government. We were set up …,” Hamilton was quoted as saying in an Associated Press wire story. “In my heart of hearts, I think he’s innocent. There’s no question in my mind.”

Pratt’s Conviction Overturned

On May 29, 1997, an Orange County judge, Superior Court Judge Everett Dickey, overturned the conviction and ordered a new trial for Pratt. His ruling was based on the fact that prosecutors had not told the defense Butler was an infiltrator and paid informant for the FBI and police. According to Greg Goldin, writing in The Nation, “Judge Everett Dickey’s terse opinion was an indictment of everything we now know about the repressive methods used during the sixties by the state to destroy dissent.”

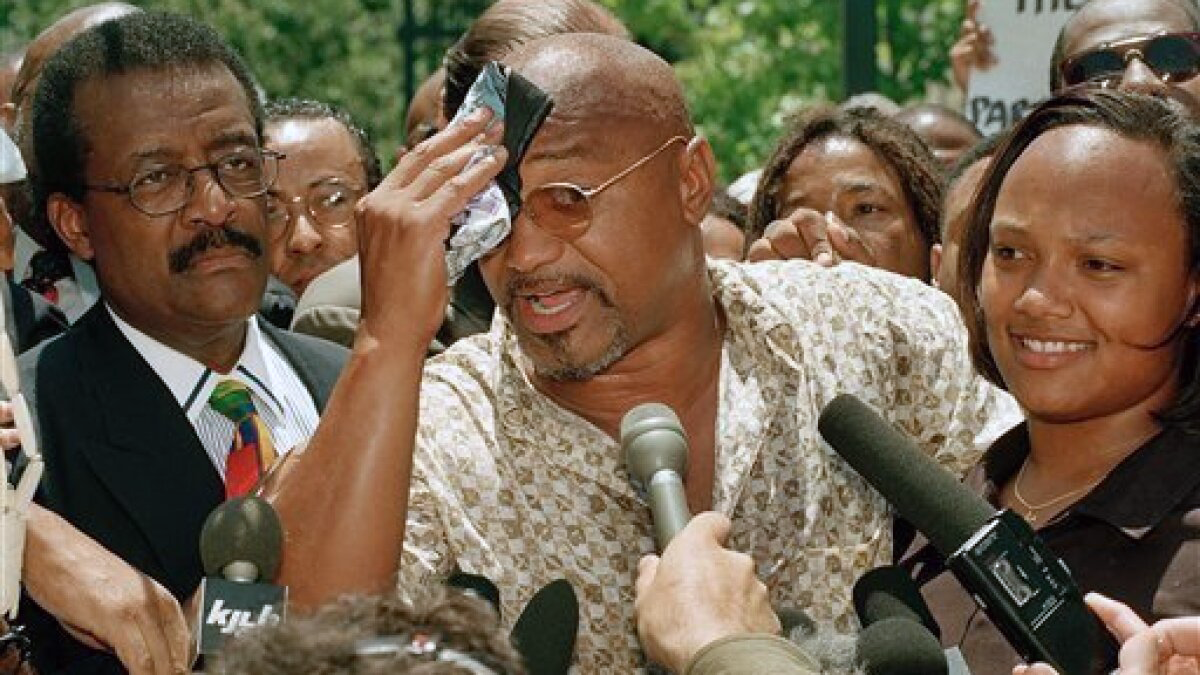

On June 10, 1997, in front of a courtroom packed with 1960s activists, Judge Dickey ordered Pratt to be released on $25,000 bail. He had spent 27 years behind bars. “It’s the most satisfying victory in my career,” Cochran was quoted as saying in Jet. “I’ve been fighting for this for 25 years.”

Pratt was released in time to watch his son, Hiroji, go through his eighth-grade graduation ceremony. Later, he returned to Louisiana to see his 94-year-old mother, Eunice Petty Pratt, whom he had not seen since 1974.

District Attorney Garcetti is seeking to get the conviction reinstated; failing that, he could retry Pratt. When Pratt was finally released, Stuart Hanlon challenged Garcetti, “If you’re so convinced Mr. Pratt is guilty, then you get in there yourself and retry the case. Let’s forget about the appeal. Let’s go to trial in 60 days” (quoted by the Frontline News Service). Garcetti has hinted that he would not retry the case if the appeal is unsuccessful.

Through all the years he spent in prison, Pratt has maintained his radical politics. “I want to be the first one to call for a new revolution,” he told a group of people gathered to welcome him to his Marin City, California home (quoted in the San Francisco Examiner) Since then, Pratt has delivered speeches at a Congressional Black Caucus Dinner and at the University of Southern California. In his speeches, he has called for the formation of a movement based on respect for elders in the African American community, and a national plebiscite to determine actual from supposed black leaders. Hollywood is also interested in Pratt: numerous filmmakers have approached him, wanting to make a movie based on his story.