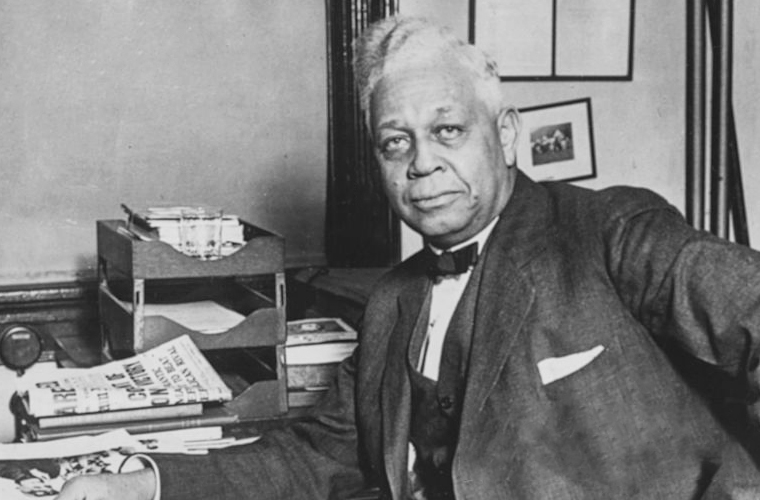

Oscar De Priest made history as the first African American elected to Congress in the 20th century, breaking a 28-year absence of black Representatives. His victory marked a significant milestone, signifying a new era of black political organization in urban areas, particularly in Chicago. Although his legislative accomplishments were modest, De Priest’s election symbolized hope for African Americans and laid the groundwork for future black Members of the House and Senate.

Oscar Stanton De Priest was born to former slaves Alexander and Mary (Karsner) De Priest in Florence, Alabama, on March 9, 1871. His family later moved to Kansas to escape poor economic and social conditions in the aftermath of Reconstruction. De Priest settled in Chicago in 1889, where he established himself as a successful businessman and became involved in local politics. His rise in the political arena was facilitated by Chicago’s budding machine organization, eventually leading to his election as Chicago’s first black alderman in 1915.

De Priest’s pivotal moment came with the sudden death of influential Chicago Representative Martin Madden, which led to De Priest being selected as the nominee for the lakeshore congressional district encompassing Chicago’s Loop business section and a predominantly black area that included the famous Bronzeville section of the South Side. His election to Congress in 1928 marked the beginning of continuous African-American representation in the South Side district of Chicago.

De Priest faced numerous challenges upon entering Congress, including attempts to exclude him due to past investigations and resistance from some southern Democrats. His presence in Congress challenged the prevailing segregation practices, exemplified by the controversy surrounding First Lady Lou Hoover’s invitation to Mrs. Jessie De Priest to a White House tea. De Priest also confronted discriminatory practices within the Capitol, advocating for equality in various aspects of congressional protocol.

As the only African American in Congress during his three terms, De Priest found himself representing not only his Chicago district but also the entire black population of the United States. He introduced several bills aimed at promoting civil rights and addressing economic disparities, although many of his legislative efforts were unsuccessful. Notably, he succeeded in adding an antidiscrimination rider to a significant unemployment relief and reforestation measure, marking a notable triumph in his congressional career.

De Priest’s refusal to support Roosevelt’s economic measures and his loyalty to the Republican Party ultimately cost him his seat in the House. He faced a formidable challenge from Arthur Mitchell, a former Republican lieutenant who switched to the Democratic Party and became an ardent supporter of Roosevelt and the New Deal. Mitchell’s victory marked a shift in African American political allegiance from the Republican Party to the Democratic Party, reflecting dissatisfaction with the GOP’s response to the plight of Black Americans during the Depression.

Following his tenure in Congress, De Priest remained active in Chicago politics and his real estate business. Although he did not regain his congressional seat, his pioneering role in African American political representation left a lasting legacy. His efforts paved the way for future black Members of Congress and contributed to the ongoing struggle for civil rights and equality in the United States.

Oscar Stanton De Priest’s contributions to American politics and civil rights serve as a testament to his resilience and determination in the face of significant challenges. His pioneering role as the first African American elected to Congress in the 20th century continues to inspire future generations and remains an integral part of African American political history.