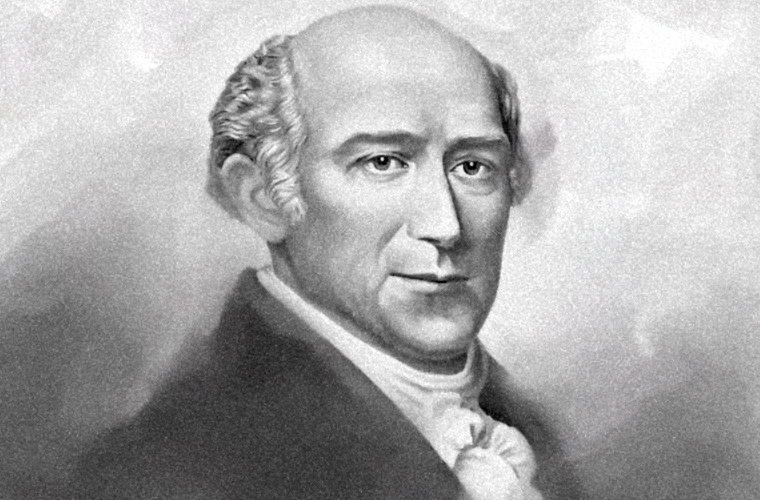

Richard Riker (September 9, 1773 – September 26, 1842) was an American lawyer and politician from New York, who served as the first district attorney of what is now New York County, and as recorder of New York City.

Riker studied law at the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University) under Rev. John Witherspoon and was admitted to the New York state bar in 1795. In 1801, he was appointed to the newly created office of the District Attorney of the First District, where he prosecuted cases in New York, Queens, Kings, Richmond, Suffolk, and Westchester counties. Before 1801 the New York State Attorney General had personally prosecuted cases. During his tenure, he also served as a member of the New York State Assembly in 1806, representing New York City. Riker remained in office until 1810 and then served as district attorney again from 1811 to 1813.

He served three non-consecutive terms as the Recorder of New York City between 1815 and 1838. In this position, Riker abused the Fugitive Slave Act to send free blacks to the South to be sold into slavery. By the 1830s, abolitionists considered Riker a member of the “Kidnapping Club”, along with Daniel D. Nash and Tobias Boudinot, who “boasted that he could ‘arrest and send any black to the South.'” In 1828, Riker was also made the subject of a satirical poem, “The Recorder” by Fitz-Greene Halleck, which mockingly compared him and other members of the New York party machine to classical figures like Julius Caesar.

Riker was a close friend of DeWitt Clinton, and both were supporters of Alexander Hamilton, leading to duels with supporters of Hamilton’s rival Aaron Burr. Riker served as Clinton’s second in a duel with John Swartwout on July 30, 1802, at the dueling grounds in Weehawken, New Jersey, where Swartwout was wounded in the leg. On November 21, 1803, Riker dueled with John Swartwout’s brother, Brigadier General Robert Swartwout, at Weehawken in defense of Clinton’s honor. Riker was shot in the leg at this duel, giving him a permanent limp.

He was born in Newtown, Queens County, New York, the son of Congressman Samuel Riker and Anna Lawrence Riker, niece of Jonathan Lawrence. In March 1807, Riker married Janette Phoenix, daughter of Daniel Phoenix (ca. 1740-1812, who served as New York City Treasurer, 1784-1809), and they had six children. He was a member of the prominent and wealthy Riker family, which owned Rikers Island, now New York City’s primary jail complex, until 1884. The island’s name has been the subject of some controversy and has drawn comparisons between Riker’s kidnappings and the disproportionately African-American population of the jail.