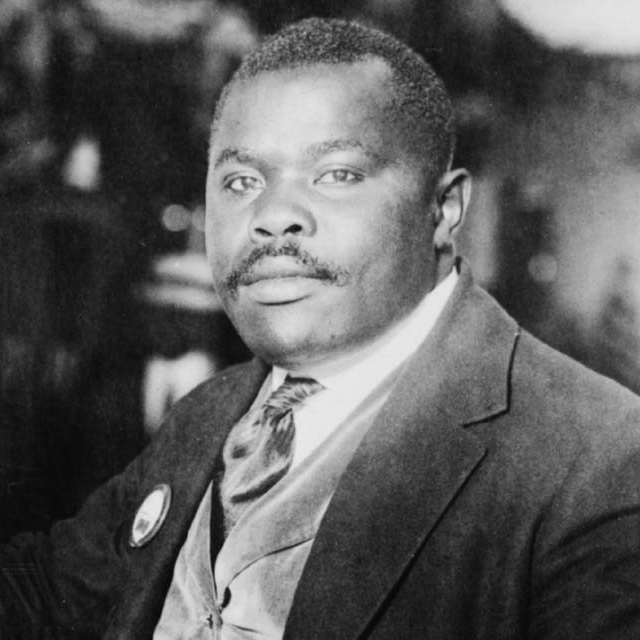

Marcus Garvey is famed for being Jamaica’s first national hero who advocated for Black nationalism in Jamaica and particularly in the United States.

Born on this day (August 17) in, 1887, Garvey traveled around many countries observing the poor living conditions under which black people were working at the time.

In 1914, he started the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) in Jamaica, which protested against racial discrimination and encouraged self-government for black people all over the world. He also founded the Black Star Line, a shipping and passenger line that promoted the return of the African diaspora to their ancestral lands.

But his struggles would begin after his arrival in the U.S. in 1916, where he preached his doctrine of freedom to the blacks who were being oppressed. His actions would not only go down well with U.S. officials but also with some black leaders and intellectuals at the time, resulting in disagreements over how racial equality should be pursued.

Marcus Garvey (from second right)

Marcus Garvey (from second right)

Garvey had by then advanced a Pan-African philosophy which inspired a global mass movement known as Garveyism. Even though his followers saw him as a long-awaited savior, some black leaders condemned his methods and his support for racial segregation.

Things got worse when his black nationalism got him to a position where he was “inaugurated” as president of Africa. His love for flowing robes, gold-tasseled turban, and grand titles began to infuriate some black personalities who saw him as a charlatan and an embarrassment.

One of his worst critics would be W.E.B. Dubois. At the time when equal rights were sought after by many people in various ways, it is documented that the most effective of those methods came from two highly influential men: Garvey and DuBois.

Booker T. Washington, who was then the most respected black man in America, had campaigned for black people to accept being subhuman and not having rights. Both Garvey and DuBois had been against his stance and had pushed for what Washington probably couldn’t – the advancement of civil rights.

But Garvey and DuBois would have differences that were mainly ideological and this would ruin any relationship the two influential black political leaders of the 1920s had. Having come from separate backgrounds, they had different outlooks on the destiny of the African American race.

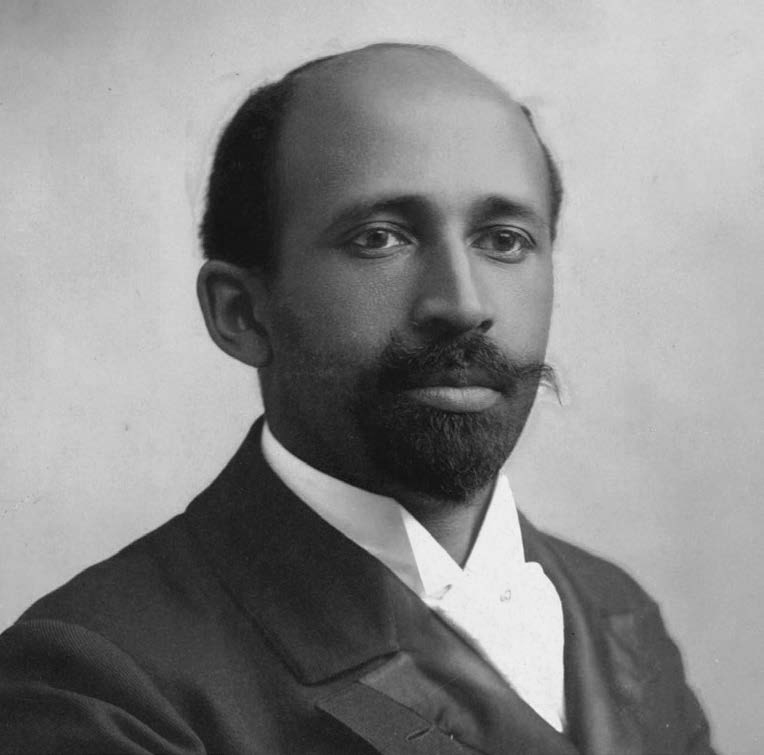

W.E.B Du Bois

W.E.B Du Bois

DuBois, who was from a more privileged background, worked on improving the condition of African Americans, but he wanted to do this by working with liberal whites through his organization the NAACP, an article on msu.edu said.

Garvey grew up in an impoverished Jamaican community and his ideas were centered on blacks helping blacks, without any dependence on whites.

How the two first met

Garvey and DuBois first met in May 1915 in Jamaica when the latter was on a visit to the Caribbean country. At the time, DuBois was already a black leader in the U.S. while Garvey had just a month before established his UNIA in Jamaica.

DuBois, during his visit, received a friendly welcome-letter by Garvey and the two later met in person. There, Garvey told Dubois about his plans and his hope to get his support. A year later, Garvey came to the U.S. for a speaking tour to raise money for a project in Jamaica. He invited DuBois to his first lecture but he declined the invitation, writes Eva Kiss in the 2001 Seminar Paper: The Conflict Between Marcus Garvey and W. E. B. Du Bois.

Meanwhile, Garvey had decided that the U.S. was the ideal place to advance his ideas and so he stayed, continued his speaking tours, and soon gained a large following before finding the U.S. branch of the UNIA in 1918 and his UNIA newspaper, “The Negro World.”

Garvey believed that whites would never come to accept blacks and thus, he proposed that black Americans return to Africa, “where they would live as part of a majority population and perhaps have real political power,” an article on NPR noted.

DuBois, however, “wanted to push shining examples of black citizenry front and center for white America to see, people so accomplished it would be hard to deny them their rightful place in society,” the article added.

These differences began the conflict between the two. DuBois once described Garvey as “without doubt the most dangerous enemy of the Negro race in America and in the world,” though Garvey believed that Du Bois was prejudiced against him because he was a Caribbean native with darker skin.

These differences began the conflict between the two. DuBois once described Garvey as “without doubt the most dangerous enemy of the Negro race in America and in the world,” though Garvey believed that Du Bois was prejudiced against him because he was a Caribbean native with darker skin.

DuBois felt that Garvey’s program of complete separation, which was a form of surrender to white supremacy, threatened the gains made by his own NAACP movement. Hence, by the early 1920s, DuBois and Cyril Briggs, chief of the African Black Brotherhood and editor of Crusader magazine started an active campaign aimed at getting Garvey out.

By then, Garvey’s life had been met with controversies, and this largely had to do with his Black Star Line, the all-black steamship company that was launched in 1919 to rival the luxurious White Star Line, whose flagship was the Titanic.

There were doubts about the Black Star Line, and even though some of these concerns were published in newspapers and magazines, DuBois went further by launching an investigation of the operations of the company in the monthly magazine of the NAACP, the Crisis.

DuBois published his results in a two-part essay, in the Crisis issues of December 1920 and January 1921, simply called “Marcus Garvey”.

“The first part of the two is an analysis of Garvey himself, the second one more like a financial report. He critiques Garvey’s failures but not his program and keeps a quite neutral tone, that just sometimes gets a tendency to insult. Garvey is characterized as honest and sincere but as well as dictatorial and unable to get along with co-workers, and explains the real state of the Black Star Line that was not as good as Garvey presented it and says that Garvey thinks of everything as too easy before he lists Garvey’s mistakes and finally hopes that Garvey will not produce too much damage,” writes Eva Kiss in the 2001 Seminar Paper.

Meanwhile, the Black Star Line started having issues with stock sales, and attempts to raise money for a fourth ship led to Garvey being charged with mail fraud.

The accusation was that the company had displayed a nonexistent ship and was grossly misrepresenting the firm in stock sales.

Even though officials did not get any evidence that Garvey had intended to fill his pockets, during his trial on February 23, it was reported that an inspection of the Black Star Line books showed that there were “clear improprieties, lost receipts, in one instance a $476,000 chunk that simply couldn’t be accounted for.”

Basically, Garvey was accused of running the company into liquidation, and he was quickly convicted.

Marcus Garvey

Marcus Garvey

On June 23, 1923, Garvey was sentenced to five years in prison but he appealed all the way to the Supreme Court, and still went ahead to stage rallies across Harlem about his black nationalism movement till late August 1924.

He, however, lost his appeal and in February 1925, he began his sentence. Two years later, President Calvin Coolidge, who acknowledged that Garvey’s prosecution had been politically motivated, commuted the sentence.

Despite the disagreements between Garvey and DuBois, the two influential black leaders had a lasting impact on generations to come and would impact the fight for racial equality.