A Dark Chapter in Georgia’s Racial History

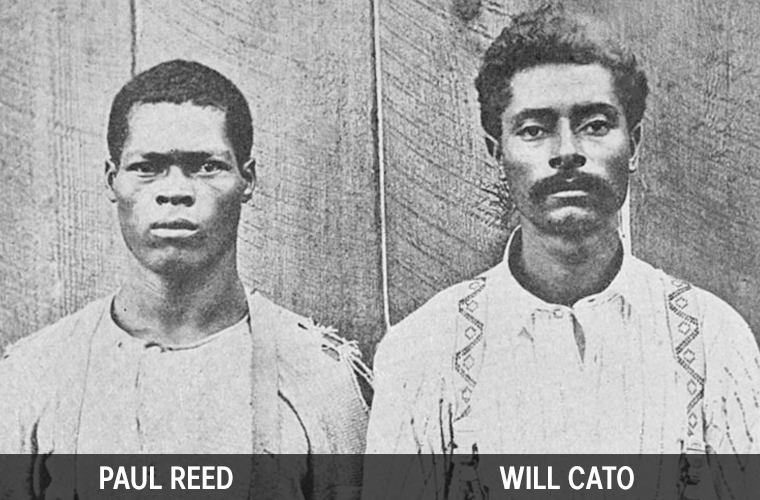

In August 1904, the small town of Statesboro, Georgia, became the epicenter of one of the era’s most brutal racial atrocities. Two Black men, Will Cato and Paul Reed, were arrested for the horrific murder of white farmer Henry R. Hodges, his wife, and their three children, whose home had been set ablaze in what authorities described as a robbery gone wrong. To prevent immediate violence, the suspects were held in Savannah, 50 miles away, allowing tempers to simmer. But the fragile peace was shattered when they were returned to Statesboro for trial two weeks later.

An all-white jury swiftly convicted Cato and Reed, sentencing them to death by hanging. Before the judge could finish speaking, a mob of about 1,000 armed white men—many from neighboring counties, fueled by whiskey and rumors—stormed the Bulloch County Courthouse. With the help of the local sheriff and deputies, they overpowered the remaining unarmed guards, seized the men, and dragged them through the streets. Nooses around their necks, the prisoners were hauled two miles northwest of town to a remote stump, where they were chained, doused in 10 gallons of oil each, and burned alive amid cheers from the crowd. Spectators, including families with children, collected charred bone fragments as souvenirs; two boys even presented pieces to the judge the next day. Though a grand jury later examined 50 witnesses, no lynchers were indicted—public sentiment deemed the act a necessary deterrent against Black “criminality.”

This lynching was no isolated punishment; it ignited a wave of terror. The mob targeted any Black person seen as a threat, whipping women pulled from church for allegedly bumping white girls on the sidewalk and beating others nightly. An unidentified Black man was riddled with bullets on Lott’s Bridge, while elderly Albert Roberts and his 17-year-old son were shot in their home in a random attack. Fearing further reprisals, hundreds of Black residents fled Statesboro, crippling local cotton and turpentine industries reliant on their labor.

Sensationalized Press and Mob Frenzy

The Savannah Morning News played a shameful role in stoking the flames. Weeks before the trial, the paper printed inflammatory headlines like “WILL LYNCH PRISONERS AS SOON AS CONVICTED,” alongside unsubstantiated tales of the Hodges children pleading for mercy with their pennies. These stories, which presumed guilt and hyped a fictional “Black Mafia” of ministers plotting against “mean” whites, drew vigilantes from afar. A reporter embedded with the mob attended their planning meetings—complete with oil stockpiles and assigned committees—but withheld details to avoid “trouble,” even as rumors prompted military intervention from Savannah. The journalist later photographed the burning men before, during, and after, turning horror into spectacle.

In contrast, Black-owned papers like the Savannah Tribune decried the injustice. Formed post-Reconstruction to combat eroding civil rights, the Tribune reported on November 5, 1904: “The grand jury adjourned without indicting any rioters… It was expected… that no bills would be found.” It highlighted the futility of seeking justice in a system that excluded Black jurors and voices, noting white willingness to “forgive the lynchers” for protecting against the “dangerous Negro element.” As W.E.B. Du Bois had warned in his 1903 book The Souls of Black Folk, “The problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color-line”—a divide enforced by public spectacles of violence, rarely punished and often celebrated.

Echoes of a Broader Terror

The Cato-Reed horror was emblematic of the era’s racial bloodshed, which dominated headlines. The Morning News chronicled similar atrocities: the August 28, 1904, mob shooting of Sebastine McBride in Portal; the lynching of suspect A.L. Scott the next day; and the 1902 disappearance of Richard Young in Savannah, accused of murdering young Dower Fountain and assaulting his mother during a burglary. Young’s relatives chased him down, allegedly burning him on Ogeechee Road, but officials dismissed the case amid vague denials and wild theories of river pirates.

Black lives rarely appeared in the white press except as victims or villains. Eva Poole, a 92-year-old survivor of that time, recalled the suffocating restrictions: “You didn’t have privileges; it was just like you were in slavery almost. You couldn’t say what you wanted, go where you wanted, or do what you wanted.” Her family shunned the Morning News, but working in a white household from 1915, she overheard discussions of its stories. Once, a phone call sent her employer rushing off “to Bulloch County to help somebody try and lynch someone,” gun in hand—a chilling reminder that such violence was not just history, but a lived, ongoing threat.