By Ronald G. Shafer

On a hot August day in 1890, delegates gathered at Mississippi’s Capitol Building in Jackson to begin work on a new state constitution. The overriding topic was the “suffrage question.”

The convention’s president, Solomon Saladin Calhoon, a White county judge, put the voting issue bluntly. “Let’s tell the truth if it bursts the bottom of the universe,” he said. “We came here to exclude the Negro. Nothing short of this will answer.”

Delegates eventually adopted a literacy test and a poll tax geared to suppress the Black vote in a state with a Black majority. The “Mississippi Plan” became the model throughout the South, part of a raft of racially oppressive Jim Crow laws that ended Reconstruction.

Mississippi’s 1890 convention sought to find a way around the 15th Amendment to the Constitution, which gave African Americans the vote.

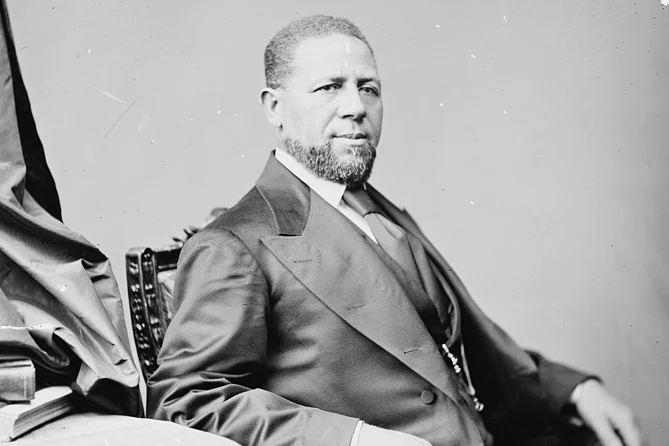

Just two decades earlier, the Mississippi state legislature had made history by electing Hiram Revels to the U.S. Senate. He was the first African American member to serve in either house of Congress. But that moment of racial progress quickly vanished.

“We came here to exclude the Negro. Nothing short of this will answer.”

After President Rutherford B. Hayes removed all federal troops from Southern states in 1877, White Democrats who’d supported slavery and the Confederacy began regaining control of the states from Black and White Republicans.

Nearly all of the Mississippi convention’s 134 delegates were White Democrats with one African American Republican. A White Republican named Marsh Cook had campaigned for a seat vowing to protect the rights of Black voters. A few weeks before the convention, his bullet-riddled body was found on a rural road.

The Jackson Clarion-Ledger lamented the murder, but added “those who did it felt they were doing their country a service in removing a man who had become so offensive.”

At the convention, one delegate candidly summarized the dilemma of White Democrats: “It is no secret that there has not been a full vote and a fair count in Mississippi since 1875 – that in plain words, we have been stuffing ballot boxes, committing perjury…carrying the elections by fraud and violence.”

He suggested a way to weed out “unqualified” voters, proposing to require that a voter “must read and write the English language or he is debarred from the privilege of voting.” Most of the state’s African Americans were former slaves who had been denied an education.

Men who can’t read “are not of a character to entrust the ballot,” the Clarion-Ledger agreed. “A plan of this kind would disenfranchise few White people, denying the ballot only to the idle and thriftless class.”

The convention adopted a provision that a qualified voter must “be able to read any section” of the state constitution, or “shall be able to understand the same when read to him.” A voter also could be questioned to determine his literacy.

Delegates rightly foresaw that White registrars would ask White voters simple questions while demanding that African Americans answer complex queries. In the following years, Black voters in the state were asked such things as “How many bubbles are in a bar of soap?”

The convention also adopted a $2 poll tax (equal to about $58 today) that disproportionately eliminated Black voters, most of whom were very poor.

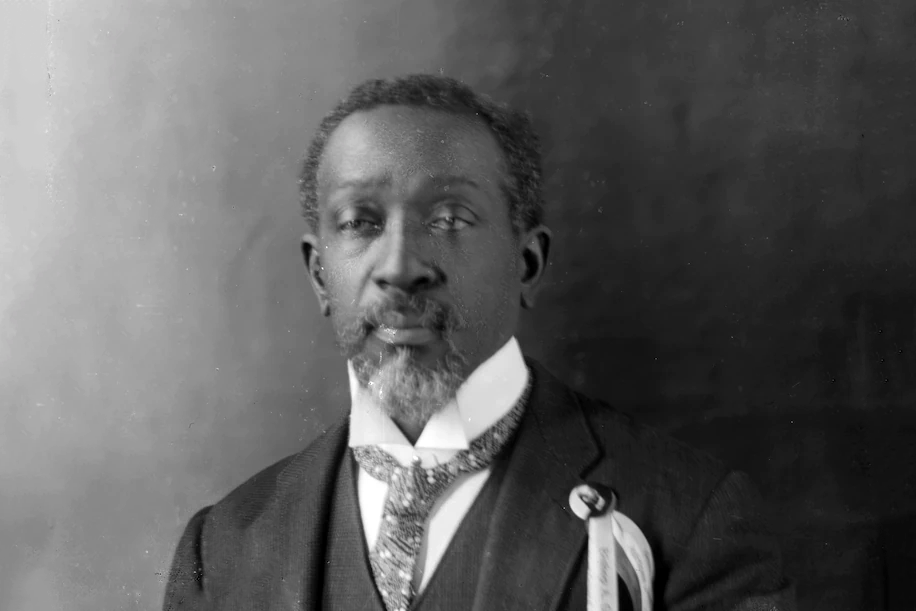

The only African American delegate, Isaiah Montgomery, supported these requirements. He had been enslaved by the brother of Confederate president Jefferson Davis of Mississippi. Montgomery, an educated and successful businessman, said that Mississippi’s uneducated Blacks would approve of the restrictions for the good of the state.

Montgomery’s optimistic view was that African Americans would be treated equally as their education level rose. “The two great races shall peaceably travel side by side, each mutually assisting the other to mount higher,” he declared in a nationally publicized speech at the convention.

Revered Black abolitionist Frederick Douglass said Montgomery “commits unconscionable treason to his race in surrendering his franchise.” Earlier African Americans from 40 counties in Mississippi had protested to President Benjamin Harrison, but he declined to intervene.

The convention adopted the constitution on Nov. 1, 1890, adding the new requirements to a provision allowing voting by male residents age 21 and older “except idiots, insane persons and Indians not taxed.”

When northern newspapers denounced the literacy test as discriminatory, one Mississippi state senator responded: “I deny that the educational test was intended to exclude Negroes from voting…the sole purpose was to exclude persons of both races who from want of intelligence are unsafe depositors of political power. That more Negroes would be excluded is true…but that is not our fault.”

That rationale was rejected a decade later by James Vardaman, the white supremacist who became governor of Mississippi in 1903. “There is no use to equivocate or lie about the matter,” Vardaman said. “Mississippi’s constitutional convention of 1890 was held for no other purpose than to eliminate the [n-word] from politics. Not the ‘ignorant and vicious’ as some of the apologists would have you believe.”

The new law took effect in the 1892 election with a dramatic impact. Only 8,615 of the state’s 76,742 Black voters qualified to cast a ballot. Soon the Mississippi approach spread to other Southern states. It remained in place for nearly 70 years until Congress passed the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

In his speech to Congress proposing the law, President Lyndon B. Johnson specifically singled out the need to eliminate literacy tests. For a Southern Black voter, he said, “even a college degree cannot be used to prove that he can read or write.”

Johnson declared: “We cannot, we must not, refuse to protect the right of every American to vote in every election that he may desire to participate in.”