Anna Pauline (Pauli) Murray was born in Baltimore on 20th November 1910. Her mother, Agnes Murray died of a cerebral hemorrhage in 1914. Her father, William Murray, was a graduate of Howard University and taught in a local high school. He suffered from the long-term effects of typhoid fever and eventually was confined to Crownsville State Hospital where he was murdered by a guard in 1923. Pauli went to live with her aunt, Pauline Fitzgerald, an elementary school teacher, and her grandparents Robert and Cornelia Fitzgerald in Durham, North Carolina.

After graduating from Hillside High School in 1926 with a certificate of distinction, she moved to New York City. Murray attended Hunter College and financed her studies with various jobs. However, after the Wall Street Crash, unable to find work, Murray was forced to abandon her studies. In the 1930s Murray worked for the Works Projects Administration (WPA) and as a teacher in the New York City Remedial Reading Project. She also had articles and poems published in various magazines. This included her novel, Angel of the Desert, which was serialized in the Carolina Times.

Murray also became involved in the civil rights movement. In 1938 she began a campaign to enter the all-white University of North Carolina. With the support of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Murray’s case received national publicity. However, it was not until 1951 that Floyd McKissick became the first African American to be accepted by the University of North Carolina. During this campaign, she developed a life-long friendship with Eleanor Roosevelt. A member of the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR), Murray also became involved in attempts to end segregation on public transport and this resulted in her arrest and imprisonment in March 1940 for refusing to sit at the back of a bus in Virginia. In 1941 Murray enrolled at the Howard University law school with the intention of becoming a civil rights lawyer. The following year she joined with George Houser, James Farmer, and Bayard Rustin, to form the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). Members of CORE were mainly pacifists who had been deeply influenced by Henry David Thoreau and the teachings of Mahatma Gandhi and the nonviolent civil disobedience campaign that he used successfully against British rule in India. The students became convinced that the same methods could be employed by blacks to obtain civil rights in America. In 1943 Murray published two important essays on civil rights, Negroes Are Fed Up in Common Sense and an article about the Harlem race riot in the socialist newspaper, New York Call. Her most famous poem on race relations, Dark Testament, was also written in that year. The poem was published as a part of a larger collection of her work in 1970 by Silvermine Press.

After Murray graduated from Howard University in 1944 she wanted to enroll at Harvard University to continue her law studies. In her application for a Rosenwald Fellowship, she listed Harvard as her first choice. She was awarded the prestigious fellowship but after the award had been announced, Harvard Law School rejected her because of her gender. Murray went to the University of California Boalt School of Law where she received a degree in law. Her master’s thesis was The Right to Equal Opportunity in Employment. Murray moved to New York City and provided support to the growing civil rights movement. Her book, States’ Laws on Race and Color, was published in 1951. Thurgood Marshall, head of the legal department at the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), described the book like the Bible for civil rights lawyers. In the early 1950s Murray, like many African Americans involved in the civil rights movement, suffered from McCarthyism. In 1952 she lost a post at Cornell University because the people who had supplied her references: Eleanor Roosevelt, Thurgood Marshall, and Philip Randolph, were considered to be too radical. She was told in a letter that they decided to give “one hundred percent protection” to the university “in view of the troublous times in which we live”.

In 1956 Murray published Proud Shoes: The Story of an American Family, a biography of her grandparents, and their struggle with racial prejudice, and a poignant portrayal of her hometown of Durham. In 1960 Murray traveled to Ghana to explore her African cultural roots. When she returned President John F. Kennedy appointed her to his Committee on Civil and Political Rights. In the early 1960s, Murray worked closely with Philip Randolph, Bayard Rustin, and Martin Luther King but was critical of the way that men dominated the leadership of these civil rights organizations. In August 1963, she wrote to Randolph and pointed out that she had: “been increasingly perturbed over the blatant disparity between the major role which Negro women have played and are playing in the crucial grass-roots levels of our struggle and the minor role of leadership they have been assigned in the national policy-making decisions.”

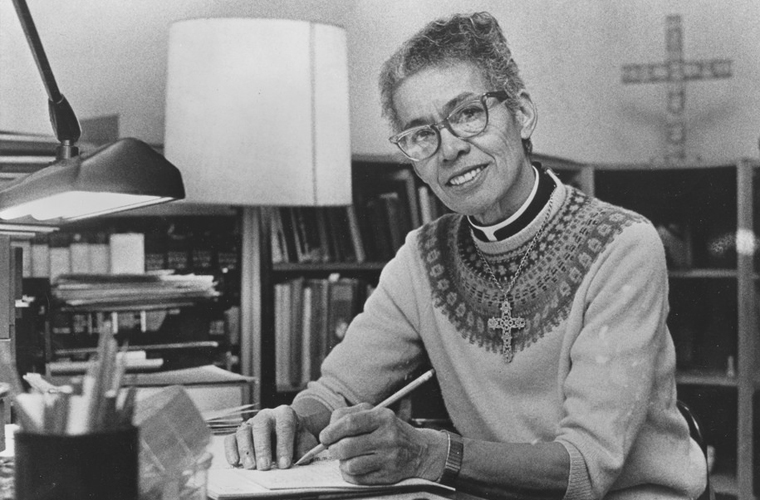

In 1977 Murray became the first African American woman to become an Episcopal priest. Pauli Murray died of cancer in Pittsburgh on 1st July 1985. Her autobiography Song in a Weary Throat: An American Pilgrimage was published posthumously in 1987. The book was re-released as Pauli Murray: The Autobiography of a Black Activist, Feminist, Lawyer, Priest, and Poet in 1987.

Since her death additional books have been published about her life and work, Anne Firor Scott’s Pauli Murray & Caroline Ware: Forty Years of Letters in Black and White; Anthony Pinn’s collection, Pauli Murray: Selected Sermons and Writings; Sarah Azaransky’s The Dream is Freedom: Pauli Murray and American Democratic Faith; Serena Mayeri’s Reasoning From Race; Patricia Bell-Scott’s The Firebrand and the First Lady, Portrait of a Friendship: Pauli Murray, Eleanor Roosevelt, and the Struggle for Social Justice; and Rosalind Rosenberg’s Jane Crow: The Life of Pauli Murray.