The March on Washington Movement (MOWM) was the most militant and important force in African American politics in the early 1940s, formed in order to protest segregation in the armed forces. The hypocrisy behind calls to “defending democracy” from Hitler was clear to African Americans living in a Jim Crow society, of which the segregated quota system and training camps of the United States military were only the most obvious examples.

Early lobbying efforts to desegregate the military had not persuaded President Franklin Roosevelt to take action. On January 25, A. Philip Randolph, the President of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, proposed the idea of a national, black-led march on the capitol in Washington, D.C. to highlight the issue.

Randolph’s proposal was a radical shift away from the strategies of leading civil rights groups at the time. First, the march would mean a vast grassroots effort mobilizing ordinary people, not political elites. Too, Randolph proposed the march as an independent action organized and led by black people themselves.

Throughout the next few months, March on Washington Committee chapters were formed to build for the march which was scheduled for July 1, 1941. It was estimated that the march would draw over 100,000 people to the capital. Both the press and long-time political activists noted the mass popularity of the march from people who had previously not been involved in protest politics.

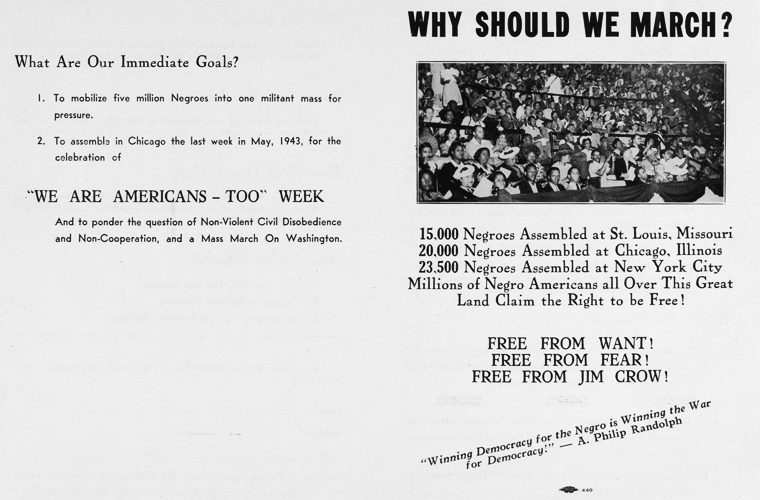

A week before the protest, an alarmed President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802, establishing the first Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC). In return, Randolph canceled the march but established the March on Washington Movement (MOWM) to hold the FEPC to its mission of desegregating the armed forces and to continue agitation for civil rights. Throughout the summer of 1942, the MOWM organized mass popular rallies. Their call for nonviolent civil disobedience, however, began to worry mainstream black organizations such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) who began to withdraw their support for MOWM activities.

MOWM’s hope that FEPC would be an independent investigative body failed in June of 1942 when Roosevelt placed it under Congressional oversight. Though hearings continued after this, neither the FEPC nor the MOWM was able to survive as a real force for challenging the racial status quo. Nonetheless, the MOWM continued until 1947.

At its zenith in 1941–1942, the MOWM signified the cohesiveness and power of a more militant, grassroots black politics, and the ability of a black-led mass movement to achieve change that formal lobbying could not and to facilitate a grassroots mobilization for civil rights. The MOWM was the model for the 1963 March on Washington, where Martin Luther King, Jr. gave his famous “I Have a Dream Speech,” and the militant Black-only politics of the MOWM foreshadowed the Black Power movement of the late 1960s.