Benjamin Hooks was an executive director of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and is the first African American board member of the Federal Communications Commission. Benjamin Lawson Hooks, the fifth of seven children, was born in Memphis, Tennessee, in 1925 to Robert B. and Bessie Hooks. Hooks’ father and uncle ran a successful photography business. His grandmother, a musician who graduated from Berea College in Kentucky, was the second African American female college graduate in the nation. With such evidence of success and hard work as his personal examples, Hooks was encouraged to do well in his studies and to prepare for higher education.

Following the Depression of 1929, an economic slump in which millions of workers lost their jobs and homes, many banks failed, and many factories closed, the Hooks family’s standard of living declined. With money so scarce during those years, African American clients could rarely afford wedding pictures or family portraits, therefore, business slowed down. Still, the family always had food, clothing, and shelter. Hooks’ parents were careful to see that all of their children kept up their appearance, attitude, and academic performance.

After high school, Hooks studied prelaw at LeMoyne College in Memphis. He successfully completed that program and then served in the army during World War II (1939–45) guarding Italian prisoners. He realized that in Memphis, these prisoners would have more rights than he did. When he left the army he continued his studies at Howard University and at DePaul University

Law School in Chicago, Illinois—no law school in the South would admit him. He returned to the South to aid in the civil rights movement rather than establish a practice in Chicago. From 1949 to 1965 he was one of the few African Americans practicing law in Memphis. He recalled in Jet magazine, “At that time you were insulted by law clerks, excluded from white bar associations and when I was in court, I was lucky to be called ‘Ben.’ Usually, it was just ‘boy.'” In 1949, Hooks met a teacher named Frances Dancy. In 1952 the couple was married.

In 1956 Hooks became a Baptist minister, and he joined the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC; an organization that worked to gain equality for African Americans) of Reverend Martin Luther King (1929–1968). He also became a bank director and the co-founder of a life insurance company. After several attempts to be elected to public office, he was appointed to serve as a criminal judge in Shelby County, Memphis, in 1965. He thus became the first African American criminal court judge in the state of Tennessee. The following year he was elected to the same position.

Hooks took part in many civil rights protests. He served on the board of the SCLC and became a life member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). He was a leader of many NAACP-sponsored boycotts (protests in which organizers refuse to have dealings with a person, store, or organization in an attempt to get the object of the protest to change its policies or positions) and sit-ins in restaurants that refused to serve African Americans. In spite of his shyness Hooks became a skilled orator (public speaker) whose quick wit and sense of humor delighted audiences. He also served as the moderator (a person who presides over a meeting) of several television shows discussing issues of importance to African Americans.

Hooks was so often in the public eye that Tennessee senator Howard Baker (1925–) submitted his name to President Richard Nixon (1913–1994) for political appointment. Nixon had promised African American voters that they would be treated fairly by the broadcast media. Thus, in 1972 he named Hooks to fill an opening on the board of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC). Benjamin and Frances Hooks soon moved to Washington, D.C. Frances Hooks served as her husband’s assistant, advisor, and traveling companion, giving up her own career as a teacher and guidance counselor. She told Ebony magazine, “He said he needed me to help him. Few husbands tell their wives that they need them after thirty years of marriage, so I gave it up and here I am. Right by his side.”

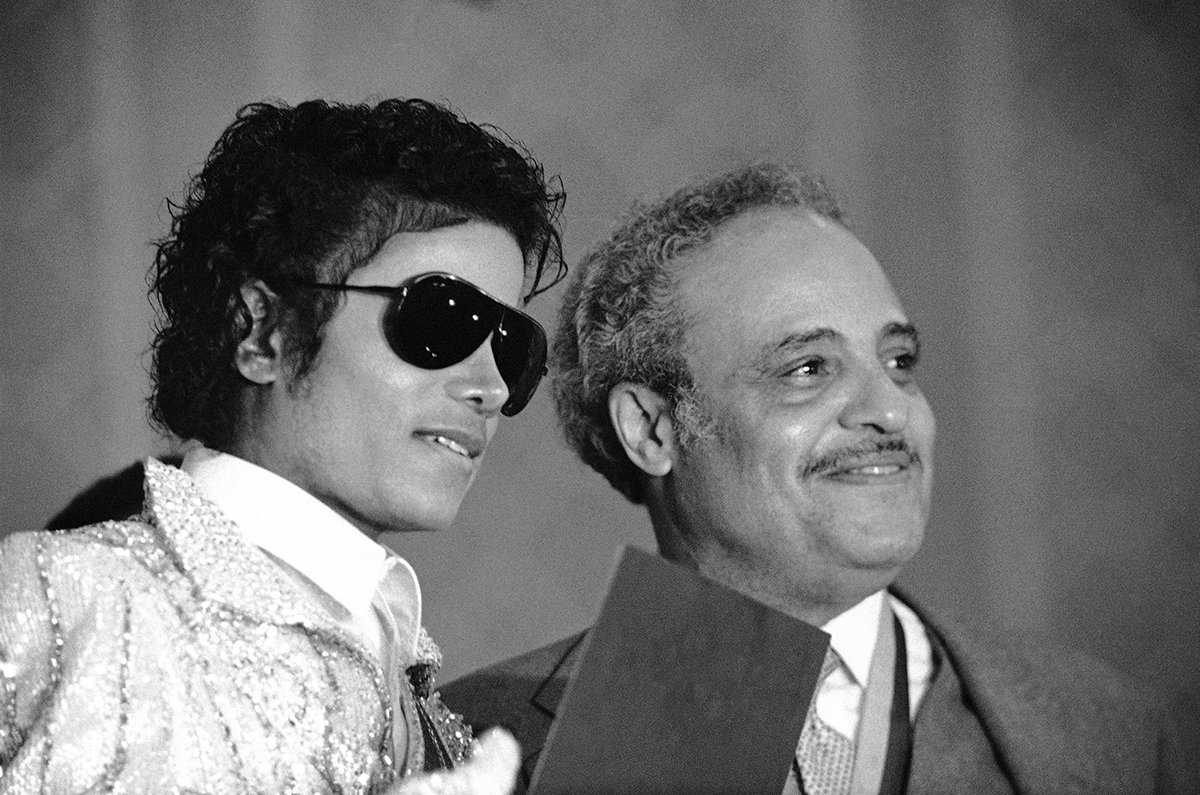

Ben Hooks and Ronald Reagan shaking hands at the White House in 1981. This picture most likely took place weeks before Reagan gave a speech to the NAACP in Denver, CO.

Ben Hooks and Ronald Reagan shaking hands at the White House in 1981. This picture most likely took place weeks before Reagan gave a speech to the NAACP in Denver, CO.

The FCC regulated television and radio stations as well as long-distance telephone, telegraph, and satellite communications systems. Hooks felt that his primary role was to bring a minority point of view to the commission. After noticing that only 3 percent of FCC employees were African Americans, and they were generally in low-paying positions, he encouraged the commission to hire more African American workers at all levels. By the time he left the agency, African Americans made up about 11 percent of the employee population. Hooks also urged public television stations to be more responsive to the needs of African American viewers by treating them fairly in news coverage and including programming directed toward them.

In 1977 Roy Wilkins, who had been the executive director of the NAACP since 1955, retired. The NAACP board of directors wanted an able leader to take his place. They all agreed that Benjamin Hooks was the man. Hooks resigned from the FCC after five years and officially began his directorship on August 1, 1977.

When Hooks took over the organization, its membership had decreased from half a million to just over two hundred thousand. Hooks immediately directed his attention toward rebuilding the base of the association through a membership drive. He also spoke out on behalf of increased employment opportunities for minorities and the complete removal of U.S. businesses from South Africa. He told Ebony magazine, “Black Americans are not defeated.… The civil rights movement is not dead. If anyone thinks we are going to stop agitating, they had better think again.” Hooks’ leadership of the NAACP was marked by internal disputes. He was suspended by the chair of the NAACP‘s board, Margaret Bush Wilson (1919–2009) after she accused him of mismanagement. These charges were never proven. In fact, he was backed by a majority of the sixty-four-member board and continued in the job until retiring in 1993.

Throughout his career, Benjamin Hooks has stressed the idea of self-help among African Americans. He urges wealthy and middle-class African Americans to give time and resources to those who are less fortunate. “It’s time today … to bring it out of the closet. No longer can we provide polite, explicable [easily explained] reasons why black America cannot do more for itself,” he told the 1990 NAACP convention as quoted by the Chicago Tribune. “I challenge black America today—all of us—to set aside our alibis.”

After his retirement, Hooks served as pastor of Middle Baptist Church and president of the National Civil Rights Museum, both in Memphis. He also taught at Memphis University. In July 1998, nearly fifty years after Hooks first began practicing law in Memphis, Tennessee governor Don Sundquist (1936–) asked Hooks, along with four others, to serve on a special state Supreme Court to oversee Tennessee’s election and retention of appellate court judges. (Appellate courts consider appeals or hearings to decide whether an error has been made and the decision of a lesser court should be reversed.)