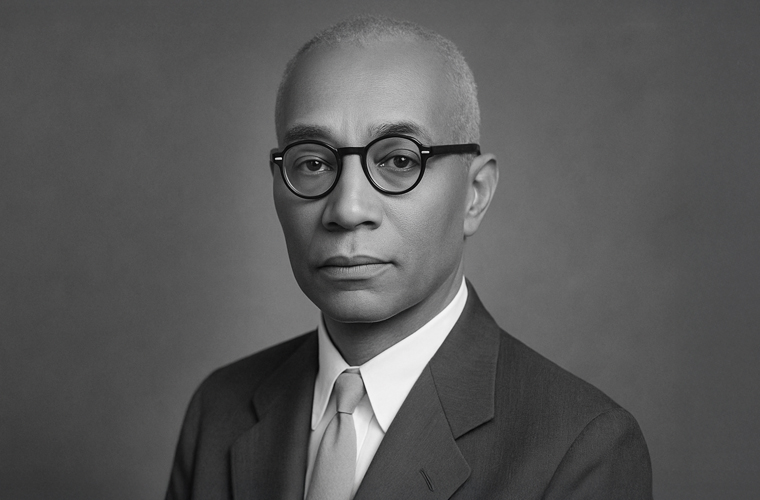

Buck Colbert Franklin, born on May 6, 1879, near Homer in Pickens County, Chickasaw Nation, Indian Territory (now Oklahoma), emerged as a pivotal figure in American legal and civil rights history through his courageous defense of Black residents in the aftermath of the 1921 Tulsa Race Riot. As the seventh of ten children, Franklin grew up in a family marked by resilience, named in honor of his grandfather, a formerly enslaved man who secured freedom for himself and his family. Historical accounts suggest that Franklin’s father, David Franklin, may have escaped slavery during the Civil War, adopting a new name to cement his liberty, a legacy of determination that shaped Buck’s path.

Franklin pursued a legal career in the face of systemic racism, beginning his practice in Ardmore, Oklahoma, a predominantly white town where he encountered significant prejudice. One notable incident occurred in a Louisiana courtroom, where he was silenced solely because of his race. This experience profoundly influenced his decision to focus his legal work on African American communities. Seeking a more supportive environment, he relocated to Rentiesville, Oklahoma, an all-Black town, where he married Mollie Parker Franklin in 1915 and began raising a family. In 1921, Franklin moved his family to Tulsa, settling in the Greenwood District, a thriving Black community known as “Black Wall Street” for its economic prosperity. However, this affluence existed alongside deep racial tensions with the surrounding white population.

The Tulsa Race Riot of 1921, one of the most devastating racial conflicts in U.S. history, erupted in late May following the arrest of Dick Rowland, a young Black man accused of assaulting Sarah Page, a white woman, in an elevator. The incident sparked a confrontation at the Tulsa courthouse between Black and white groups, escalating within 24 hours into a violent riot that left an estimated 300 people dead, primarily Black residents. The Greenwood District was reduced to ruins, with homes and businesses burned, and much of Tulsa’s Black population was detained. Franklin and his family narrowly escaped the destruction, but the aftermath brought further challenges. The Tulsa City Council passed an ordinance prohibiting Black residents from rebuilding, with plans to rezone Greenwood into a commercial district, effectively displacing the community.

Undeterred, Franklin took on the legal fight to protect the rights of Black Tulsans. Leading a challenge against the city’s ordinance, he argued the case before the Oklahoma Supreme Court and secured a landmark victory. This ruling struck down the ordinance, enabling Black residents to begin the arduous process of reconstructing their homes and businesses in Greenwood. Franklin’s triumph was a testament to his legal acumen and commitment to justice, ensuring that the community could reclaim its place as a center of Black resilience and prosperity.

Beyond his legal achievements, Franklin documented his experiences in an autobiography, My Life and an Era: The Autobiography of Buck Colbert Franklin. He continued his legal practice until his death on September 24, 1960, in Oklahoma, though he did not live to see his autobiography’s final publication. His son, John Hope Franklin, a renowned historian and civil rights advocate, played a significant role in completing and publishing the work alongside his son. John Hope Franklin carried forward his father’s legacy, contributing to the landmark Brown v. Board of Education case, which desegregated American schools, and participating in the 1965 Selma-to-Montgomery march for voting rights. Through his legal victories and his family’s continued advocacy, Buck Colbert Franklin left an enduring mark on the fight for racial justice and equality in America.