While Juneteenth is often associated with celebrations of physical emancipations from slavery, it also signaled another type of liberation for the newly freed. Between 1861 and 1900, more than 90 institutions of higher education were founded for Black Americans who could not otherwise attend predominantly white institutions because of segregation laws. These schools and Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) became repositories of African American history and culture, safeguarding generations of memorabilia and documenting the rich culture of HBCU traditions.

For the nearly four million, mostly illiterate and recently freed African Americans, education was a crucial first step, after emancipation, to become self-sufficient. Learning to read was not only desirable, it was oftentimes necessary to protect freedoms, find employment, and communicate with separated family members.

The first schools and colleges for African Americans were created largely through the support of civic and religious organizations, like the Freedmen’s Bureau, the American Missionary Association, and the African Methodist Episcopal Church. In 1890, the Second Morrill Act required states to establish or provide land grants to create separate colleges for Black people if admission to existing institutions was not offered, leading to the expansion of Black colleges and universities throughout Southern states. These institutions became places not only of self-discovery and enlightenment but places that helped define what it meant to have and pursue “freedom.”

Booker T. Washington, the founder of Tuskegee University, described the establishment of the first schools for Black adults and children as an act of “lifting the veil of ignorance” from recently freed communities who sought to receive the education that had been barred from them during slavery and enter into a new class of paid laborers.

Differing Visions

While HBCUs created indispensable opportunities for many, the origins and visions behind their founding reveal a fraught history. Debates over how these schools should be funded and the nature of the education they should provide coincided with their establishment, many of which carried forward into the present. Dr. W.E.B. DuBois, who was born free in Massachusetts, advocated for African Americans to blaze new trails in the arts and sciences and aim for the same status as white professionals. In contrast, Booker T. Washington, who was formerly enslaved, was acutely aware of the terror caused by white mob violence in the South. Washington pushed for African Americans to learn trades that were already available to them, mainly in agricultural and mechanical fields, knowing that attempts to reach a higher status would be met with racist violence.

Education as a Means of Maintaining Racial Hierarchy

In the early 1880s, many industrial philanthropists grew concerned with the future of America’s agricultural economy and subsequently became interested in the education of African Americans. “We cannot afford to lose the Negro,” remarked Andrew Carnegie in an effort to persuade his colleagues to help ensure the new generation of cotton growers would remain largely Black – “We have urgent need of all and of more [Black laborers]. Let us, therefore, turn our efforts to making the best of him.”

We have urgent need of all and of more [Black laborers]. Let us, therefore, turn our efforts to making the best of him. ANDREW CARNEGIE

The General Education Board (GEB), established by John D. Rockefeller Jr., gave a total of $63 million toward African Americans’ education between 1902 and 1960. This sizable donation gave the Board strong financial influence over the educational opportunities for generations of Southern Black people. “White supremacy does not mean hostility to the Negro, but friendship to him,” stated GEB board member J.M.L. Curry. As a means of preserving the racial hierarchy, the philanthropic organization was primarily interested in funding industrial-vocational programs for African Americans to protect a stable, lowermost class of Black farmers and industrial workers.

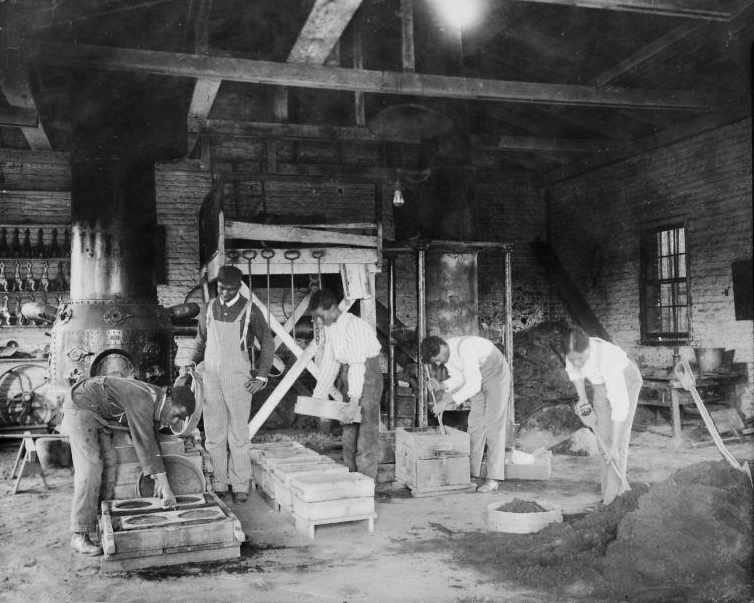

Booker T. Washington was extraordinarily adept at tapping into the mindsets of industrial philanthropists and securing funding for Tuskegee University. Knowing how Carnegie felt about Black labor, Washington promised in his request for a library grant that, “all the work for the building, such as brickmaking, brick masonry, carpentry, blacksmithing, etc., would be done by the students.” As a result, many of the Carnegie-honored libraries at HBCUs were built by students from the ground up with the raw materials donated by the steel tycoon’s foundation. The opportunity to construct a campus library helped many students to practice their trade and earn wages to put toward their tuition payments.

Impact of HBCUs

Despite some of the racist intentions behind the creation of industrial-vocational programs in Southern HBCUs and deliberate attempts to control the livelihood of African Americans, students reaped everything they could from their college experience. Throughout the twentieth century, HBCUs fostered generations of pioneering African American artisans, scholars, and laborers, generating a Black middle class and giving many the skills and connections needed to become leaders in their professional fields. Today, the HBCU tradition remains steeped in the ideology of self-empowerment and community engagement, even decades after formal segregation barring access to historically white institutions was repealed.

HBCUs also housed robust collections of history and culture across the African diaspora. Historically Black College Museums and Archives, through diverse collections of art and craft traditions, oral histories, manuscripts, public records, memorabilia, and detailed documentation, reflect the global significance of an HBCU education.

HBCU History and Culture Access Consortium (HCAC)

NMAAHC’s recently launched HBCU History and Culture Access Consortium (HCAC) has created a partnership with a pilot collaboration of 5 HBCUs: Clark Atlanta University, Florida A&M University, Jackson State University, Texas Southern University, and Tuskegee University. The HCAC is an ongoing collaborative effort to highlight the rich museum and archive collections housed on historically Black campuses through the creation of internship and fellowship programs and a shared digital archive. The initiative will also culminate in a traveling exhibition featuring the collections of the five HBCU partner institutions. You can view the virtual launch of the HCAC here(link is external) and read more about the initiative here.

The need to tell the story of HBCUs, to enrich and diversify the narrative of American education by including underrepresented perspectives, is an ongoing, collaborative effort. The HCAC brings nuance and greater visibility to that struggle, as well as the strength of numbers. While Juneteenth is, in large part, a day to commemorate the suffering of enslaved African Americans and recognize that freedom is still incomplete for many, it also is a day to take a closer look at the people and ideologies that shaped our understanding of what freedom is.