New York Life, the nation’s third-largest life insurance company, opened in Manhattan’s financial district in the spring of 1845. The firm possessed a prime address — 58 Wall Street — and a board of trustees populated by some of the city’s wealthiest merchants, bankers, and railroad magnates.

Sales were sluggish that year. So the company looked south.

There, in Richmond, Va., an enterprising New York Life agent sold more than 30 policies in a single day in February 1846. Soon, advertisements began appearing in newspapers from Wilmington, N.C., to Louisville as the New York-based company encouraged Southerners to buy insurance to protect their most precious commodity: their slaves.

Alive, slaves were among a white man’s most prized assets. Dead, they were considered virtually worthless. Life insurance changed that calculus, allowing slave owners to recoup three-quarters of a slave’s value in the event of an untimely death.

James De Peyster Ogden, New York Life’s first president, would later describe the American system of human bondage as “evil.” But by 1847, insurance policies on slaves accounted for a third of the policies in a firm that would become one of the nation’s Fortune 100 companies.

Georgetown, Harvard, and other universities have drawn national attention to the legacy of slavery this year as they have acknowledged benefiting from the slave trade and grappled with how to make amends. But slavery also generated business for some of the most prominent modern-day corporations, underscoring the ties that many contemporary institutions have to this painful period of history.

Banks absorbed by JPMorgan Chase and Wells Fargo allowed Southerners seeking loans to use their slaves as collateral and took possession of some of them when their owners defaulted.

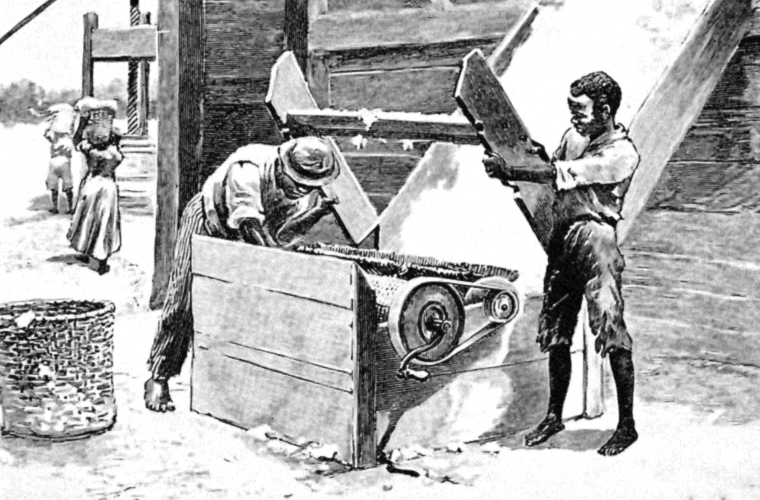

Like New York Life, Aetna and US Life also sold insurance policies to slave owners, particularly those whose laborers engaged in hazardous work in mines, lumber mills, turpentine factories, and steamboats in the industrializing sectors of the South. US Life, a subsidiary of AIG, declined to comment on its slave policy sales. Wachovia, one of Wells Fargo’s predecessor companies, has apologized for its historic ties to slavery as have JPMorgan Chase and Aetna.

More than 40 other firms, mostly based in the South, sold such policies, too, though documentation is scarce, and most closed their doors generations ago.

New York Life survived. Its foray into the slave insurance business did not prove to be lucrative: The company ended up paying out nearly as much in death claims — about $232,000 in today’s dollars — as it received in annual payments. But in the span of about three years, it sold 508 policies, more than Aetna and US Life combined, according to available records.

Now, the descendants of one of those slaves — who were recently identified by The New York Times — are coming to terms with the realization that one of the nation’s biggest insurance companies sold policies on their ancestors and hundreds of other enslaved laborers.

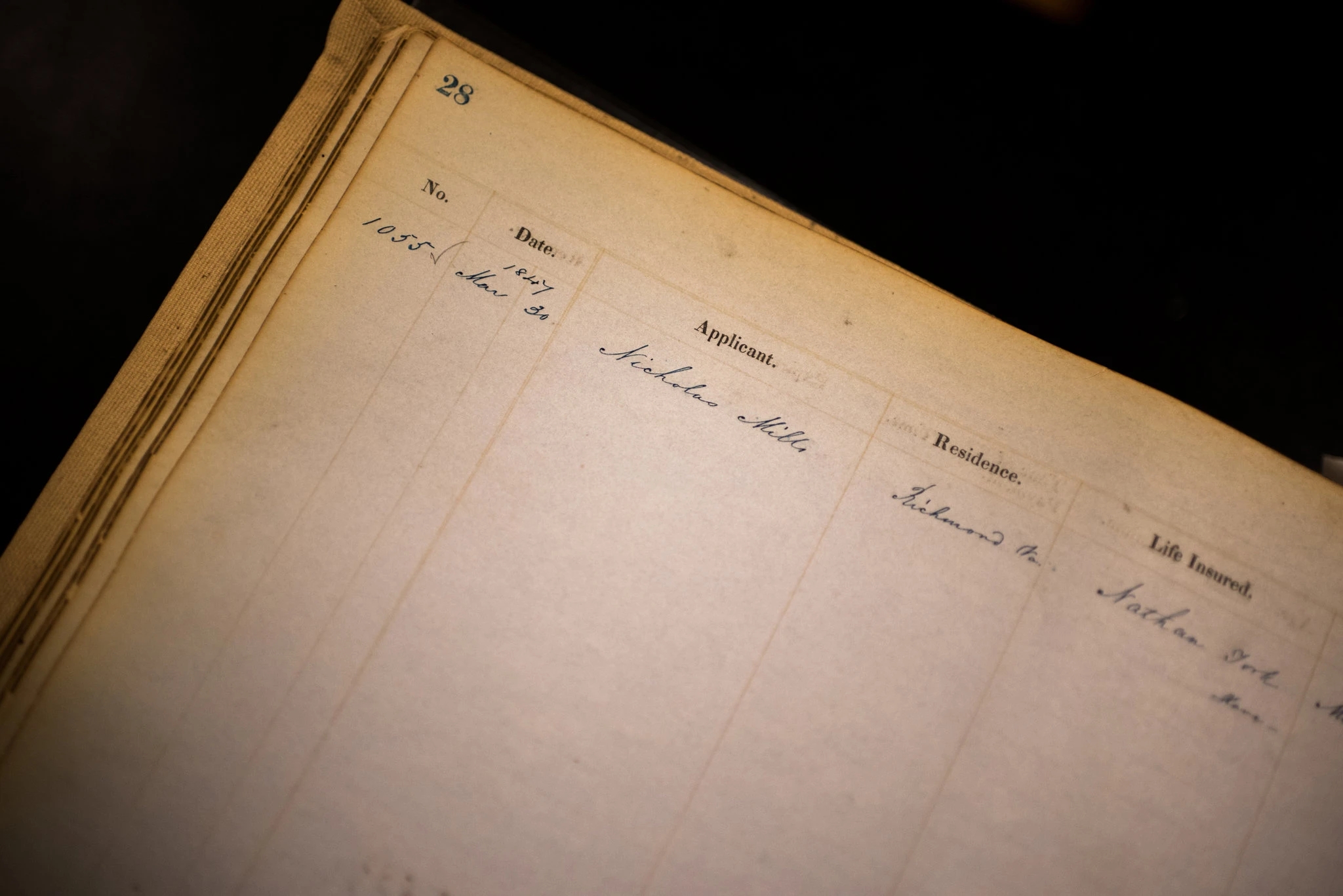

A ledger entry for policy No. 1055 was taken out in 1847 by Nicholas Mills on the life of “Nathan York, Slave.” Mr. York had been insured under a previous policy, No. 447.Credit…Hilary Swift for The New York Times

Policy No. 447 covered Nathan York, a slave who toiled in the Virginia coal mines where the earth often collapsed on its subterranean workforce. Policy No. 1141 insured a slave known as Warwick, who fed the fiery furnaces on a Kentucky steamboat. Policy No. 1150 covered Anthony, who labored amid the whirling blades of a sawmill in North Carolina.

The handwritten record of sales, insurance premiums, and expenditures, many described here for the first time, illuminate the inner workings of a company born before the Civil War. That history has stirred anxiety among some New York Life executives, who take pride in their multiracial workforce and customer base. They worry that news coverage about the company’s ties to slavery may overshadow their efforts to provide philanthropic support to the black community.

New York Life hired one of the insurance industry’s first black agents in 1957. African-Americans currently account for 13 percent of the firm’s employees, including its senior vice president for governmental relations, George Nichols III, who reports directly to the chief executive.

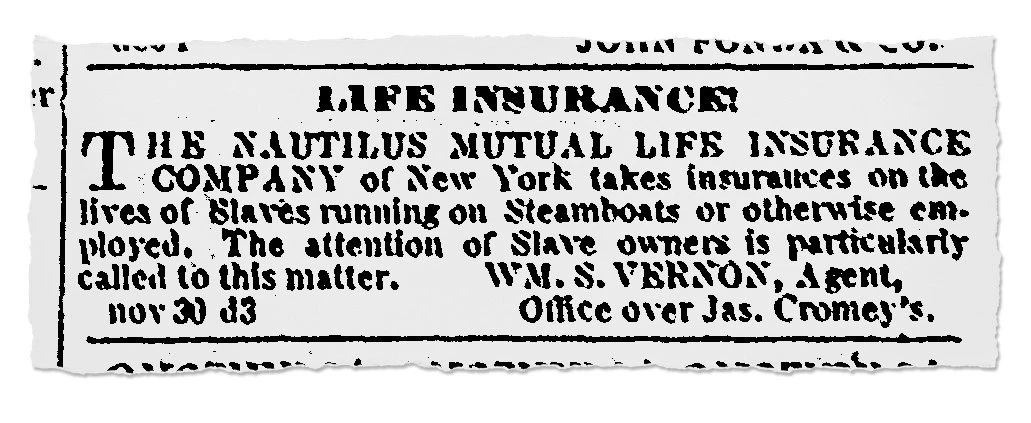

The company donates millions of dollars annually to causes and groups that benefit African-Americans, the executives said, pointing to a $10 million endowment to the Colin Powell Center for Policy Studies at the City College of New York, sponsorship of the National Museum of African American History & Culture and other initiatives. (The company was known as Nautilus Mutual Life Insurance; the name was changed to New York Life in 1849.)

“We profoundly regret that in the 1840s our predecessor company, Nautilus Insurance Company, insured the lives of slaves for a brief period of time,” Kevin Heine, a spokesman for the company, said in a written statement. “While we cannot change our history, our longstanding recognition of it has helped shape our commitment to the African-American community.”

The company’s connections to slavery drew attention in the early 2000s as California and more than a dozen localities, among them Chicago, Philadelphia, and San Francisco began to require companies to disclose their slavery-era activities. The disclosure laws emerged in response to black activists and lawyers who pressed for reparations and a public reckoning with history. (A lawsuit filed against New York Life and other companies tied to slavery was dismissed in 2004 after a judge ruled that the African-American plaintiffs had established no clear link to the businesses they sued and that the statute of limitations had run out more than a century ago.)

New York Life executives found the old records in a storage room that served as an informal archive on the 16th floor of their headquarters, a trove of fraying ledgers and yellowing documents. They turned over the names of slaves and slaveholders as required by law and donated several of the accounting books to the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, where they are available to the public. The company stored the rest in a private corporate archive.

Company officials allowed The Times to review several ledgers from its archive but declined to allow a reporter to interview its archivist to determine whether additional records related to the slave policies still exist. The executives said that slave policies generated only about 5 percent of total revenues during the three fiscal years in which the policies were sold. They said the policies proved to be unprofitable and did not drive the company’s growth.

But historians say the slave policies had an impact on the company’s development. The company had two years to invest or spend much of the revenues from the slave policies before death claims exceeded annual premium payments, according to Dan Bouk, a historian at Colgate University who has studied 19th- and 20th-century insurance companies, and reviewed the company’s figures at the request of The Times.

The policies helped New York Life establish an early foothold in the South, which distinguished it from its larger competitors, said Sharon Ann Murphy, a historian at Providence College. Its agents continued to insure white lives in the region after the slave policies were discontinued.

“Slave policies were an opportunity for them to break into the industry and they actively promoted these policies in the early years,” said Ms. Murphy, who is the author of a book about the emergence of the insurance industry before the Civil War.

“We can be disturbed by this, but we shouldn’t be surprised by it,” she said. “It wasn’t just Southern companies that benefited from slavery; many Northern institutions also benefited directly or indirectly.”

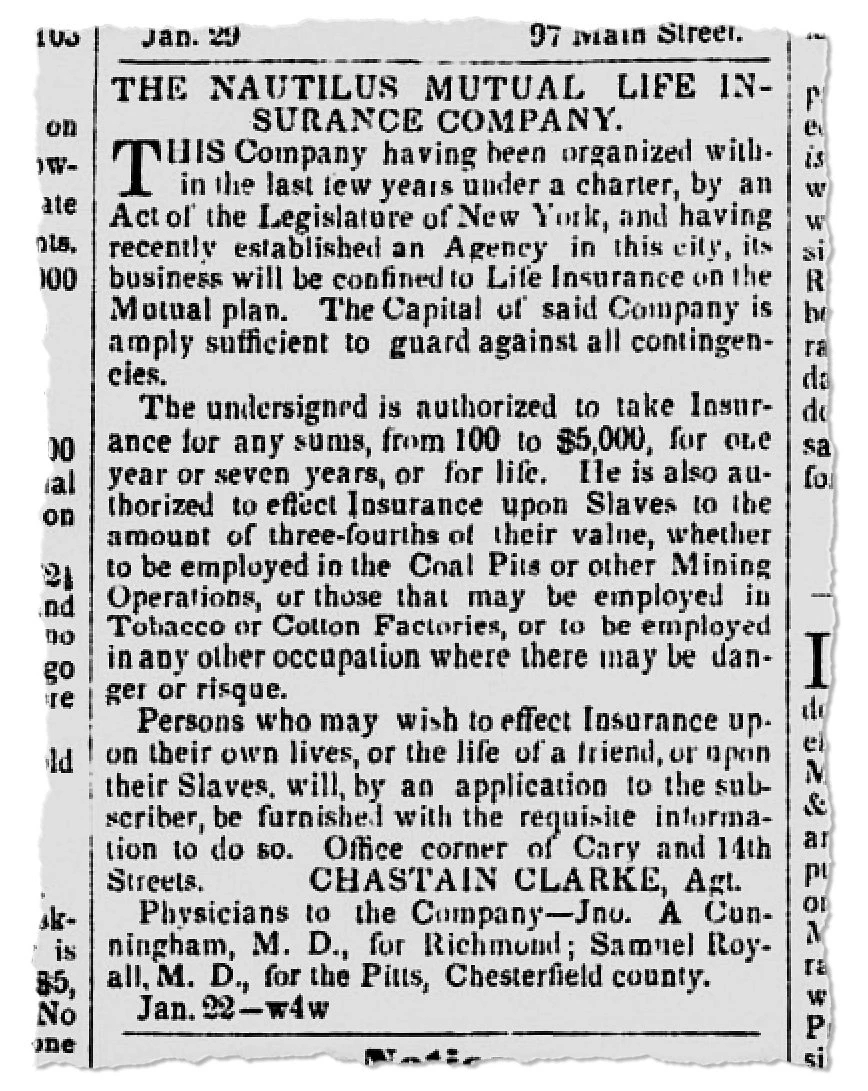

The advertisement appeared in the Richmond Enquirer on Jan. 29, 1846. It described a new firm offering life insurance for slaves employed in any “occupation where there may be a danger or risque.”

Within four days, the customers started streaming into the office of the insurance agent for New York Life. They owned laborers who worked in the coal mines in nearby Chesterfield County and they all knew something about risk.

Their slaves dug for black ore in underground shafts that oozed deadly gases and shuddered with explosions. Dozens of enslaved African-Americans had died in a blast just seven years earlier, mining records show, a catastrophic financial loss for their white owners.

Nicholas Mills, who owned shares in the Midlothian Coal Mining Company, was determined to protect himself from such a calamity. So he purchased policies on more than 20 of his enslaved laborers, including Mr. York, a 40-year-old coal miner and the father of a baby boy.

The premiums Mr. Mills paid in the spring of 1846 — about $7,000 in today’s dollars — flowed into the New York Life office on Wall Street, where employees began recording the names, ages, policy numbers, and occupations of the slaves who were insured.

Slavery was finally abolished in New York in 1827. But the plantations in the South continued to generate business in the city in the decades before the Civil War, according to Eric Foner, a historian at Columbia University.

New York City’s merchants helped to finance the nation’s premier export crop, cotton, and the purchase of the land and slaves needed to grow it. They controlled the boat companies that shipped the cotton to Europe, leading one Southern editor to describe New York City as “almost as dependent upon Southern slavery as Charleston.” And some of these businessmen assumed prominent positions at New York Life.

Mr. De Peyster Ogden, the company’s first president, was a cotton merchant who grew up in a home tended by slaves. He would become a prominent defender of slavery, describing it as an unfortunate, but inextricable part of the nation’s economy.

Several wealthy members of the company’s board also opposed efforts to end slavery, including William H. Aspinwall, a builder of the trans-Panama railroad; Schuyler Livingston, the New York representative of Lloyd’s of London; and James Brown, a banker whose firm, Brown Brothers, controlled several plantations in the South. (A board member, Henry W. Hicks, on the other hand, came from a family of abolitionists.)

It was no surprise then that New York Life tried to tap into the flood of money pouring into the city from the South. In the beginning, the payments from slaveholders and other customers helped the company generate interest and cover the rent of its Wall Street office ($500 for the first year), the salary of its first president ($500), commissions for agents (roughly 5 to 10 percent of premiums), the fees for the medical doctors who examined the slaves ($2 per exam) and office upkeep like painting, carpeting, and postage.

The clothbound ledgers, which describe New York Life’s revenues and expenses in spidery script, also document how the company institutionalized the nation’s racial hierarchy.

Officials typically insured the lives of white customers for $1,000 to $5,000 in the early years. Slaves, on the other hand, were considered property under the law and were typically insured for about $400, the records show, and some for as little as $200.

Payouts from death claims usually went to the grieving relatives of white customers. In the case of slaves, however, it was the slave owners — who insured their laborers and paid the annual premiums — who collected. Abraham S. Wooldridge, a mining magnate and business partner of Mr. Mills, praised the company’s swift response after two of his slaves perished on the job.

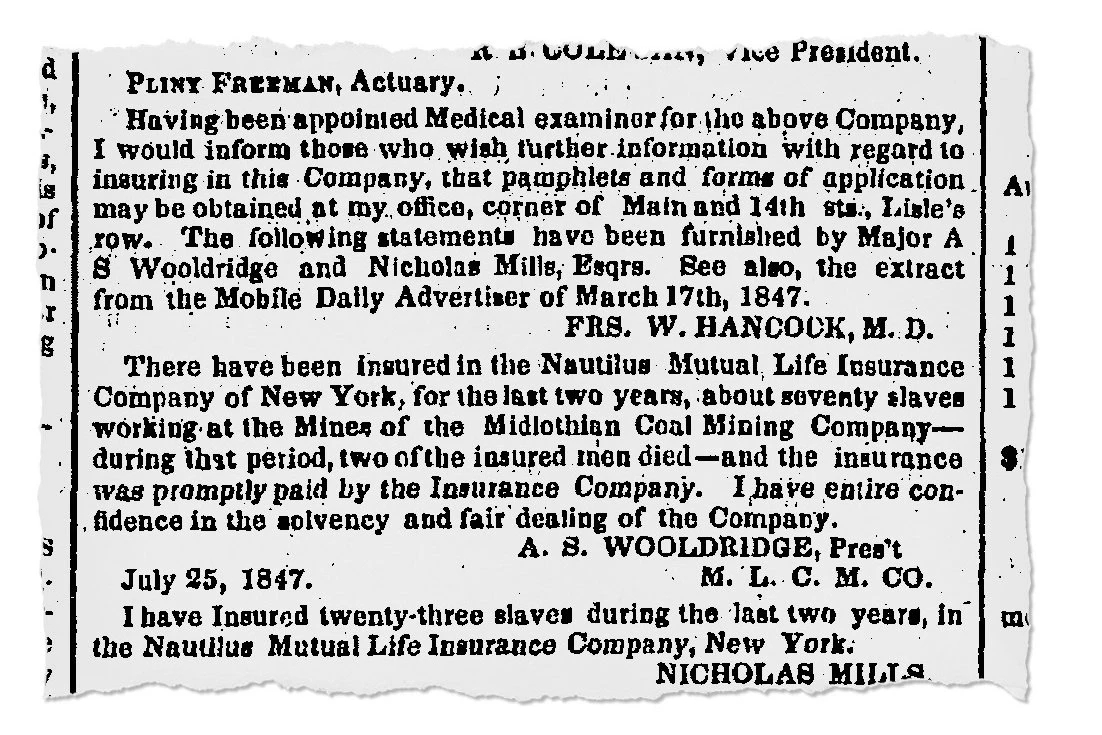

“The insurance was promptly paid,” Mr. Wooldridge said in an advertisement published by the Richmond Whig newspaper in 1847. “I have entire confidence in the solvency and fair dealing of the company.”

Expand image captioned An 1847 ad in the Richmond Whig newspaper contains a testimonial from Abraham S. Wooldridge, who expressed satisfaction that the insurer had paid out on two slaves who died.”>

As the death claims mounted, New York Life’s board voted on April 19, 1848, to discontinue the sale of slave policies. It would take about six years for the last slave policies to lapse.

But the names of the slaves remained inscribed in accounting books that moved from one office to the next as the company grew, handwritten clues that would link the past to the present.

Policy No. 447 led to a red brick church in Midlothian, Va., and to Audrey Mozelle Ross, an amateur historian who has spent years researching the origins of the First Baptist Church. Enslaved miners founded the congregation in 1846, gathering to pray amid the dust and dangers of the coal pits.

Ms. Ross, a retired public health scientist, prayed at First Baptist just as her parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents did before her. She knew the names of the founding members by heart. She never imagined that she was connected to any of them, though, until she received an unexpected email earlier this year. That’s when she learned that The Times, with the help of Crista Cowan, a genealogist at Ancestry, had unearthed a missing piece of her family tree.

Ms. Ross’s great-great-grandfather was Mr. York, a founding member of her church and one of the hundreds of slaves whose lives were insured by New York Life.

“I can’t believe it,” said Ms. Ross, who is 66 and had researched the family histories of several church members, but not her own. “You have just opened my eyes.”

Ms. Ross worked in New York City in the mid-1970s and never dreamed that one of the city’s insurance companies had tried to profit from her ancestor’s enslavement. “I think it was pathetic that they used the labor, the hard work, blood, sweat, and tears of the slaves” to help their business, she said.

Even so, she considers herself lucky. Her great-great-grandfather survived his time as an enslaved miner. After the Civil War, Mr. York continued digging for coal and earned enough money to buy land and cattle. He helped to establish a school for newly freed slaves and became the patriarch of a sprawling family.

Others were less fortunate. The stone ruins of the Grove Shaft building, the remains of the Midlothian Coal Mining Company, are only a short drive from Ms. Ross’s home. Whenever she visits, she prays for the enslaved miners who never made it home.

Godfrey, a 50-year-old slave who was also insured by New York Life, died in a fire in Midlothian on Nov. 20, 1847.

“Burned to death,” reads the entry in the company’s accounting of the dead.

The insurance clerks on Wall Street did not record Godfrey’s last name or the location of his burial place. But they described what happened next: Mr. Mills, Godfrey’s owner, filed a claim with New York Life for the loss of his human property.

Within three months, the company delivered, paying him $337.

The ruins of the Grove Shaft building, part of what was the Midlothian Coal Mining Company in Virginia. At one point, around 70 slaves working at the mine had been insured. Compensation was paid for two who died.

The ruins of the Grove Shaft building, part of what was the Midlothian Coal Mining Company in Virginia. At one point, around 70 slaves working at the mine had been insured. Compensation was paid for two who died.