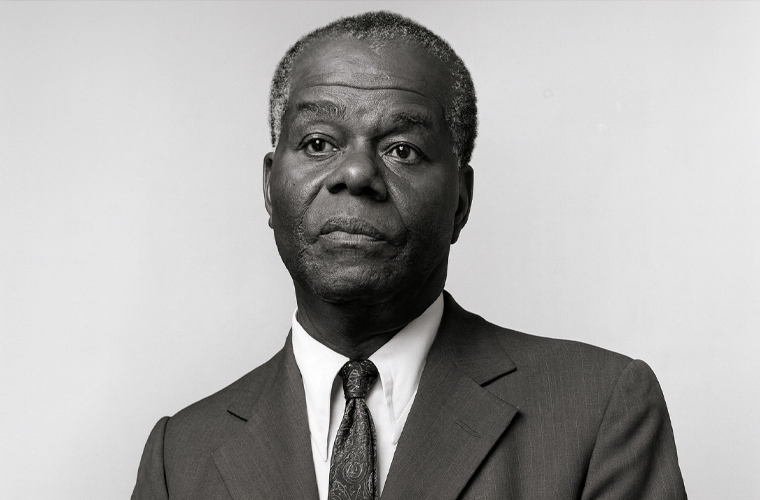

A Pioneer in Africana Studies and Pan-Africanism

John Henrik Clarke, born on January 1, 1915, in Union Springs, Alabama, emerged as a towering figure in African studies, dedicating his life to the exploration and celebration of African and African-American history and culture. Raised on a family farm in Columbus, Georgia, Clarke’s early life was rooted in the rural South, but his journey took him to Harlem, New York, during the Great Migration, a pivotal move that shaped his intellectual and activist pursuits. In Harlem, he found himself at the heart of a vibrant cultural and intellectual scene, immersing himself in the energy of the Harlem Renaissance. Though he lacked a formal education, Clarke’s thirst for knowledge led him to engage deeply with study circles and influential mentors, including the renowned scholar Arturo Alfonso Schomburg, whose collection of African and diasporic materials became a cornerstone for future research. His service as a non-commissioned officer in the United States Army Air Forces during World War II further broadened his worldview, reinforcing his commitment to uncovering and promoting African history.

Clarke’s career was marked by a multifaceted engagement with literature, education, and activism. He co-founded the Harlem Quarterly, a publication that amplified Black voices and perspectives, and later taught at prestigious institutions such as the New School for Social Research and the University of Ghana, where he contributed to the global discourse on African history. His most transformative academic contribution came as the founding chairman of the Department of Black and Puerto Rican Studies at Hunter College, where he worked tirelessly to establish Africana studies as a rigorous and respected academic discipline. This role allowed him to institutionalize the study of African and African-American experiences, creating a framework that empowered future generations of scholars.

During the 1960s, Clarke became a prominent intellectual voice in the Black Power Movement, advocating for a radical reexamination of African history and its contributions to global civilization. His scholarship directly challenged Eurocentric narratives that had long marginalized or distorted African contributions. Through meticulous research and compelling arguments, he sought to correct these historical inaccuracies, emphasizing the richness and complexity of African civilizations. His efforts extended to the publication of numerous scholarly books and anthologies, which became foundational texts in African studies, offering new perspectives and encouraging a broader, more inclusive approach to historical scholarship.

Beyond academia, Clarke’s commitment to advancing Black culture and history was evident in his establishment of key organizations. He founded the African Heritage Studies Association, which fostered collaboration among scholars of African descent, and the Black Academy of Arts and Letters, which promoted artistic and intellectual contributions within the Black community. These initiatives created vital spaces for dialogue, research, and cultural preservation, ensuring that the study of African heritage remained dynamic and accessible.

Clarke’s contributions were widely recognized during his lifetime and beyond. The naming of the John Henrik Clarke Library at Cornell University stands as a testament to his enduring influence, as does the Carter G. Woodson Medallion, awarded to him by the Association for the Study of Afro-American Life and History for his outstanding contributions to African-American scholarship. His work in Pan-Africanism, which emphasized the interconnectedness of African peoples worldwide, continues to resonate with scholars, activists, and communities seeking to understand and honor African heritage.

John Henrik Clarke’s legacy is one of intellectual courage and unwavering dedication. By challenging established historical narratives and advocating for a more inclusive approach to scholarship, he not only reshaped the field of African studies but also inspired countless individuals to engage with the rich tapestry of African history and culture. His life’s work remains a beacon for those committed to truth, justice, and the celebration of African contributions to the world.