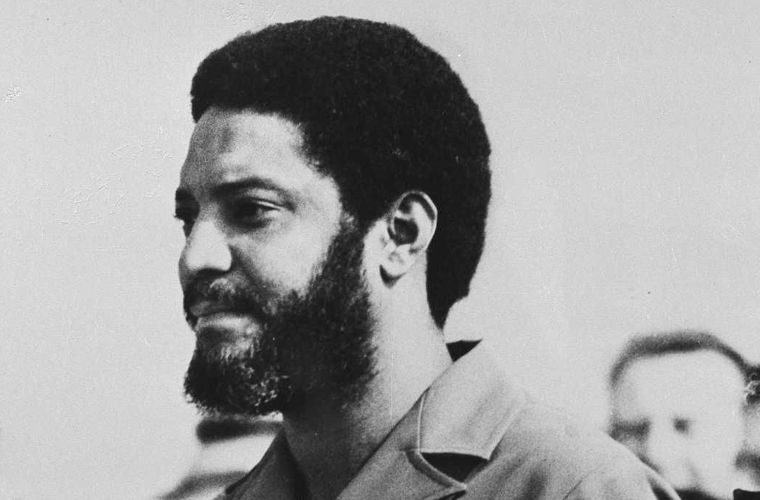

Maurice Bishop was a prominent political figure in Grenada. Born on May 29, 1944, in Aruba, he played a crucial role in the Grenadian Revolution and became the Prime Minister of Grenada from 1979 until his untimely death in 1983. Here is an in-depth look at Maurice Bishop’s life and political career: Maurice Bishop was born in Aruba, which was then part of the Dutch Caribbean. His family moved to Grenada when he was a child, and he grew up in the capital, St. George’s. Bishop received his education in Grenada and later pursued further studies in law in the United Kingdom.

Political Activism and the Grenadian Revolution

Bishop became politically active during his university years in the UK, where he joined left-wing and anti-colonial movements. In 1973, he co-founded the New Jewel Movement (NJM) in Grenada, a socialist political organization aimed at addressing social and economic inequalities in the country. The NJM gained support from various sectors of Grenadian society and emerged as a significant force challenging the ruling government.

Grenadian Revolution and Prime Ministership

On March 13, 1979, the NJM, led by Maurice Bishop, staged a successful coup d’état, overthrowing the government of Sir Eric Gairy. This event marked the beginning of the Grenadian Revolution. Bishop became the head of the new People’s Revolutionary Government (PRG) and assumed the role of Prime Minister.

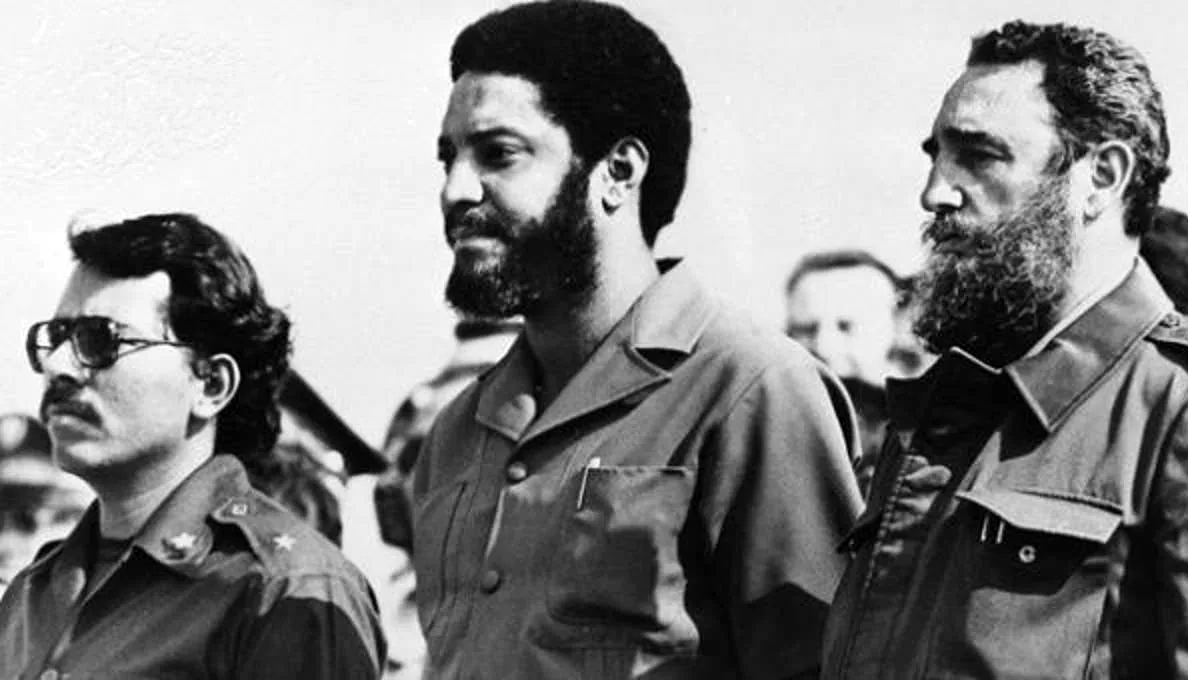

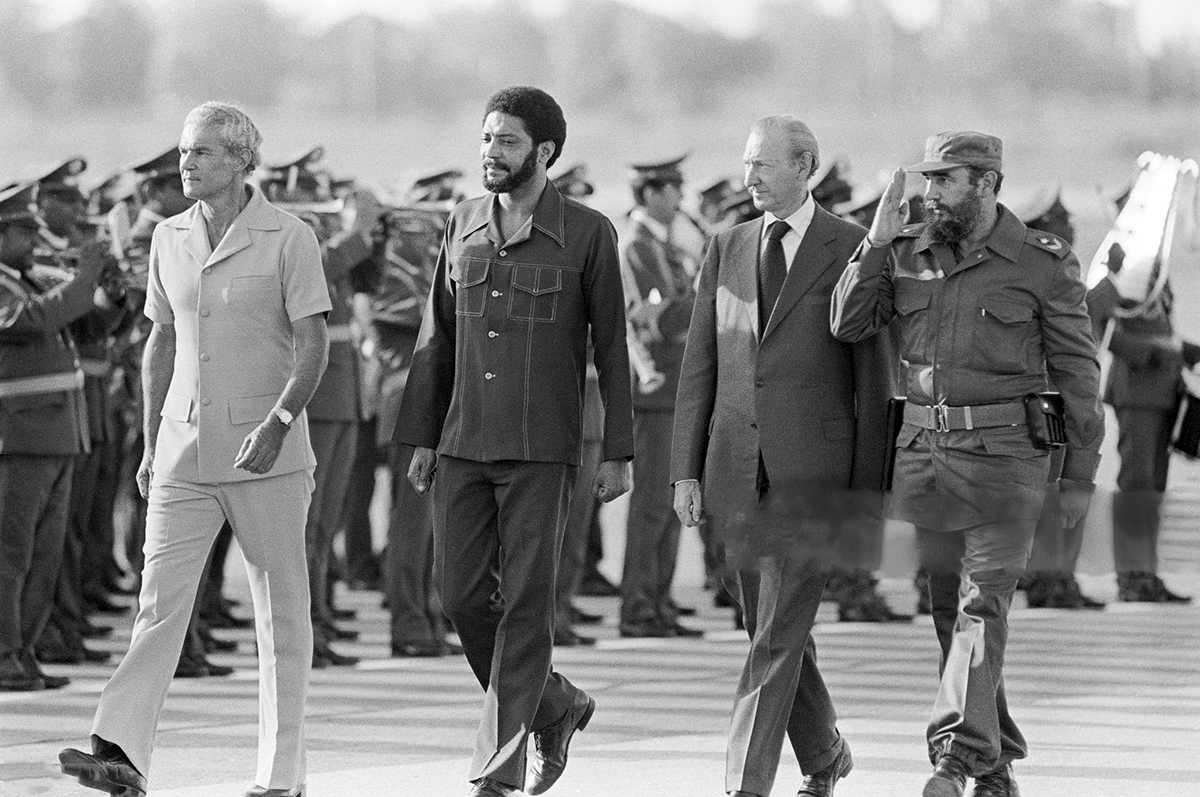

Under Bishop’s leadership, the PRG implemented socialist policies, including land reform, nationalization of industries, and the establishment of cooperatives. The government aimed to prioritize social welfare, education, and healthcare, and reduce economic dependence on foreign powers. Bishop’s government also fostered close relations with other socialist countries, such as Cuba and the Soviet Union.

International Relations and Controversies

Maurice Bishop’s government faced both support and criticism on the international stage. The PRG’s alignment with socialist ideologies and its close relationship with Cuba raised concerns among Western powers, particularly the United States. Tensions escalated between the United States and the PRG, leading to increased scrutiny and political pressure on the Grenadian government.

Tragic End and Aftermath

On October 19, 1983, a power struggle within the People’s Revolutionary Government resulted in Bishop’s arrest by members of his own party. Mass protests erupted in support of Bishop, leading to his release. However, a few days later, on October 25, Bishop, along with several government officials, was executed in a violent coup. The events surrounding Bishop’s death prompted the United States to intervene militarily in Grenada on October 25, 1983. The intervention, known as Operation Urgent Fury, aimed to restore order and overthrow the Revolutionary Military Council that had taken power after Bishop’s death.

Legacy

Maurice Bishop’s legacy remains complex and debated. Supporters regard him as a visionary leader who sought to create a more equitable society in Grenada. They credit his government with implementing social and economic reforms, improving education and healthcare, and promoting regional unity. Bishop is often seen as a symbol of resistance against Western dominance and imperialism. Critics, however, argue that his government’s authoritarian practices, including restrictions on freedom of speech and political dissent, raised concerns about human rights. The manner in which Bishop’s government handled internal conflicts also remains a topic of controversy.

Despite the political controversies surrounding Bishop’s time in power, his influence on Grenadian politics and society cannot be overlooked. The Grenadian Revolution and his leadership marked a significant period of transformation in Grenada’s history. Today, Bishop’s memory is still invoked in political discourse and his impact continues to shape the socio-political landscape