When the Freedom Riders risked their lives in 1961 to protest the segregated bus system in the American south, Moses Newson was there. When the University of Mississippi, a segregated college, admitted its first male Black student in 1962, Moses Newson was there. And when Martin Luther King Jr. was in the midst of planning the Poor People’s March in 1968, Newson again was present to conduct one of the last interviews King would ever live to complete.

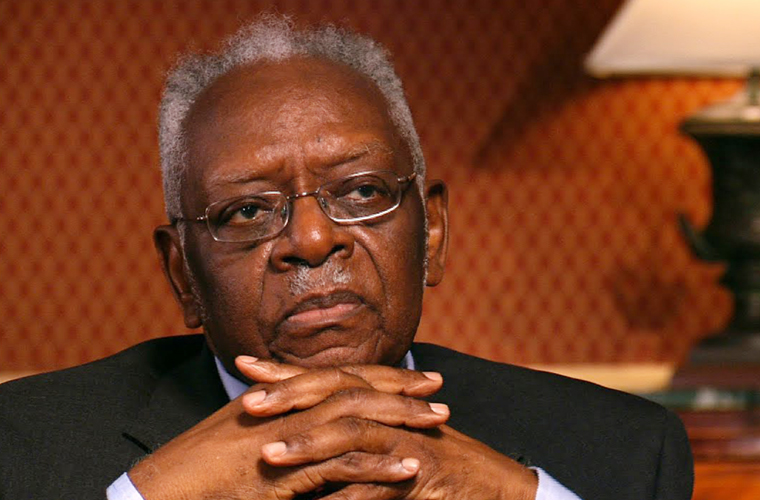

Throughout his 95 years of life, Moses J. Newson used the power of words to move the needle on civil and human rights. From his time as a journalist to his later career with the U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Newson used his writing to convey images and details to anyone who read his work. Born February 5, 1927, in Fruitland Park, Fla., Newson started to read weekly newspapers from a young age. After graduating high school, he enlisted in the US Navy, where he served from 1945 until 1947. This time spent in the Navy afforded him an opportunity to go to college through the G.I. Bill.

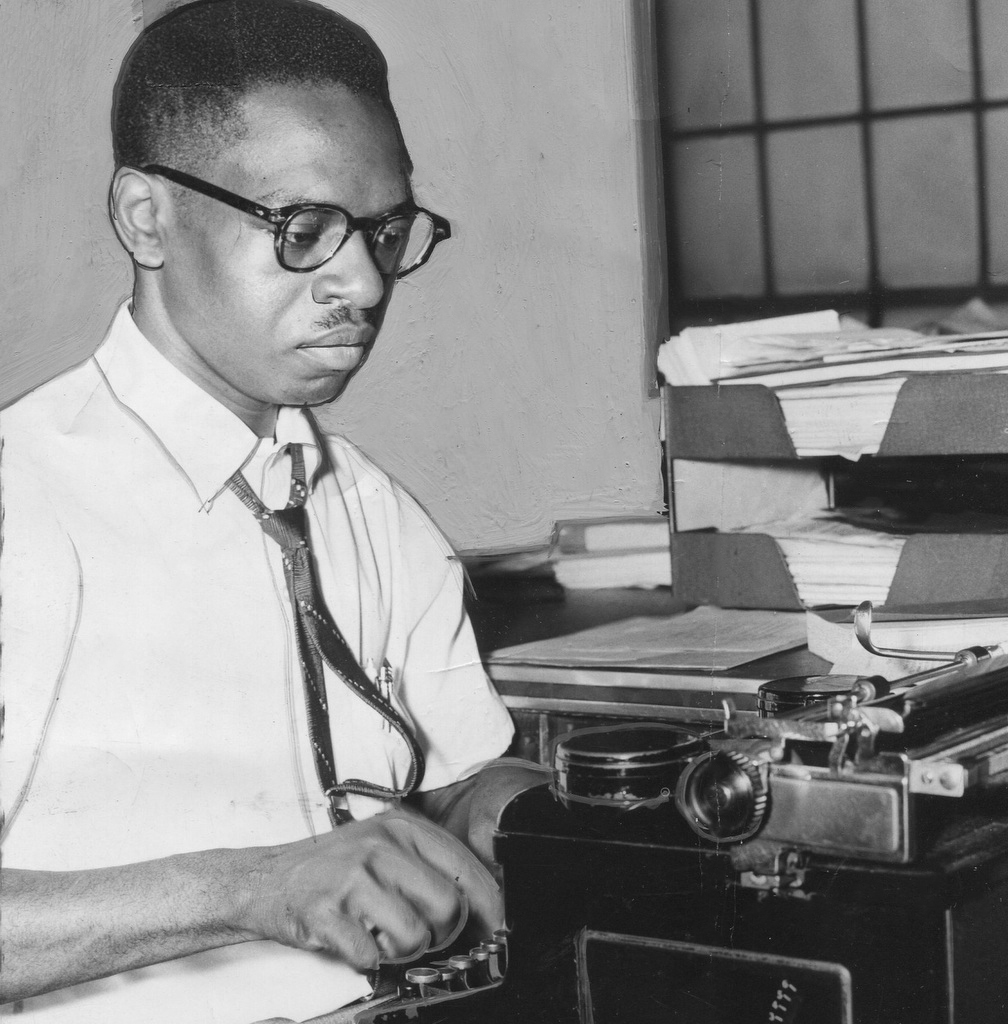

Newson attended Lincoln University in Missouri, where he received his bachelor’s degree in journalism. Following graduation, he got a job at the Tri-State Defender, where he and fellow Lincoln graduate, L. Alex Wilson, were the only two full-time staff members at the paper. While Newson started off there as a reporter, he would later become city editor.

“By observing and reading and watching what other people in the field were doing and accomplishing…that helped me decide that journalism was a good area in which I might be able to make a contribution,” said Newson. In 1955, Newson covered the murder of Emmett Till and the trial of his killers. He relayed what was happening in Mississippi and in racist strongholds across the country with brutal detail.

“When he shares with us, you can get a sense of how deeply that story affected my father as a parent, as a journalist, [and] as a black man who grew up in the South, well-aware of how easily these things can happen to anyone,” said Shawn Newson, the reporter’s youngest daughter. “He would describe the funeral and the pain that so many people felt. I know it must have been painful for my dad too.”

In 1957 Newson left the Defender to join the AFRO. There he would take on the role of reporter and later, city editor. Eventually, Newson became an executive editor for the AFRO, a position he would hold for a decade. For his first assignment, Newson was sent to Little Rock to cover the battle between the Arkansas governor and President Eisenhower over the desegregation of Central High School. During this experience, Newson was kicked out of the courtroom and at one point, attacked by a racist crowd along with other Black journalists.

“A number of us– four or five of us Black guys who were covering that situation–were set upon by people who seem to want to do us a great deal of harm,” he said. “That was one of the more dangerous situations, I think. We just had to run, you know?” Four years later, Newson joined the Freedom Riders who rode from the Baltimore area to New Orleans, a bold act in a land tightly wrapped in Jim Crow’s grip. The trip lasted two weeks. While in Anniston, Ala., Newson and his group were attacked by a mob, and their bus was set on fire. His first-hand account of the experience, first published in May 1961, details how frightening the encounter was for Newson.

“One of the most challenging stories would have been the bus burning story down in Anniston,” he said. “People were attacking the bus. They threw a [firebomb] behind the seats where I was sitting, set the bus on fire, and everybody had to scramble a bit to get out of that situation.” When the University of Mississippi admitted its first Black student, James Meredith, Newson reported on the event and the resulting riots and protests for the AFRO. Although the campus was closed to all Black reporters, Newson did his job from Memphis and continued to provide coverage for the paper.

Newson also had the unique opportunity to interview Martin Luther King Jr. just one month before he was assassinated. King had launched the Poor People’s March campaign in an attempt to convince the government to do more about unemployment and housing issues. The interview took place in Atlanta, where King was at the moment, and discussed a range of topics including the Vietnam War, the civil rights movement, and other major events in history.

Shawn Newson said she often benefited from having a first-hand source to call on when topics that Newsome covered came up. “I had an inside viewpoint because a lot of things that we studied in history, my dad had covered in the news. That was always cool,” she said. In the 1970s, Newson served as a foreign correspondent for several countries in Africa. He covered Nigeria in its post-civil war period, apartheid in South Africa, and the first celebration of independence in the Bahamas. Additionally, he corresponded with Cuba, Panama, and Jamaica during his career.

After 21 years at the AFRO and 26 years as a journalist, Newson took a job in the U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, where he served as a public affairs specialist. “When I first went there, the department covered just about all the major institutions such as social security, health, education, welfare, civil rights,” said Newson.

After 17 years in that position, Newson finally retired at the age of 68.

But just because he was retired does not mean he stopped working. In 1998, he published the book “Fighting For Fairness: The Life Story of Hall of Fame Sportswriter Sam Lacy,” about his friend and AFRO colleague.

“Sam was a very modest guy. He wasn’t too interested in having an autobiography, but I persuaded him to do it,” Newson said. “He was a very, very good journalist, and I guess the short way to put it is he didn’t take any crap out of anybody.” In 2008, Newson was inducted into the MDDC Press Association. Later in 2014, he was inducted into the National Association of Black Journalists Hall of Fame for his coverage of the civil rights movement. Newson continued to write commentary for the AFRO up until 2015 and in 2017 he was still keeping the paper sharp by sending in letters to the editor.