The Deacon Who Ignited Jamaica’s Fight for Justice

In the sweltering heat of colonial Jamaica, where the echoes of emancipation still rang hollow for the formerly enslaved, one man’s voice rose above the oppression. Paul Bogle, a Baptist deacon from the rural hills of Stony Gut, became the fiery catalyst for the Morant Bay Rebellion of 1865—a pivotal uprising that exposed the brutal underbelly of British rule and sparked long-overdue reforms.

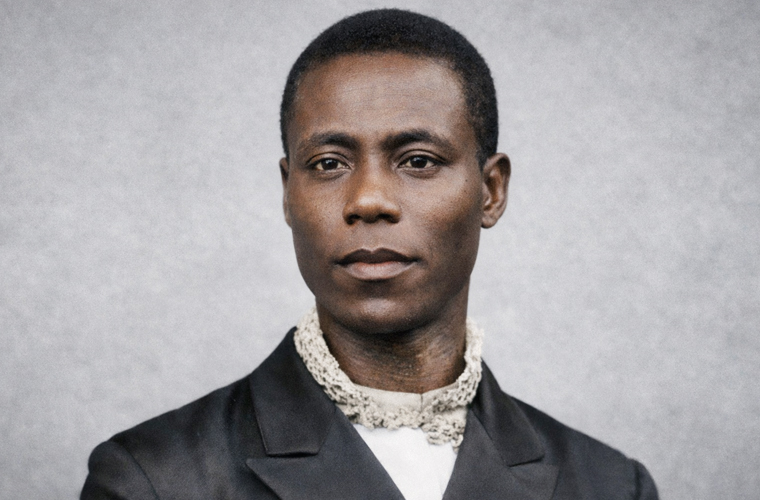

Often depicted in portraits as a stern, resolute figure with piercing eyes and a commanding presence, Bogle embodied the unyielding spirit of resistance against systemic injustice.

Born around 1822 in the remote community of Stony Gut, St. Ann Parish, Paul Bgle grew up in the shadow of slavery’s abolition in 1838. The promise of freedom was short-lived for many Black Jamaicans, who faced grinding poverty, landlessness, and exploitative labor systems under the planter class. Bogle, a farmer by trade, owned a modest plot of land and worked as a sharecropper, but his true calling emerged through faith.

In the 1840s, Bogle joined the Native Baptist Church, a denomination that blended African spiritual traditions with Christianity and often served as a hub for social activism. He rose quickly to become a deacon, using his position to preach not just sermons, but sermons laced with calls for equality and dignity. Described by contemporaries as a “peaceful man who shunned violence,” Bogle drew from the Bible’s teachings on justice, quoting passages like “Let my people go” to rally his congregation against the vestiges of slavery. His charisma and moral authority transformed Stony Gut’s small chapel into a center of political consciousness, where peasants gathered to discuss grievances ranging from unfair wages to biased court verdicts.

By the 1860s, Jamaica was a powder keg. Economic downturns, exacerbated by the American Civil War’s end, left thousands destitute. Black Jamaicans, denied access to education and political power, endured whippings for minor offenses and saw their petitions for land ignored. Bogle, ever the advocate, began petitioning local authorities, forging alliances with reformist figures like George William Gordon, a mixed-race politician who amplified the cries of the rural poor in the Jamaican House of Assembly.

The Seeds of Rebellion: Grievances Ignite

The immediate spark for the Morant Bay Rebellion was a petty injustice on October 7, 1865. Lewis Miller, a Black farmer, was arrested for trespassing while trying to attend a market in Morant Bay, St. Thomas Parish. When locals attempted to free him, violence erupted, and Miller was shot dead by police. This killing, emblematic of the racial bias in the colonial justice system, fueled outrage in Stony Gut, where Bogle had long warned of such abuses.

Bogle, seeing no recourse through legal channels, organized a response rooted in nonviolent protest—at least initially. He penned petitions to Governor Edward John Eyre, decrying the “outrageous” treatment of Black citizens and demanding fair trials, wage protections, and land rights. When these fell on deaf ears, Bogle mobilized his followers, framing the struggle in biblical terms: a modern exodus from Pharaoh’s grip. His leadership was not just tactical but inspirational; as one account notes, he “led a march of hundreds from Stony Gut to Morant Bay, demanding changes due to severe poverty.”

The Morant Bay Uprising: Flames of Defiance

On October 11, 1865, dawn broke over Morant Bay with the rhythmic stomp of approximately 600 protesters—men, women, and children—marching from the hills under Bogle’s command. Armed with sticks, machetes, and a fierce sense of righteousness, they converged on the courthouse, the seat of colonial authority. Their demands were clear: justice for Lewis Miller, an end to arbitrary arrests, and reforms to alleviate famine and inequality.

What began as a peaceful demonstration spiraled into chaos. The local vestry (council) refused to engage, and tensions boiled over when officials fired into the crowd. The protesters, fearing for their lives, stormed the building, killing 18 officials, including the chief magistrate, in a frenzy of retribution. The rebellion spread like wildfire across St. Thomas and neighboring parishes, with disenfranchised peasants torching plantations and clashing with militias. For two weeks, it symbolized a collective roar against 300 years of subjugation.

Governor Eyre responded with draconian force, declaring martial law and unleashing a campaign of terror. Hundreds were flogged, executed without trial, or burned alive in reprisal. Bogle evaded capture for days, leading guerrilla actions from the Blue Mountains, but his luck ran out on October 23 when he was betrayed by a neighbor and seized by Maroon trackers.

Capture, Execution, and the Reckoning

Tried in a hasty court-martial, Bogle refused to beg for mercy, reportedly declaring, “I have committed no crime; I only fought for my rights.” On October 24, 1865, he was hanged in the very Morant Bay square where the rebellion had begun, his body left as a grim warning. In a separate but linked tragedy, Gordon—accused of inciting the unrest—was court-martialed in Kingston, found guilty on flimsy evidence, and hanged on October 23.

Eyre’s brutality drew international condemnation, with figures like John Stuart Mill and Charles Darwin petitioning for his prosecution in Britain. The scandal forced the Crown to dissolve Jamaica’s assembly in 1866, imposing direct rule and enacting reforms: new land laws, expanded courts, and infrastructure investments to address peasant woes. Though the immediate victory was Pyrrhic—over 400 rebels killed—the rebellion marked a turning point, proving that organized resistance could bend the empire’s will.

Paul Bogle’s name is etched into Jamaica’s soul. In 1969, he was posthumously named a National Hero, with his image immortalized on currency and statues in Kingston’s National Heroes Park. His story inspires annual commemorations and fuels discussions on racial justice, echoing in modern movements from Black Lives Matter to Caribbean reparations calls. Bogle wasn’t a revolutionary by temperament but by necessity—a deacon who wielded the Gospel as a sword against tyranny.

Today, as Jamaica grapples with inequality’s remnants, Bogle’s lesson endures: In the face of injustice, silence is complicity, and faith without action is futile. His rebellion wasn’t just a blaze in Morant Bay; it was the spark that lit Jamaica’s path to dignity.