Rufus Andrew Lewis was born on November 30, 1906 (d. 1999), to the late Lula and Jerry Lewis in Montgomery, Alabama. He was the youngest of four children. His sisters, Roberta, Janie, and Corrine preceded him in death. He grew up on the west side of Montgomery and was raised by Mr. & Mrs. Obe Thomas, who were farmers.

His early education was in Montgomery County, where he attended Alabama State Laboratory High School and Alabama State Teachers’ Junior College. He was a graduate of Fisk University, Nashville, Tennessee, where he earned an A. B. Degree in Business Administration in 1931. Lewis taught one year at Conecuh County Training School in Evergreen, Alabama, and one year at People’s Village School in Mt. Meigs, Alabama.

Lewis joined the faculty at Alabama State Teachers’ College, now Alabama State University, in 1933. There he served as an athletic coach and as an assistant librarian. Lewis was promoted to Head Coach for Football and Track in 1934 and was respectfully and affectionately called “Coach Lewis” for his outstanding winning records. While on the faculty, Lewis was a Charter Member of the graduate chapter of Alpha Upsilon Lambda Chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity.

In 1943, Lewis was called to serve in World War II; however, due to an injury sustained from a previous automobile accident, Lewis was ineligible for military/combat service. To demonstrate his patriotism, Lewis worked as a civilian with the National Defense Project for 2 years.

Lewis married Jule Adelaide Clayton in 1935, the daughter of Mr. and Mrs. William and Frazzie Clayton. The Lewis couple had one daughter, Mrs. Eleanor Lewis Dawkins. The young family resided in Patterson Court until they moved into the Clayton Family Home, 801 Bolivar Street, upon the death of William Clayton. Mrs. Jule Clayton Lewis met with a fatal automobile accident in 1958, while en route to a National Negro Business Women’s conference. The home-house is now the residence of the granddaughter, Ms. Karen Dawkins.

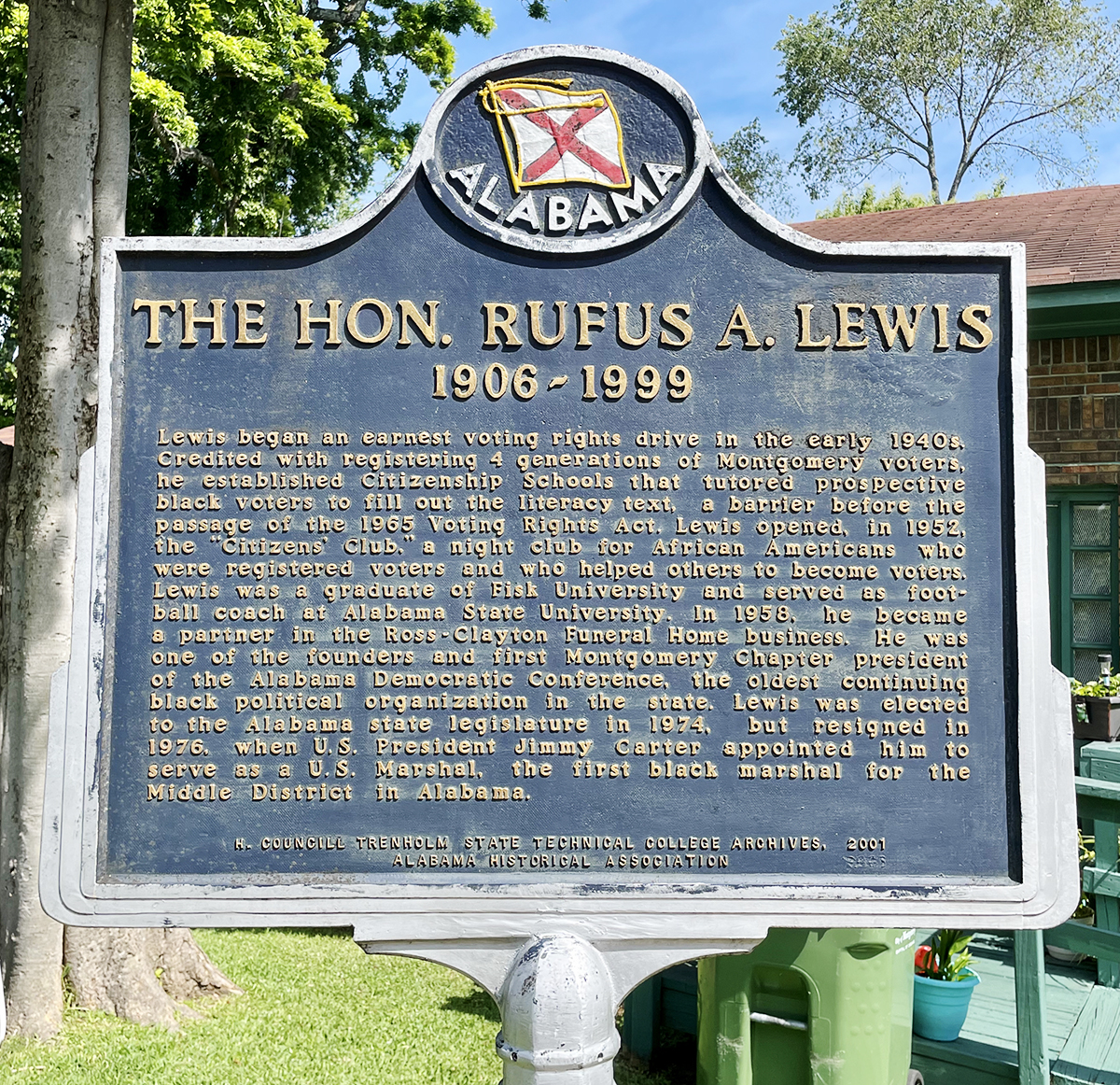

Lewis was always concerned about Black people having the right to vote. The franchise to Lewis was the essence of what it meant to be a first-class citizen. He was especially disturbed that Black people who could read and write and those who fought in World Wars to “save democracy and to make the world safe for democracy” could not obtain the right to vote. When the franchise was continually denied to Black citizens, Lewis launched an earnest and consistent voting rights drive. He worked with students at Alabama State Laboratory High School’s “Citizenship Club” in 1938 and thereafter. By the early “1940s, Rufus Lewis became obsessed with voting rights. An entire generation of Montgomery Blacks says that Lewis…is the reason they first voted.”

Lewis set up “citizenship schools,” especially for veterans, as clinics to teach prospective voters how to fill out the so-called “literacy test,” the pre-requisite to becoming a registered voter. Lewis believed that if a man could go to war and fight for his country, he should be entitled to vote. The Veterans’ Schools were St. Jude and Booker T. Washington High Schools. People from all walks of life attended “citizenship schools” in the homes of people who had been trained by Lewis in “voting clinics.” Lewis was an incredible and detailed organizer. Precision, efficiency, and thoroughness were his calling cards. Indeed, he kept voting registration organizing forms in the trunk of his car, and at every opportunity, he would attempt to get people to join up for citizenship school. He organized neighborhoods block by block, each with a “block captain.”

Already a business associate in his wife’s family business, Ross and Clayton Funeral Home, Lewis opened the “Citizens’ Club” in 1952, a social nightclub where members have registered voters or enrolled in “citizenship schools.”

Lewis was a member of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, now designated as the Historic King Memorial Baptist Church. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., age 26, was a pastor during the early and mid-1950s. Lewis was also a member of Southern Pride Elks Lodge #431, A. A. Peters Masonic Lodge #900, and the National Urban League.

Lewis’s expert organizing skills and his insight into human leadership potential prompted him to nominate Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. to be the spokesman for the Montgomery Improvement Association, the organization that spearheaded the successful Montgomery Bus Boycott. Lewis became Chair of the Transportation Committee that operated with military precision JoAnn Robinson’s The Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Women Who Started It and the Chair of the Voter Registration Committee. He served on the Board and the Executive Committee of the MIA.

His political acumen was awesome. He co-founded the Alabama Democratic Conference, the Black Caucus of the Democratic Party, and was the first president of the Montgomery County Democratic Conference, 2nd Congressional District of the Democratic Conference. He, also, co-founded the East Montgomery Branch of the NAACP and the New Southland Corporation, a group whose purpose was to help save land for Black landowners and to help with the proper utilization and management of that land.

White political candidates curried Rufus’ favor. Rufus through his relentless efforts had harnessed the “Black Bloc” using the strategies of “screening committees” and passing out a “yellow ballot” as a guide for Black voters. “Many Whites think they know Lewis,” said Joe Azbell in an issue of The Montgomery Independent. “But, that’s where they are fooled. Lewis has a poker face when he talks with Whites. He is oriented 100% toward the Black of community,” Azbell continued.

As a result of Lewis’s political prowess, he was appointed to the Montgomery Parks and Recreation Board and served on the Board of Directors of the Montgomery Community Action Committee. He was elected to the Alabama House of Representatives in 1976 and resigned from that position when U.S. President Jimmy Carter appointed him as U.S. Marshal, the first Black ever from the Middle District of Alabama.

Lewis not only had shrewd insight, but also a keen foresight. Lewis predicted after the signing of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, where he was in attendance in the Rose Garden of the White House, by President Lyndon B. Johnson, that Blacks would exercise political muscle and get themselves elected, particularly in local elections. Another foresight is that Lewis lobbied to change the name of Jackson Avenue to that of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Drive. While this has yet to occur, it is a reality that Lewis’ residence address has changed from 801 Bolivar Street to that of Rufus A. Lewis Lane. A public library in Montgomery was named in his honor in 1994.

Lewis in 1974 was elected to the Alabama House of Representatives, District 77. United States President Jimmy Carter appointed Lewis in 1977 to become the first Black U.S. Marshal of the Middle District of Alabama. Lewis’s tenure in this position ended in 1981.

Lewis returned to his life of a business, farming, and cattle-raising. He was still considered the Dean of Black Politics and was sought for advice by both Black and White politicians and political aspirants.

The Honorable Rufus A. Lewis passed on August 19, 1999. He was 92 years old. The Lewis Collection of more than 40,000 papers, manuscripts, and small artifacts is housed in the archives at the H. Councill Trenholm State Community College in Montgomery, Alabama.