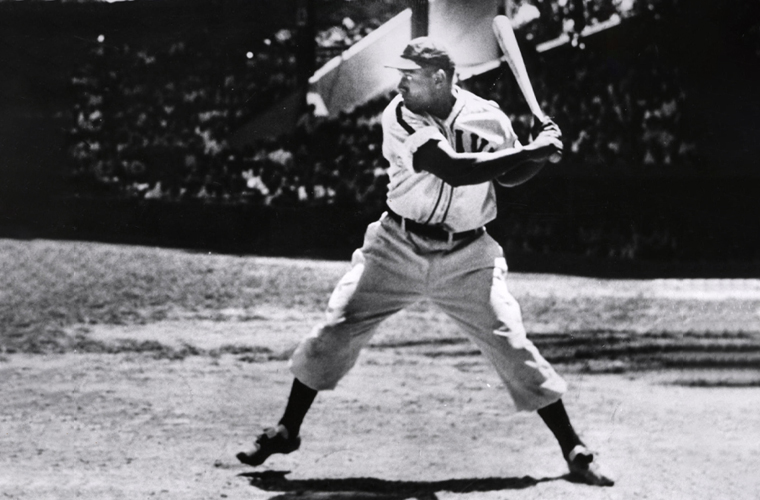

The left-handed half of the Homestead Grays‘ power tandem, Buck Leonard paired with Josh Gibson to lead Cum Posey‘s Grays to nine consecutive Negro National League championships during their halcyon years, 1937-1945. While Gibson was slugging tape-measure home runs, Leonard was hitting screaming line drives both off the walls and over the walls. Trying to sneak a fastball past him was like trying to sneak a sunrise past a rooster. Batting fourth in the lineup of the Grays‘ “murderers’ row,” the muscular pull-hitter displayed a powerful stroke, recording first-half averages of .500 and .480 in 1937-38 and seasonal averages of .363, .372, .275, .265, .327, .290, and .375 for the years 1939-1945. Following the 1943 season, Leonard was credited with averaging 34 home runs per year for the past eight years. Two years later he was selected by Cum Posey as the first baseman on his All-Time All-American team chosen for a national magazine. Posey stated that Leonard was in a class by himself as a fielder and consistently hit over .320.

Possessing a smooth swing at the plate, he was equally smooth in the field. In 1941 one media source described four or five sensational stops that “we’re way beyond the reach of 99 percent of major-league first basemen.” Sure-handed, with a strong and accurate arm, and acknowledged as a smart ballplayer who always made the right play, Buck was a team man all the way. Respected by his teammates, he was even-tempered and professional, and his consistency and dependability were a steadying influence on the Grays. A class guy, he was the best-liked player in the game.

So great were his contributions to the team’s success that even in the years when Gibson was in Mexico, the Grays continued to win pennants. In 1942, with Josh rejoining Buck in the Grays’ lineup, the Grays won their sixth consecutive Negro National League pennant and faced Satchel Paige‘s Kansas City Monarchs in the first Negro World Series between the Negro American League and the Negro National League. The Monarchs had won five of the first six Negro American League flags, and the World Series was a showdown between the two dark dynasties. Leonard was suffering from a broken hand but taped the hand and played in the series. But despite his heroic effort, the Grays lost to the Monarchs in 4 straight games.

After the disappointing Series loss, the Grays rebounded to win back-to-back World Series in 1943-1944 over the Birmingham Black Barons, featuring Leonard’s torrid .500 batting average in the latter series. The home-run duo had finished the regular season tied for the league lead in home runs and followed in 1945 with another one-two finish in that category, with Leonard pounding out a .375 batting average as well, to lead the Grays to another flag.

After a two-year absence from the Negro World Series, the Grays, under Leonard’s inspirational leadership, defeated the Baltimore Elites in the playoffs to cop the final Negro National League flag, then defeated the Black Barons, now featuring a youngster named Willie Mays, in the 1948 World Series to again become champions of black baseball. That year, following batting averages of .322 and .410 the previous two years, Leonard won his third batting title with a .395 average and tied for the league lead in home runs as well. Over a seventeen-year career in the Negro National League, his lifetime stats show a .341 average in league play and a .382 average in exhibition games against major leaguers.

Leonard was born in Rocky Mount, North Carolina, the oldest son in a family of six children. His father, John Leonard, was a railroad fireman, and his mother, Emma, was a housewife. His parents called him “Buddy,” but when his younger brother Charlie was small, his efforts to pronounce the name resulted in “Buck,” hence the nickname by which he is known. He enrolled in Lincoln Elementary School in 1913 and attended through the eighth grade. When his father died from the influenza epidemic in 1919, he had to help support the family by working after school in a hosiery mill and shining shoes at the railway station. When he turned sixteen, he began working full-time at the Atlantic Coastline Railroad Shop, putting brake cylinders on boxcars.

His first interest in baseball came from watching the white Rocky Mount minor league ballclub, whose ballpark was near his home. Later he became a batboy for the local black semi-pro team. Later, while working at the railroad shop, he began playing semi-pro baseball, and for seven years he worked a full-time job and was a star on his hometown baseball team. But in 1933 the Depression required a cutback at the railroad shop and Leonard was forced by the Depression to leave home to pursue a professional baseball career.

That season he played successively for the Portsmouth Firefighters, the Baltimore Stars, and the Brooklyn Royal Giants, where he played in the outfield. Smokey Joe Williams saw him playing with the Royals and connected him with the Homestead Grays for the 1934 season, and Leonard remained with the Grays through the 1950 season.

During his tenure in the Grays‘ flannels, he quickly gained the respect and appreciation of inside baseball men. He was also a favorite of the fans and became a fixture in the annual East-West All-Star classic. As usual, in 1948 Leonard was selected to the East squad’s starting lineup, marking his eleventh year, an All-Star record. His first appearance came in 1935, in the middle of a .338 season, when he entered the game as a pinch hitter. His first starting assignment in an All-Star game was two years later when he batted cleanup and counted a homer in his pair of hits as he powered the East to a 7-3 victory over the West squad. That began a skein of five straight starting assignments in the East-West classic, culminating in another homer among his pair of hits in the 8-3 victory in the 1941 contest. After missing the 1942 game due to an injury, he banged out another homer in 1943 classic to establish an All-Star record while also compiling a lifetime .317 average in this star-studded competition.

When he was in his prime, he and Josh Gibson were called into Clark Griffith’s office and asked if they were interested in playing in the major leagues. Although they responded affirmatively, nothing came of the meeting, and it was eight years before Jackie Robinson was signed and the door finally opened for blacks in the major leagues. In 1952, when Bill Veeck offered him a chance to play with the St. Louis Browns, the veteran slugger’s age was against him, and he knew the opportunity had come too late. After the demise of the Negro National League following the 1948 season, he continued with the Grays for another two years, playing against a lesser caliber of competition, until the Grays folded following the 1950 season.

Being accustomed to Latin American climates from when he had played in Cuba (Mananao in 1948-1949), Puerto Rico (Mayaquez in 1940-1941), and Venezuela (Caracas in 1945-1946 on an American All-Star team), he signed to play in the Mexican League, registering averages of .325 and .328 for the 1951-1952 seasons with Torreon. The respect that his powerful bat commanded is apparent in the number of free passes he was issued, averaging more than a walk per game and almost one-fourth of his plate appearances. His winters in Cuba yielded a lifetime .284 batting average. During his winter in Puerto Rico, he had compiled some impressive credentials, including a .389 batting average with 8 homers in only 118 at-bats, yielding 1 homer per 14.8 at-bats and one extra-base hit per 4.7 at-bats.

In 1953 he returned to his home in Rocky Mount, North Carolina, but was prevailed upon to finish the season with the Portsmouth team in the Piedmont League, where he hit .333 in 10 games. Two years later, at age forty-eight, he slammed 13 home runs in 62 games while hitting .312 with Durango in the Central Mexican League to close out a twenty-three-year career in baseball.

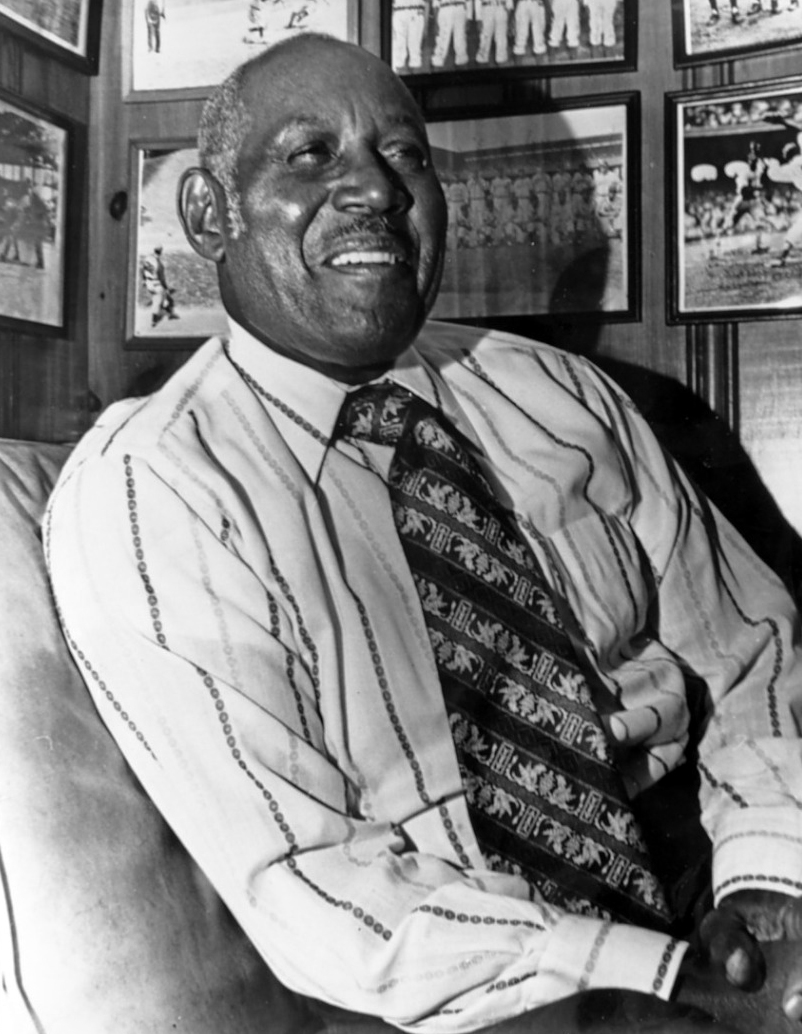

After retiring from baseball he worked as a truant officer with the Rocky Mount school system, operated his own reality agency, and was an officer with the Rocky Mountain baseball team in the Carolina League.

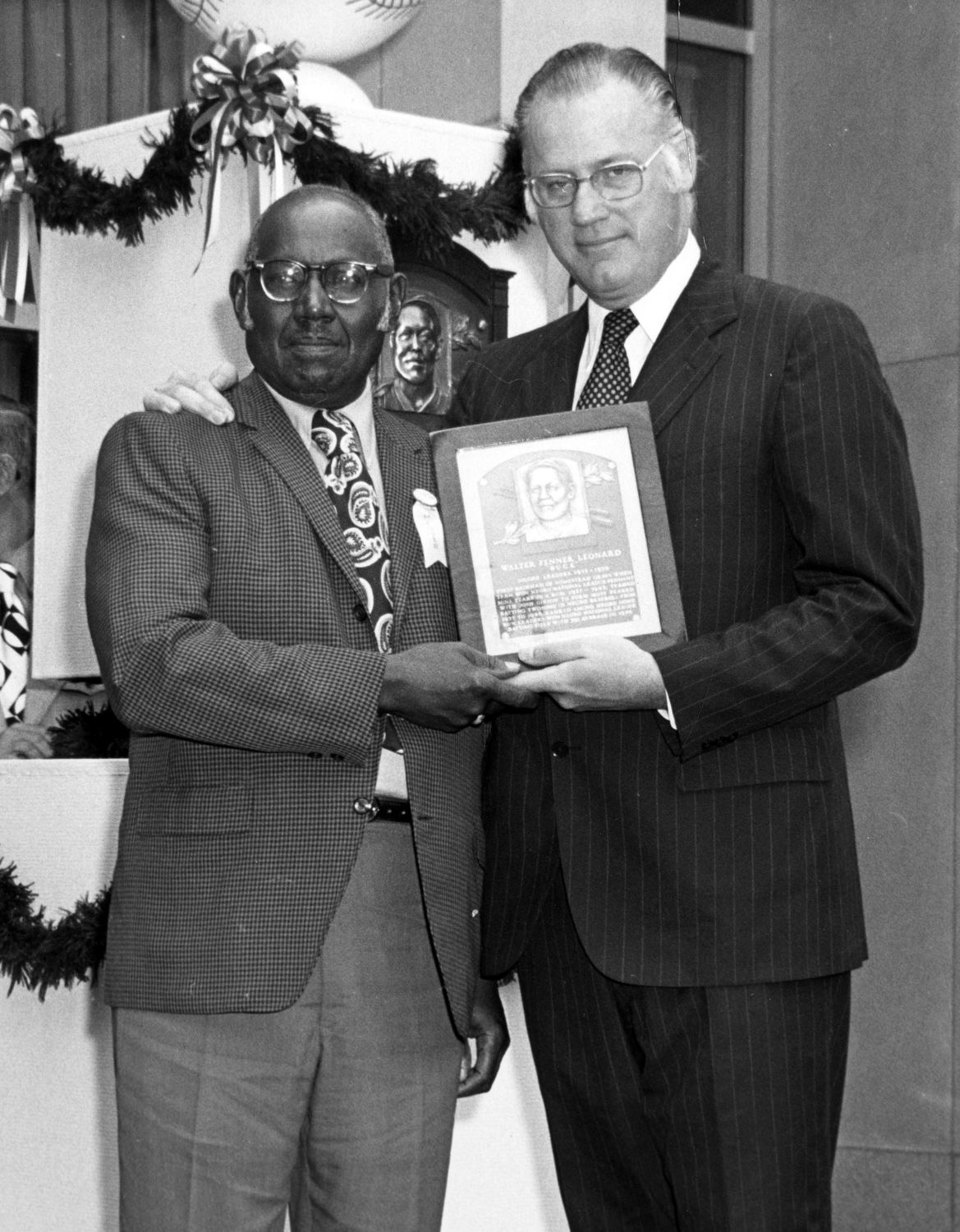

Fortunately, although national recognition of his great talent also came late, Buck Leonard was still able to smell the roses when he was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame along with Josh Gibson in 1972. Called the “Black Lou Gehrig,” he showed the same skill on the diamond and the same strength of character off the field.