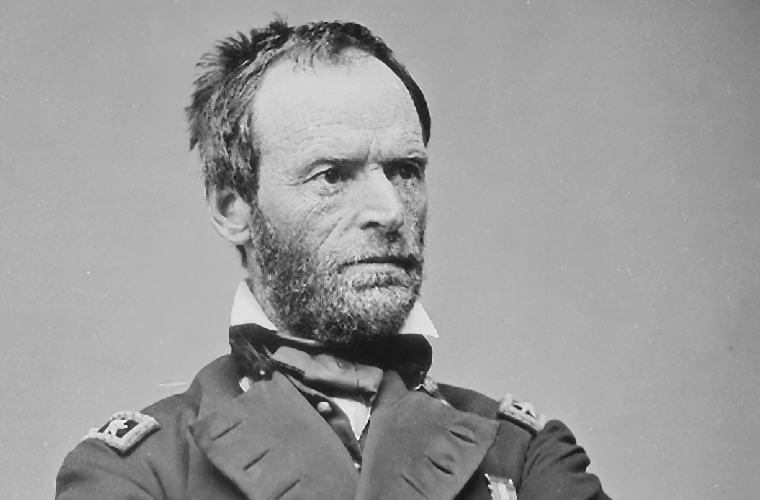

William Tecumseh Sherman was a Union general during the Civil War, playing a crucial role in the victory over the Confederate States and becoming one of the most famous military leaders in U.S. history. The logistical brilliance on fiery display during Sherman’s March to the Sea from Atlanta to Savannah, Georgia, then north into the Carolinas, helped end the bloody war. But the devastation wrought by Sherman’s March remains controversial, with Sherman still loathed by many Southerners today.

Sherman’s Early Years

With an unusual middle name received from his father, a prominent lawyer, and judge who admired the Shawnee chief Tecumseh, William Tecumseh Sherman was born February 8, 1820, in Lancaster, Ohio. The death of Sherman’s father when he was 9 left his mother a poor widow with 11 children. Most of the Sherman children were fostered out to live with other families. Sherman, nicknamed “Cump,” was raised by John Ewing, a family friend who was an Ohio senator and Cabinet member. Sherman later married his foster sister, Ellen Ewing, and the couple had eight children.

Sherman was not the only successful member of his family. An elder brother became a federal judge, and a younger brother John Sherman was elected to the U.S. Senate and later served as both secretary of the treasury and secretary of state. Several of his Ewing foster siblings also rose to prominence.

West Point and Early Military Career

When Sherman was 16, John Ewing secured him a position at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. There he met and befriended several future military leaders who he would fight alongside – and against – during the Civil War. Sherman graduated in 1840 and ranked sixth in his class. He excelled in the academic side of his training but was dismissive of West Point’s strict set of rules and demerits, a trait he would carry with him throughout his military career. He was stationed in Georgia and South Carolina and fought in the Second Seminole War in Florida. This first introduction to life in the South left a lasting favorable impression.

Unlike many of his West Point classmates, Sherman did not see action in the Mexican-American War. Instead, he was stationed in Northern California, which was just on the verge of the California Gold Rush. He spent several years there as an administrative officer, eventually rising to the rank of captain. But with little combat experience, Sherman realized future advancement was unlikely. He resigned from his commission in 1853 but remained in California with his growing family.

Sherman Before the Civil War

Sherman became a banker but was overwhelmed by the frenetic pace of San Francisco, a city teeming with an influx of speculators. Sherman’s bank failed in 1857, and he briefly moved to Kansas, where he practiced law. Sherman returned to the South in 1859, when he accepted a position as superintendent of the Louisiana State Seminary of Learning and Military Academy (now Louisiana State University). He was a popular headmaster and was very fond of the friends he made there. Sherman was not an ardent opponent of slavery, but he was vehemently against the idea of Southern secession over the issue. He repeatedly warned his Southern friends of the dangers they faced taking on the more prosperous, industrialized North, but to no avail. He resigned his position after Louisiana seceded in January 1861.

For several months, he worked as the president of a St. Louis streetcar company. After the Confederate States of America attacked Fort Sumter, Sherman worried that President Abraham Lincoln was not committing enough troops to bring the war to a swift end. But he overcame his doubts, and his brother John secured him a commission in the U.S. Army.

First Battle of Bull Run

Sherman became colonel of the new 13th Infantry Regiment. Before that unit was fully activated, he led a brigade at the First Battle of Bull Run in July 1861. The Union suffered a surprising defeat, but Sherman was praised for his actions, and Lincoln promoted him to brigadier general of volunteers. Sherman’s fears about the war escalated when he was transferred to Kentucky and the Army of the Cumberland. Sherman succeeded General Robert Anderson but suffered grave doubts about his lack of men and supplies, as well as his own abilities.

Sherman called for 200,000 men and was widely ridiculed in the press, some of which called him insane, an event that permanently soured Sherman on the media. In November 1861, Sherman was relieved of his duties and returned home to Ohio, suffering from depression and a nervous breakdown.

Sherman and Grant

He returned to service just weeks later, again assigned to the Western Theater. He supported Ulysses S. Grant at the successful Battle of Fort Donelson, Kentucky, and the two began to develop a close bond. Now serving under Grant in the Army of West Tennessee, Sherman fought at the Battle of Shiloh in April 1862. Caught unprepared by the Confederate assault (he had dismissed intelligence reports on the size and placement of enemy troops), he rallied his troops for an organized retreat that prevented a rout, allowing Union forces to secure victory the following day.

He was promoted to major general of volunteers. Grant was heavily criticized for the losses at Shiloh and considered resigning, but Sherman convinced him to stay. Sherman continued to serve with Grant in the West, culminating in the capture of the vital Confederate stronghold after the Siege of Vicksburg, Mississippi. Despite misgivings over Grant’s unorthodox campaign and siege, which earned Grant more criticism (this time over his drinking), Sherman provided key logistical support. When the city finally fell on July 4, 1863, the Union gained control of the Mississippi River, a key turning point in the war.

President Lincoln recognized the value of both men: Grant was put in charge of all troops in the West, and Sherman received an additional commission as brigadier general of the regular army. At the head of the Army of Tennessee, Sherman was criticized for his performance at the Battle of Chattanooga, although the Union eventually prevailed. He assumed control of all Western armies when Grant was transferred East to take command of all Union armies.

Sherman Takes Atlanta

In May 1864, Sherman set out for Atlanta, a center of Confederate industry. Sherman’s troops were on the move for four months, as he squared off against Confederate Generals Joseph E. Johnston and John B. Hood. Hood was forced to abandon the city, and Sherman captured Atlanta in early September. The city was nearly destroyed, although it is still debated whether the worst of the damage was done by Sherman’s men or retreating Confederate troops. With Grant suffering devastating casualties in the East (while winning militarily), Sherman’s victory in Atlanta helped Abraham Lincoln secure reelection to a second term.

By this time, Sherman was convinced that the Confederacy could only be brought to heel by the complete destruction of both its military and civilian ability to wage war. Despite his earlier fondness for the South and its people, his strategy of “total war” would bring devastation to the region, earning Sherman a deep level of hatred (some of which remains today). Sherman himself loathed the impact of the fighting, but realized its necessity, famously saying, “War is cruelty. There is no use trying to reform it. The crueler it is, the sooner it will be over.”

Sherman’s March to the Sea

With the full support of both Lincoln and Grant, Sherman devised an unusual plan. In November 1864, he departed Atlanta with 60,000 troops, bound for the coastal port of Savannah. He separated his men into two Corps, which tore through the countryside, destroying both military and civilian targets. Twisted railroad lines along the way became known as “Sherman’s neckties.” Georgia’s citizens lived in fear of advancing troops, but the rest of the country had no news of Sherman’s March to the Sea. His distrust of the press led Sherman to ban reporters, and many Americans had no clue where the army went after leaving Atlanta.

Sherman’s March to the Sea showcased his logistical brilliance. Marching in secret meant he had no connection to Union supplies, forcing his men to carry with them everything they would need. They foraged and stole food to supplement rations, and built pontoon bridges and roads to traverse the terrain. Finally, in December, Sherman’s troops showed up outside Savannah, which they easily occupied. Sherman wired the president on December 22, offering Lincoln the city as a Christmas gift.

Early in the new year, Sherman turned his attention north, marching his men through the Carolinas. South Carolina was treated perhaps even harsher than Georgia – the first state to secede was also the state where the Confederacy first fired shots on federal Fort Sumter. Most of the city of Columbia was burned to the ground. By the spring, Sherman’s army was in North Carolina, when news spread of Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox.

Sherman’s Post-Civil War Career

Sherman remained in the U.S. Army after the war. When Grant became president in 1869, Sherman assumed command of all U.S. forces. He was criticized for the role he played in America’s war on Native Americans in the West, but he himself was critical of the U.S. mistreatment of the native population. He retired from active duty in 1884, eventually settling in New York. He brushed aside repeated requests to run for political office, saying, “I will not accept if nominated, and will not serve if elected.”

Sherman died in New York on February 14, 1891, at age 71, and was buried in St. Louis. In a final tribute from a former foe, Joseph E. Johnston served as a pallbearer at Sherman’s funeral. Refusing to don a hat as a sign of respect, Johnston caught a cold, which developed into pneumonia, and died just weeks later.