A bright girl, Rebecca attended a prestigious private school, the West-Newton English and Classical School in Massachusetts, as a “special student.” In 1852, she moved to Charlestown, Massachusetts, and worked as a nurse. In 1860, she took the bold step of applying to medical school and was accepted into the New England Female Medical College.

The New England Female Medical College was based in Boston and attached to the New England Hospital for Women and Children. It was founded by Drs. Israel Tisdale Talbot and Samuel Gregory in 1848 and accepted its first class, of 12 women, in 1850. From its inception, many male physicians derided the institution, complaining that women lacked the physical strength to practice medicine; others insisted that not only were women incapable of mastering a medical curriculum and that many of the topics taught were inappropriate for their “sensitive and delicate nature.”

Fortunately, Drs. Talbot and Gregory ignored such false claims and organized a school that required “a good English education,” a “thesis on some medical subject,” and a set of courses on the theory and practice of medicine, materia medica, chemistry and therapeutics, anatomy, medical jurisprudence, obstetrics and diseases of women and children, and physiology and hygiene. The coursework was 17 weeks in length (30 or more hours per week) during the first year of instruction. Following this was a two-year preceptorship, or apprenticeship, under an established physician’s supervision.

In 1864, Rebecca became the New England Female Medical College’s only African-American graduate (the school closed its doors in 1873.) A few statistics help put her remarkable achievement in perspective. In 1860, there were only 300 women out of 54,543 physicians in the United States and none of them were African-American. Some historians have wondered if Rebecca even knew of her status as “the first” given that for many decades in the 20th century that credit was awarded to Dr. Rebecca Cole, an African-American woman who received her medical degree from the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania in 1867. The first “historically black” medical school in the U.S., the Howard University College of Medicine, would not open until 1868. As late as 1920, there were only 65 African-American women doctors in the United States.

Around the time of her graduation, Rebecca married for the second time. (Her first marriage to Wyatt Lee, from 1852 to 1863, ended with his death in 1863.) In 1864, she married Arthur Crumpler. Rebecca began a medical practice in Boston.

After the end of the Civil War in 1865, the Crumplers moved to Richmond, Virginia, where, to use her own words, she found “the proper field for real missionary work and one that would present ample opportunities to become acquainted with the diseases of women and children.” Rebecca worked under the aegis of General Orlando Brown, the Assistant Commissioner of the Freedman’s Bureau for the State of Virginia. The Freedman’s Bureau was the federal agency charged with helping more than 4,000,000 slaves make the stunning transition from bondage to freedom. In Richmond, Rebecca valiantly ignored daily episodes of racism, rude behavior, and sexism from her colleagues, pharmacists, and many others, in order to treat, as she later wrote, “a very large number of the indigent, and others of different classes, in a population of over 30,000 coloreds.”

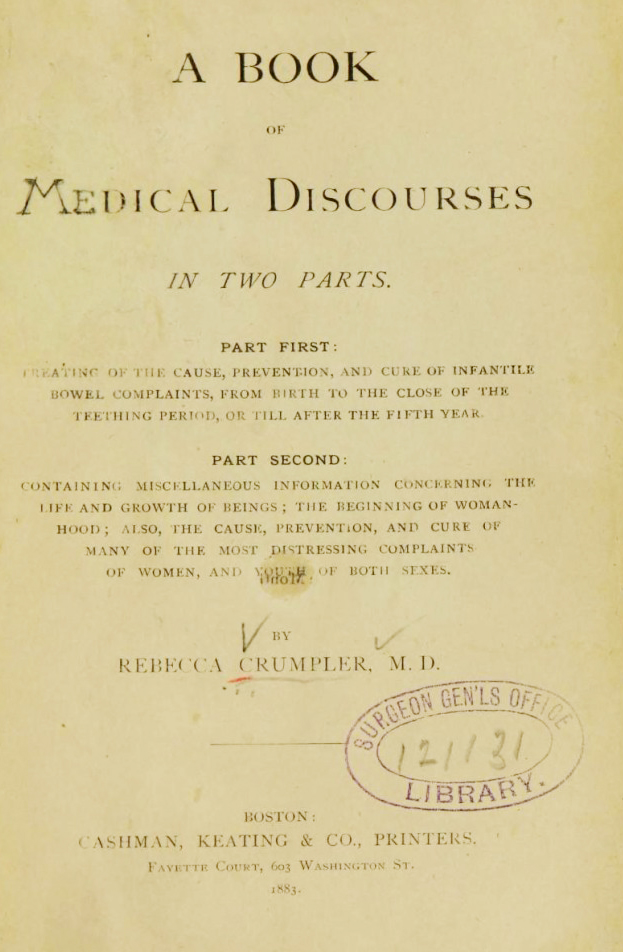

In 1869, the Crumplers returned to Boston and they settled in a predominantly African-American neighborhood on Beacon Hill. She practiced medicine there, as well. In 1880, she and her husband moved, once again, this time to Hyde Park, New York. Although there exists little evidence that she practiced much medicine after this point, she did write a fine book, “A Book of Medical Discourses in Two Parts,” which was published by Cashman, Keating, and Co., of Boston, in 1883.

The book is divided, as the title implies, into two sections. The first part focuses on “treating the cause, prevention, and cure of infantile bowel complaints, from birth to the close of the teething period, or after the fifth year.” The second section contains “miscellaneous information concerning the life and growth of beings; the beginning of womanhood; also, the cause, prevention, and cure of many of the most distressing complaints of women, and youth of both sexes.” The volume, which may well be the first medical text by an African-American author, is dedicated “to mothers, nurses, and all who may desire to mitigate the afflictions of the human race.”

Rebecca Davis Lee Crumpler died on March 9, 1895, in Hyde Park.