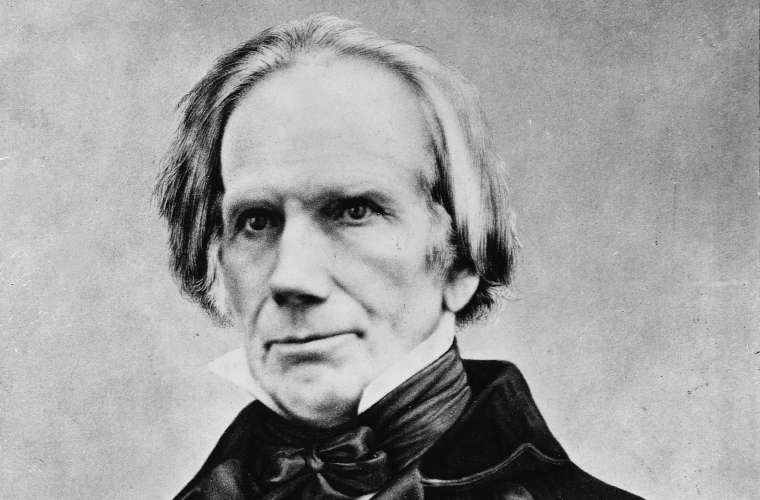

Henry Clay worked as a frontier lawyer before becoming a Kentucky senator and then speaker of the House of Representatives. He was the Secretary of State under John Quincy Adams in the 1820s, later returning to Congress, and pushed for the Compromise of 1850, with overall conflicting stances on race and slavery. A distinguished political leader whose influence extended across both houses of Congress and to the White House, Henry Clay Sr. was born on April 12, 1777, in Hanover County, Virginia.

Clay was raised with modest wealth, the seventh of nine children born to Reverend John and Elizabeth Hudson Clay. His link to American history came at an early age. He was 3 years old when he watched the British troops ransack his family home. In 1797, he was admitted to the Virginia bar. Then, like a number of ambitious young lawyers, Clay moved to Lexington, Kentucky, a hotbed of land-title lawsuits. Clay mingled well in his new home. He was sociable, didn’t hide his tastes for drinking and gambling, and developed a deep love for horses.

Clay’s standing in his adopted state was furthered by his marriage to Lucretia Hart, the daughter of a wealthy Lexington businessman, in 1799. The two remained married for more than 50 years, having 11 children together. His political career kicked off in 1803 when he was elected to the Kentucky General Assembly. Voters gravitated toward Clay’s Jeffersonian politics, which early on saw him push for a liberalization of the state’s constitution. He also strongly opposed the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798.

In the private sector, his work as an attorney brought success and plenty of clients. One of those included Aaron Burr, whom Clay represented in 1806 in a wild case in which Burr was accused of planning an expedition into Spanish Territory and essentially trying to create a new empire. Clay had defended Burr out of a belief that he was innocent, but later, when it was revealed that Burr was guilty of the charges levied against him, Clay spurned his former client’s attempts at making amends.

In 1806, the same year he took on the Burr case, Clay received his first taste of national politics when he was appointed to the U.S. Senate. He was just 29 years old. Over the next few years, Clay served out the unexpired terms in the U.S. Senate. In 1811, Clay was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, where he eventually served as Speaker of the House. In all, Clay would come to serve multiple terms in the U.S. House (1811–14, 1815–21, 1823–25) and Senate (1806–07, 1810–11, 1831–42, 1849–52).

Clay had come to the House as a War Hawk, a leader who vocally pushed his government to confront the British over its conscription of American seamen. In part due to Clay’s political pressure, the United States went to war with Britain in the War of 1812. The conflict proved crucial in forging lasting American independence from England. But while he pushed for war, Clay also showed himself to be crucial in the peacemaking process. When the battles ceased, President James Madison appointed Clay as one of five delegates to negotiate a peace treaty with Britain in Ghent, Belgium.

On other fronts, Clay took some of the biggest issues of the day head-on. He pushed for independence for several Latin American republics, advocated for a national bank and, perhaps most significantly, argued strongly and successfully for a negotiated settlement between enslaved people-owning states and the rest of the country over its western policy. The resulting Missouri Compromise, which passed in 1820, found a necessary balance that allowed for America’s continued western expansion while simultaneously holding off any bloodshed over the white-hot topic of slavery.

Two more times in his political career would Clay step in as lead negotiator and prevent a breakup of the still young United States. In 1833, he walked South Carolina back from the brink of secession. At issue was a series of international tariffs on U.S. exports that had been sparked by American tariffs on imported goods. The cotton and tobacco states of the South were hurt the most by the new tariff agreement, much more so than the industrial north. Clay’s Compromise Tariff of 1833 slowly reduced the tariff rate and eased the tensions between the Andrew Jackson White House and Southern legislators.

In 1850, with the question raised of whether California should become part of the United States as either an enslaved people state or a free state, Clay stepped to the negotiating table once more to stave off bloodshed. In one fell swoop Clay introduced a bill that allowed California to enter the Union as a non-enslaved people state, without an additional enslaved people state as compensation. In addition, the bill covered the settlement of the Texas boundary line, the Fugitive Slave Act, and the abolition of the enslaved people trade in the District of Columbia.

Over the course of his long career, Clay’s skills became renowned in Washington, D.C., earning him the nicknames The Great Compromiser and The Great Pacificator. His influence was so strong that he came to be admired by a young Abraham Lincoln, who referred to Clay as “my beau ideal of a statesman.” Clay quotes often made their way into Lincoln’s speeches. During the writing of his first inaugural address, Lincoln chose a published edition of a Clay speech to keep at his side while he crafted what he’d say to the nation.

“I recognize Clay’s voice, speaking as it ever spoke, for the Union, the Constitution, and the freedom of Mankind,” Lincoln wrote to Clay’s son John in 1864. In 1824, the ambitious Clay set his sights on a new political office: the presidency. But two higher-profile politicians thwarted his candidacy: John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson. When Adams won the presidency, he appointed Clay as his Secretary of State. The appointment came, however, at some personal cost to Clay. With neither Jackson nor Adams able to secure enough electoral votes, the election was thrown to the House of Representatives. Clay parked his support behind Adams with the understanding that he’d have a place in his cabinet. When he received it, Clay’s critics blasted him, with a cry of “bargain and sale.”

The attacks continued into the Adams presidency. Jackson, stung by the defeat, blocked several foreign-policy initiatives put forth by Clay, including securing a trade agreement with Great Britain over the West Indies and sending delegates to a Pan-American Congress in Panama. The backlash against his support for Adams reached its apex when Congressman John Randolph challenged Clay to a duel. Neither man was hurt. In 1828, Jackson captured the presidency from Adams. With Clay’s National Republican Party coming apart at the seams—it would eventually become absorbed by the Whig Party—Clay retired from politics and returned to Kentucky.

But Clay was unable to stay away from Washington. In 1831, he came back to Washington, D.C., and the Senate floor. The following year he headed the National Republicans’ bid to unseat Jackson. At the center of the presidential election was Clay’s support for the renewal of the charter of the Second Bank of the United States, whose creation in 1816 Clay had fought hard for. But the issues around it proved to be Clay’s undoing. Jackson vehemently opposed the bank and the renewal of its charter. He alleged it was a corrupt institution and had helped steer the nation toward higher inflation. The voters sided with him.

After the election Clay remained in the Senate, taking on Jackson and becoming the head of the Whig Party. The decade following his loss to Jackson for the presidency proved to be a frustrating period for Clay. In 1840, he had every reason to expect to be nominated as the Whigs’ candidate for the White House. He did little to hide his frustration when the party turned to General William Henry Harrison, who selected John Tyler as his running mate.

After Harrison’s death just a month into his presidency, Clay tried to dominate Tyler and his administration, but his actions proved futile. In 1842, he retired from the Senate and again returned to Kentucky. Two years later, however, he was back in Washington, when the Whig Party chose him, not Tyler, as its candidate for the 1844 presidential election. But like his run a decade earlier, the election centered around one issue, and this time it was the annexation of Texas.

Clay opposed the move, fearing it would provoke a war with Mexico and reignite the battle between pro-slavery and anti-slavery states. His opponent, James K. Polk, on the other hand, was an ardent supporter of making Texas a state, and the voters, smitten with the idea of Manifest Destiny, sided with him and delivered the White House to Polk. Almost right up until his last days, Clay still played a part in the nation’s politics. Battling tuberculosis, he died on June 29, 1852. Widely respected for his contributions to the country, Clay was laid in state in the Capitol rotunda, the first person ever to receive that honor. In the days that followed his death, funeral ceremonies were held in New York, Washington, and other cities. He was buried in Lexington, Kentucky.