Decades before the Nazis turned to the Jews, German colonialists in Southwest Africa – now Namibia – dehumanized, built death camps for, and slaughtered tens of thousands of tribespeople in systematic genocide. Here, Edwin Black reveals the full horrors of an eerie and odious precursor of the Shoah and its legacy in the US

In recent years, some in the African American community have expressed a disconnect from Holocaust topics, seeing the genocide of Jews as someone else’s nightmare. After all, African Americans are still struggling to achieve general recognition of the barbarity of the Middle Passage, the inhumanity of slavery, the oppression of Jim Crow, and the battle for modern civil rights. For many in that community, the murder of six million Jews and millions of other Europeans happened to other minorities in a faraway place where they had no involvement.

However, a deeper look shows that proto-Nazi ideology before the Third Reich, the wide net of Nazi-era policy, and Hitler’s post-war legacy deeply impacted Africans, Afro-Germans, and African Americans throughout the twentieth century. America’s black community has a mighty stake in this topic. Understanding the German Reich and the Holocaust is important for blacks just as it is for other communities, including Roma, eastern Europeans, people with disabilities, the gay community, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and many other groups in addition to Jews.

The dots are well known to many scholars — but are rarely connected to form a distinct historical nexus for either the Holocaust or the African American communities. This is understandable. The saga behind these connections started decades before the Third Reich came into existence, in a savage episode on another continent that targeted a completely different racial and ethnic group for death and destruction. But the horrors visited on another defenseless group endured and became a template for the Final Solution. Students of the Holocaust are accustomed to looking backward long before the Third Reich and long after the demise of the Nazi war machine. African Americans should do the same.

Germany comes to Africa

It is settled, an everyday history that Nazi Germany aggressed against its neighbors in part because of a twisted concept known as Lebensraum — that is, the self-declared mandate to achieve “living space” for an overcrowded Germany. Lebensraum declared that the Third Reich was inherently entitled to supplant and destroy other nations to advance German biological supremacy. This racist philosophy underpinned Germany’s invasion, subjugation, and rape of much of Eastern Europe. However, students of Lebensraum know it was not a Hitlerian concept. Rather, it was coined in the last gasp of the nineteenth century by German geographer Friedrich Ratzel.

In the second half of the 1800s, Germany suffered massive urban overcrowding due to its shift from an agrarian society to an industrialized nation. As it changed, Germany found itself in the throes of a concomitant population boom and rampant poverty. Low-priced American grain only exacerbated Germany’s economic woes. Germans in large numbers were sleeping on city streets. The social upheaval ignited the so-called “Flight from the East.” In the 1850s, as Beethoven’s Ninth played on for the secure classes, a million desperate Germans boarded steamers with their luggage and their memories, immigrating to American shores. Some 215,000 came in 1854 alone.

Things did not improve in Germany. In the 1880s, another 1.5 million Germans came to America, bringing their beer and brats. Upon arrival to this country, they poured west into such centers as Milwaukee and St. Louis. It was an epic population influx for America that in large measure helped build the continental United States and the nation’s social fabric.

But in the Second Reich, rapid multimillion-person population loss and the tearfully destitute conditions propelling the outflow were devastating to the German national identity. A concept arose: Volk ohne Raum, that is, “a people without space.” As the father of German geopolitics, Ratzel, with his post-Darwinian notions of racial supremacy, insisted that colonizing land to create extra “living space” was the cure for Germany’s urban overcrowding. In those turn-of-the-twentieth-century days, a weakened Germany turned its focus from the Balkans and the Slavic realms to Africa. Indeed, Ratzel wrote that Africa was an ideal candidate for the push to achieve Lebensraum.

Africa, with its wide-open spaces and rugged, romantic beauty, had long beckoned white Europe. By the early 1880s, imperialists in England, Belgium, Portugal, France, and other countries were planning or had inaugurated colonies throughout the African continent. Many were incomprehensibly brutal and exploitative regimes. Kaiser Wilhelm feared Germany would be shut out of Africa and its natural resources, including gold.

The Second Reich enthusiastically joined the so-called “Scramble for Africa.” Beginning in November 1884, Germany convened the Berlin Conference of leading European powers to cooperatively carve up the African continent. Out of that international conclave came an agreement, enacted “in the Name of God Almighty,” that would systemize an orderly territorial invasion by European powers, as well as river navigation, land use, and the other needed “rules for the future occupation of the coast of the African Continent.” As part of the treaty, European governments also agreed to interdict and suppress the Arab slave trade — a lofty moralistic ideal with a double edge. Stemming Arab slave exports also kept able-bodied Africans on the land and available to labor in abject and cruel, slave-like conditions on colonial plantations.

Beginning in 1884, Germany colonized four territories across the breadth of the continent: Togoland, the Cameroons, Tanganyika, and a main coastal presence in Southwest Africa, now known as Namibia. In Southwest Africa, German settlers were able to establish lucrative plantations by exploiting the labor of local Herero and Nama (also known as Hottentot) indigenous peoples. German banks and industrialists combined to provide needed economic support and investment. Berlin dispatched a small military contingent to protect white settlers as they confronted the lightly armed African natives considered subhuman in Germany’s twisted notion of racial hierarchy.

Once entrenched, the German minority established a culture of pure labor enslavement. Tribeswomen were subjected to incessant and often capricious rape — and not infrequently, their men were killed while attempting to defend them. Whites routinely stole the possessions of natives, such as cattle, and found ways to seize ancestral lands over trivialities. Confiscation was often facilitated by predatory European lending practices enforced at gunpoint by the German military. In 1903, on the verge of utter dispossession, Nama warriors revolted against the 2,500-strong white community. Later, Herero fighters joined. Scores of German settlers were massacred in a sequence of surprise attacks. The 700-plus Schutztruppe or “protection force” was overwhelmed. The colonial governor called for reinforcements.

In 1904, Berlin dispatched 14,000 soldiers to suppress the uprising. Lieutenant General Lothar von Trotha, Supreme Commander of German Southwest Africa, had learned from other European battles in Africa, such as Britain’s costly Boer War. Trotha was determined to quickly and completely exterminate the African natives, leaving the land free for the fulfillment of the dream of Lebensraum. Armed with modern cannon and Gatling guns, Trotha’s troops surrounded the Africans on three sides. When Trotha wrote on October 2, 1904, “It is my intention to destroy the rebellious tribes with streams of blood and money,” his men used the German word vernichtung. Vernichtung means extermination.

After decimating the outclassed fighters, Trotha decided to annihilate the civilians as well. His proclamation to the Hereros and the colonists was an open pledge of extermination, unmistakable to all:

“I, the great general of the German soldiers, send this letter to the Hereros. The Hereros are German subjects no longer. … The Herero nation must now leave the country. If it refuses, I shall compel it to do so with the ‘long tube’ (cannon). Any Herero found inside the German frontier, with or without a gun or cattle, will be executed. I shall spare neither women nor children. I shall give the order to drive them away and fire on them. Such are my words to the Herero people.”

Understandably, Trotha’s command became known in official circles as a vernichtungsbefehl, that is, an “extermination order.”

The people mounds of vanquished Hereros, still barely alive and breathing, were set on fire — to finish the business. For many years, their mass murdered bodies littered the desert in nightmarish aggregations of killed humanity

Nearly surrounded, more than 3,000 Hereros were cut down by fusillades. But bullets and cannons were only the beginning. German guide Jan Cloete testified, “I was present when the Herero were defeated in a battle in the vicinity of Waterberg. After the battle, all men, women, and children who fell into German hands, wounded or otherwise, were mercilessly put to death. Then the Germans set off in pursuit of the rest, and all those found by the wayside … were shot down and bayoneted to death. The mass of the Herero men was unarmed and thus unable to offer resistance. They were just trying to get away with their cattle.”

To avoid staining the honor of German soldiers, von Trotha instructed his troops to fire over the heads of women, children, and weakened men, driving them east into the scorching dry Omaheke section of the Kalahari Desert. In anticipation of their flight, troops poisoned the wells or surrounded them with deadly forces. Starved of food or water, the desperate and weakened Herero wandered from watering hole to watering hole.

Thousands, in family groups, gradually fell dead, their rib cages bulging to the limits of their gaunt and emaciated skins. Many who did not die quickly enough were seized — still whimpering — and then stacked by soldiers into human heaps atop makeshift pyres comprised of bush branches and limbs. The people mounds of vanquished Hereros, still barely alive and breathing, were set on fire — to finish the business. For many years, their mass murdered bodies littered the desert in nightmarish aggregations of killed humanity. Whistled by the desert winds and photographed through the lens of eternity, flesh and bones became fleshless bones, as the unburied corpses not completely immolated were finally devoured by desert elements.

A deadly fate also awaited the Nama tribespeople. Trotha sent them a similar message: “The Nama who chooses not to surrender and lets himself be seen in German territory will be shot until all are exterminated.” With the vast majority of the Africans murdered, Berlin rethought the extermination program. What good was maintaining a colony without a local workforce to exploit? Therefore, at some point, those civilian Herero and Nama people and related clans that managed to escape the bullets, cannon shots, killing thirst, and fiery execution were rounded up and sent to concentration camps. Many died on the long march. Others were simply transported to serve in cruel bondage for great German industrial concerns, building roads, berms, and useful holes for the German infrastructure.

One of these camps was the notorious Shark Island Concentration Camp. Shark Island was considered an “extermination by labor” camp where Nama and Herero civilians, including women and children, were knowingly and methodically worked to death. Investigators estimate the death rate at 90 percent, as thousands of defenseless Africans perished under the brutal living conditions, the heavy loads, the piercing elements, and the endless whippings with stinging sjamboks made of rhinoceros or hippopotamus hide awaiting all those who showed either weakness, reluctance, or just slowness of step.

A missionary recalled in shock, “A woman who was so weak from illness that she could not stand, crawled to some of the other prisoners to beg for water. The overseer fired five shots at her. Two shots hit her: one in the thigh, the other smashing her forearm.” One surviving family member of a chief later testified to a British commission, “I was sent to Shark Island by the Germans. We remained on the island for one year. Approximately 3,500 Hottentots Nama, and Kaffirs were sent to the island and only 193 returned — 3,307 died on the Island.”

Scholars commonly say the Armenian genocide of 1914–1915, perpetrated by the Turks, was the first genocide of the twentieth century. That is wrong. History records the first deliberate effort to systematically exterminate an entire group was by the Germans in Southwest Africa, 1904–1908

Another member of the German settlement wrote, “During the worst period an average of thirty died daily … it was the way the system worked. General von Trotha publicly gave expression to this system of murder through work in an article he published. … ‘The destruction of all rebellious tribes is the aim of our efforts.’”

At the beginning of the German occupation, Herero society was estimated at 80,000 to 90,000 souls. Some 50,000 Africans comprising other tribal groups, created a total approximate native population of about 130,000 to 140,000. By the time the cannon smoke cleared and the injured stopped breathing, only about 15,000 broken Hereros remained to be dragged for labor. In 1911, after hostilities had ceased and the extermination policy was challenged in Berlin, an official German census counted an 80 percent reduction of all tribal groups, or about 92,000 dead in the preceding few years.

Settlements Commissioner Paul Rohrbach insisted, “To secure the peaceful white settlement against the bad, culturally inept, and predatory native tribe, its actual eradication may become necessary.” Even still, Rohrbach bemoaned that so many sheep and cows had to die along with the Hereros, due to the sweeping nature of Trotha’s Vernichtungs Prinzep, or extermination policy. He chastised that it was a waste to lose that much livestock.

Scholars commonly say the Armenian genocide of 1914-1915, perpetrated by the Turks, was the first genocide of the twentieth century. That is wrong. History records that the first deliberate effort to systematically exterminate an entire group was by the Germans in Southwest Africa, 1904-1908.

Yet the systematic slaughter of the Hereros and related African groups was hardly a secret genocide. The sanctioned extermination was long debated in the Reichstag —was too much or too little force applied? In one 1906 Reichstag session, Chancellor Bernhard von Bülow read a newspaper letter explaining, “Around 2,000 Hereros are presently under German imprisonment. They surrendered against the guarantee of life, but were nevertheless transferred to Shark Island in Lüderitz, where, as a doctor assured me, they will all die within two years due to the climate.”

Coveted medals were awarded to the military leaders. A heroic national myth was invented to glamorize the German conquest and victory, complete with grandiose horse-mounted soldier statuary in public squares both in Germany and Africa. Germany’s military establishment compiled a two-volume official report for study at its academies. The entire campaign was justified and elevated along numerous social and military planes. Published memoirs, artworks, and geopolitical promulgations enshrined the supposed gallantry of the extermination of the Hereros.

Africa comes to Germany

After World War I, Germany was stripped of its African colonies as part of the Treaty of Versailles. German Southwest Africa and its other African colonies were set on a path to independence, albeit under close direct and indirect European tutelage. The loss of its colonies might have convinced many Germans that Africa was part of a dark past. Not so. Conscription and recruitment had been introduced into France’s African territories decades earlier. Nearly half a million fearsome fighters, mainly from Senegal, Algeria, Tunisia, and Morocco — all generally referred to as Senegalese Tirailleurs regardless of their national origins — fought in the French Army in World War I. At times, Africans comprised about 14 percent of the wartime French army. During World War I, French Colonial African regiments fought in great numbers in the European theater.

The Treaty of Versailles, in Article 428, stipulated that the Allies would occupy the Rhineland for fifteen years. In 1919, French troops occupied this part of Western Germany. Between 20,000 and 40,000 of these occupying soldiers were Senegalese Tirailleurs — about half from Arab North Africa, and about half from central and interior Africa. The presence of African soldiers in authority caused hysteria in Germany and shock on both sides of the Atlantic. Germans popularized a national panic over the so-called “Black Horror on the Rhine.” Deviant racial sexual imagery, including caricatures of monkey-like soldiers — often possessed of giant phalluses — ravaging helpless German damsels spread widely in print and public discourse.

Everywhere, fear gripped German society that its racial superiority would be poisoned by Negro blood

By 1920, mass rallies had been convened in 25 German cities, including one with 50,000 attendees at Hamburg’s Sagebiel Hall. Sympathetic rallies by German-American groups were organized across the United States by “The American Campaign against the Horror on the Rhine.” One such demonstration at Madison Square Garden attracted 12,000 protesters of Irish and German descent. In the contentious presidential contest of 1920, some supporters of Warren G. Harding were fond of verbalizing support for his apparent promise that “he would do his best to get those niggers out of Germany.” Even Pope Benedict XV and his successor Pius XI voiced objection to African presence on German soil.

Occupation by African soldiers was seen among the German people as a further wound-salting French humiliation of German honor and prestige. Certainly, there were a number of rapes, but there were also consensual marriages as people mixed. From these came a class of mixed-race Afro-Germans popularly called mulattos. Estimates vary widely, but many observers surmise some 20,000 mulattos, that is, Afro-Germans with legal German citizenship, were now amongst them. Everywhere, fear gripped German society that its racial superiority would be poisoned by Negro blood. The “Black Horror on the Rhine” coincided with the advent of American and international eugenics, a pseudoscience born on Long Island that found intellectual partnership with German racists of the day.

Eugenics was an early twentieth-century American crusade to create a white, blond, blue-eyed, Germanic utopian society that would rise following the systematic elimination of all people of color or of unwanted mixed ancestry. A famous founding document of the American movement was a 1912 German study, The Bastards of Rehoboth and the Problem of Miscegenation in Man, which claimed to document the corrupted moral and biological nature of black-white offspring. The author was a German biologist and race scientist Eugen Fischer.

He was stationed in colonial Southwest Africa, where he studied local Dutch-African families cited in the work. From studies such as Fischer’s sprang the fraudulent science of American eugenics that medicalized racial theory. Propelled by abundant financing from the Carnegie Institution, Harriman Railroad fortune, and Rockefeller Foundation, eugenics ultimately led to the sterilization of some 60,000 Americans under laws in 27 states, as well as racial and ethnic incarceration.

Carnegie and Rockefeller poured millions of dollars into proliferating the pseudoscience in Germany after World War I. Average Germans everywhere embraced the American theories, elevating their visceral racial hatred into an entrenched university science with broad acceptance. The German and global public outcry against claimed biological and cultural debasement by French African troops finally got its way in May 1920, when Paris announced its troops were almost entirely being transferred to the Mideast to fight the war against Arab nationalism in Syria.

But if in late 1920, Germany once again thought its juncture with Africa was over, they were wrong. Thousands of French African soldiers returned in 1923. The Treaty of Versailles had imposed a massive $33 billion war debt on the newly established Weimar Republic, the successor to the Second Reich. Germany struggled to pay its debt in cash and raw materials. When it defaulted on the delivery of 140,000 telegraph poles, thousands of French troops occupied Germany’s Ruhr industrial region to seize the value of local factory output. German workers walked out on a general strike. Berlin began printing worthless money to support the striking families — which led to the famous hyperinflation, where worthless cash was carted in wheelbarrows to buy bread.

From colonialist to Nazi

With Germany roiled by socioeconomic and political chaos and the fright of French African troops in many streets, the militarized rabble of Germany’s recent wars rose again. They were determined to turn back the clock and achieve a racial and territorial triumph. The pervasive ghastly legacy of Southwest Africa and the concomitant panic over the “Black Horror on the Rhine,” combined with unrelated factors such as the rise of communism, German imperial humiliation, a global economic Depression, and seething anti-Semitism produced a combustible fascist mix. Out of this mix came the Nazis, led by Adolf Hitler. Nazi crimes, Hitler’s henchmen, and their methodologies are well known. Their nexus with Southwest Africa is less known.

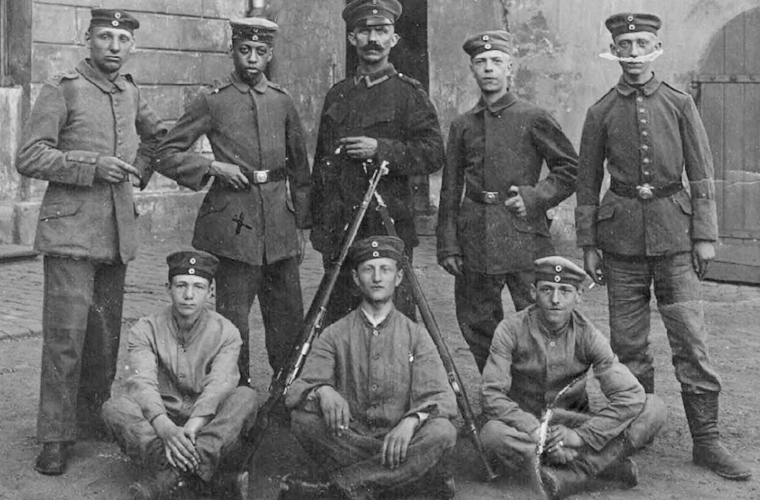

The Sturmabteilung — the Storm Troopers — wore brown shirts. Why brown? Many early Nazis served in the Schutztruppe, the military units that had operated in Southwest Africa. Recalling German colonial grandeur, Nazi Storm Troopers purchased surplus Schutztruppe uniforms, light brown for service on the Kalahari Desert in the Southwest Africa realm. Hermann Goering rose as one of the Nazi triumvirate, second only to Hitler. The first Reichskommissar, or Governor, of German Southwest Africa, was Goering’s father, Heinrich. The elder Goering was among the first to confront the Herero. For decades, a main street in the Southwest African settlement immortalized his name — Heinrich Goering Street.

For his part, Hermann was captivated by his father’s exploits in Africa. Goering’s 1939 official Nazi biography records reveal that the young Goering “was even more thrilled by his father’s accounts of his pioneer work as Reichskommissar for South-West Africa … and his fights with the Herero.” Years later, Goering swore under oath that of the leading “points which are significant with relation to my later development,” he counted among the top four as “the position of my father as first Governor of Southwest Africa.”