Oney Judge was the enslaved personal attendant of Martha Custis Washington when she ran away from the President’s House in Philadelphia in 1796. Born about 1773 at Mount Vernon, Judge began laboring in the mansion when she was ten years old. After George Washington was elected president in 1789, she accompanied the family to New York and then, when the federal capital moved, to Philadelphia. On May 21, 1796, she escaped from the president’s mansion while the family ate dinner and boarded a ship for Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Washington’s agents tracked her there, twice speaking with her, in 1796 and 1799, but failing to apprehend her. Judge married the free black sailor John Staines in 1797 and the couple had three children before his death in 1803. Oney Judge Staines lived the rest of her life in poverty. In 1845 and 1847 she gave interviews to abolitionist newspapers, recounting the story of her life with the Washington family and her escape from slavery. She died in Greenland, New Hampshire, in 1848.

Oney Judge was born about 1773 at Mount Vernon, the Fairfax County plantation of George Washington. She is listed as twelve years old in an inventory of slaves prepared by Washington and dated February 18, 1786. A newspaper report from 1845 noted that her name at the time of her escape had been Ona Maria Judge. Oney is a nickname that appears in Washington’s papers and in advertisements for her return. In a 1796 letter Washington referred to “Oney Judge as she called herself while with us.” Judge was the daughter of Betty, an enslaved seamstress, and probably the English tailor Andrew Judge, an indentured servant who labored at Mount Vernon from 1772 until about 1780. Through her mother, Judge had four half-siblings: Austin, whose father is unknown; Tom Davis and Betty Davis, the children of an indentured weaver named Thomas Davis; and Philadelphia (later Philadelphia Costin).

Judge recalled receiving no education or religious instruction as a child. At the age of ten, she became the body servant of Martha Washington. On February 4, 1789, George Washington was elected president, and in April he left for New York, the federal capital. On May 16, Martha Washington and her household, including Judge, Austin, and five other slaves, left Mount Vernon to join him. They lived in New York for just more than a year, returning to Mount Vernon for an extended visit on August 30, 1790. In the meantime, the capital had moved to Philadelphia, where the Washingtons traveled in November, again with Judge and her half-brother.

In the spring of 1791, George Washington learned that Pennsylvania law complicated his ability to hold slaves in the state. Passed in 1780, “An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery” required that any slaves living in Pennsylvania for six uninterrupted months be freed. In a letter to his personal secretary, dated April 12, 1791, Washington ordered that his slaves be sent back to Virginia before their six months expired in May, and then returned to Philadelphia. It is unclear whether he was aware of a 1788 amendment to the Pennsylvania act that prohibited exactly this means of subverting the law. There also was some confusion at the time over whether federal officials were exempt from the law’s requirements and, if they were not, whether Pennsylvania would enforce them in such a politically sensitive situation.

Whatever the case, Washington took no chances, explaining to his secretary that the movement of his slaves ought to be accomplished “under the pretext that may deceive both them and the Public.” Washington worried that should his slaves learn of the law they might be tempted by freedom. He also noted that all but two of his slaves in Philadelphia, including Judge and Austin, were dower slaves, meaning that they had come to the marriage with his wife and were technically owned by the estate of her first husband, Daniel Parke Custis. Should he lose them, Washington wrote, he would be forced to reimburse the Custis estate.

For the next five years, Judge remained in Philadelphia, with discreet trips out of state occurring every six months. On March 21, 1796, Martha Washington’s granddaughter, Elizabeth Parke Custis, married Thomas Law, an Englishman twenty years her senior. Judge learned that she was to be given to the couple as a gift, perhaps after the Washingtons’ death. She later told a reporter that she was “determined” never to be the slave of Elizabeth Custis Law.

Escape

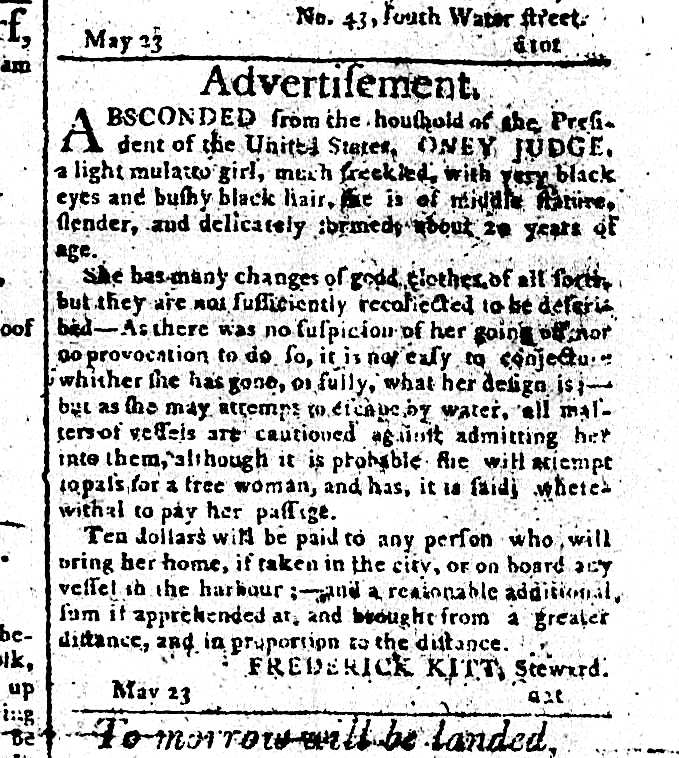

Judge fled the President’s House in Philadelphia on May 21, 1796, while the family ate dinner. Soon after, she boarded the Nancy, a sloop captained by John Bowles and bound for Portsmouth, New Hampshire. There she likely found aid with the city’s free black population. Notices offering a $10 reward for her return appeared on May 24 in the Philadelphia Gazette and Universal Daily Advertiser and, a day later, in Claypoole’s American Daily Advertiser. Washington alerted various friends and associates to Judge’s escape, and on June 28, Thomas Lee, the son of Richard Henry Lee, wrote to inform the president that his slave had been sighted in New York. Later in the summer, another report placed her in Portsmouth. Elizabeth Langdon, the daughter of U.S. senator John Langdon and a past visitor to Mount Vernon, recognized Judge on the street.

On September 1, 1796, Washington wrote to his secretary of the Treasury, Oliver Wolcott Jr., demanding that he engage the customs collector at Portsmouth to apprehend the missing slave. Judge, he wrote, should be seized and—in an apparent violation of the Fugitive Slave Act, which required that fugitive slaves appear before a local magistrate—be immediately sent to Alexandria. Washington apologized to Wolcott for the request, “but the ingratitude of the girl,” he wrote, “who was brought up & treated more like a child than a servant (& Mrs. Washington’s desire to recover her) ought not to escape with impunity if it can be avoided.”

Joseph Whipple, the customs collector, succeeded in interviewing Judge on the ruse that he was interested in hiring her as a maid. He even arranged for her to travel to Virginia, but she failed to appear at the designated time. In a letter to Wolcott, dated October 4, 1796, Whipple wrote that Judge was willing to return only if she were promised her freedom upon Washington’s death. Otherwise, she possessed “a thirst for complete freedom” and “should rather suffer death than return to Slavery.” Washington wrote directly to Whipple on November 28 that if Judge returned voluntarily, with no promise of freedom, “her late conduct will be forgiven by her Mistress.” If not, then she should be removed forcibly. In a reply dated December 22, Whipple apologized for his failure to apprehend Judge, promised to do his best, and, remarkably, advocated for the gradual abolition of slavery.

Washington made one final attempt to capture his slave before his death in December 1799. On August 11 of that year, he wrote his wife’s nephew, Burwell Bassett Jr., who was then serving in the Senate of Virginia, requesting that he travel to New Hampshire. While taking care to avoid anything “unpleasant, or troublesome,” Washington wrote, he should find Judge and bring her back to Virginia. In Portsmouth Bassett stayed with Senator Langdon, who told him where Judge lived. Like Joseph Whipple before him, Bassett was unable to convince her to leave. Also like Whipple, he did not immediately take her into custody, and when at some unknown time he returned to her home she was gone.

Later Years

On January 8, 1797, Judge and the free black sailor John Staines, known as Jack, received a certificate of marriage in Greenland, New Hampshire. The ceremony was performed by Samuel Haven, minister of the South Church Congregational church of Portsmouth. The couple had two daughters and a son.

After Jack Staines’s death in 1803, the family became impoverished, moving in with the Jacks, a free black family in Greenland. In August 1816 Oney Staines sent her daughters to labor as indentured servants with a neighbor. Her son became a sailor. All three children were dead by 1845, when Thomas H. Archibald, a Baptist minister, visited Staines. In his interview, which appeared on May 22 in the Granite Freeman, an abolitionist newspaper published in Concord, New Hampshire, Staines described her life with the Washingtons and her escape from Philadelphia: “When asked if she was not sorry she left Washington, as she had labored so much harder since than before, her reply is, ‘No, I am free, and have, I trust, been made a child of God by the means.’” A second interview, conducted by Benjamin Chase, appeared in the abolitionist paper the Liberator on January 1, 1847.

Staines died in Greenland on February 25, 1848.