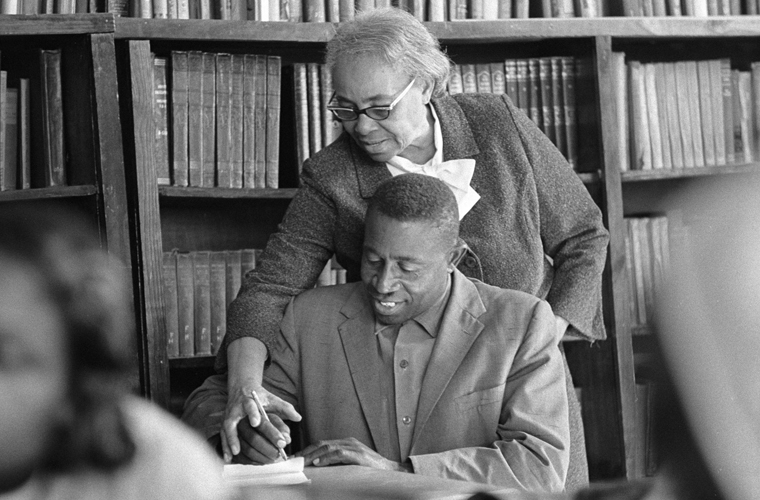

Septima Poinsette Clark was a prominent figure in the Civil Rights Movement and made significant contributions to the fight for racial equality in the United States. Born on May 3, 1898, in Charleston, South Carolina, she dedicated her life to advocating for social justice and empowering African Americans through education and activism. Clark’s early experiences with racism and discrimination fueled her passion for civil rights. Despite facing numerous obstacles, including being denied the opportunity to attend college due to her race, she remained determined to make a difference. In 1916, she began her career as a teacher in rural South Carolina, where she witnessed the inequalities and injustices faced by African American students. This experience solidified her commitment to challenging the status quo and fighting for equal rights.

In the 1940s, Clark became involved with the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) and worked tirelessly to register African American voters in the South. She also played a pivotal role in organizing citizenship schools, which provided adult education and voter registration training to empower African Americans to participate in the democratic process. These efforts were instrumental in increasing voter turnout among African Americans and challenging discriminatory voting practices.

One of Clark’s most significant contributions was her role in the development of the Citizenship Education Program (CEP), which was established by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in 1961. As the program’s director, she trained thousands of grassroots activists in nonviolent resistance, community organizing, and leadership skills. The CEP played a crucial role in mobilizing African American communities and empowering individuals to advocate for their rights in a peaceful and strategic manner.

In addition to her activism, Clark was a fervent advocate for education and believed that knowledge was essential for empowerment. She emphasized the importance of literacy and education as tools for liberation and encouraged African Americans to pursue learning opportunities despite the systemic barriers they faced. Her commitment to education led her to become the first African American woman on the staff of the Highlander Folk School, where she developed innovative teaching methods and curriculum to empower marginalized communities.

Clark’s influence extended beyond the United States, as she traveled internationally to share her expertise in grassroots organizing and nonviolent resistance. She collaborated with civil rights leaders around the world and inspired countless individuals to join the struggle for justice and equality.

Throughout her lifetime, Septima Poinsette Clark demonstrated unwavering courage, resilience, and determination in the face of adversity. Her legacy continues to inspire future generations of activists and advocates for social change. By challenging injustice, promoting education, and empowering marginalized communities, she left an indelible mark on the Civil Rights Movement and the ongoing fight for equality.

Septima Poinsette Clark’s impact on civil rights and social justice serves as a reminder of the power of grassroots activism and the importance of education in creating lasting change. Her legacy continues to resonate today, as her contributions have paved the way for progress in the pursuit of equality and justice for all.