The scramble for Africa, a British term coined in 1884, describes the more than twenty-year period when European powers explored, partitioned, and conquered nearly 90 percent of the African continent. An observer at the time described it as “one of the most remarkable episodes in the history of the world.”

Scholars disagree on the exact origins of the scramble. Most date its beginning to the 1870s and its conclusion to 1902, with the British defeat of the Boers (now Afrikaners) in South Africa. Explanations for what provoked such rapid conquest fall into two broad categories. The “Eurocentric” explanation contends that European competition for new markets and investments drove the imperialist expansion, while the “Afrocentric theory” focuses on the conflicts between African states and peoples. Others contend that it was a combination of the two.

The historical progression of the scramble is clearer. In the mid-1800s European presence on the continent was limited to coastal regions and a few interior areas in the south and east. In 1876, however, Belgium’s King Leopold II announced his intent to explore the Congo region, and in 1879 Leopold sent Sir Henry Morton Stanley to the area. In the same year, the French began building a railway east of Dakar, hoping to tap potentially huge Sahelian markets. That year France also joined Great Britain in taking financial control of Egypt.

Tensions between the European powers seeking African spheres of influence increased. In response, Chancellor Otto von Bismarck of Germany convened the Berlin Conference of 1884–1885. The European participants at the conference recognized King Leopold as the legitimate authority in the Congo basin, but, more importantly, it was decided that a European power could only claim an area of Africa that it “effectively occupied.” The first phase of the scramble was largely a paper conquest, conducted in the drawing rooms of European capitals. On the continent, explorers and soldiers such as Stanley, Pierre de Brazza, Frederick Lugard, and Cecil Rhodes acted as agents of European power, conquering weak African chiefs and signing treaties with powerful ones.

In the early 1890s, treaty-making gave way to conquest. Advances in military technology and medicine (especially the discovery of the antimalarial agent quinine) enabled Europeans to send troops into the heart of the continent, where the persistence of inter-African wars facilitated European conquest. Although European firepower crushed most African resistance movements, others, such as those waged by the Boers, Ndebele, and Zulu in southern Africa, the Baule in Côte d’Ivoire, and the Mahdi in Sudan, fought off colonial armies for several years. In Ethiopia, Emperor Menelik II defeated Italian colonization efforts altogether.

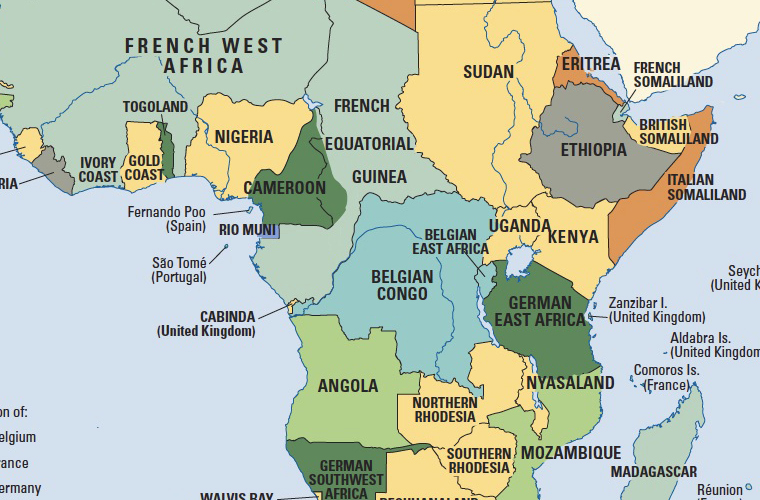

In half a generation France, Germany, Great Britain, Italy, Portugal, Spain, and King Leopold II of Belgium had acquired thirty new African colonies or protectorates, covering 16 million sq km (6 million sq mi). They had divided a population of approximately 110 million Africans into forty new political units, with some 30 percent of the borders drawn as straight lines, cutting through villages, ethnic groups, and African kingdoms.