A Historical Overview

The transatlantic slave trade, one of the darkest chapters in human history, involved the transportation of millions of Africans to the Americas as part of the triangular trade route. Central to this trade were the slave ships, which played a pivotal role in the dehumanizing and brutal journey of enslaved individuals from Africa to the New World. These vessels, ranging in size and design, were instrumental in perpetuating the horrors of the Middle Passage. Slave ships varied widely in size, from small ten-ton vessels to larger ships like the 566-ton Parr. The design and capacity of these ships were adapted to accommodate the transportation of enslaved individuals, with modifications such as portholes for better airflow and copper-sheathed hulls to combat tropical water conditions. The living conditions for the enslaved Africans aboard these ships were deplorable, with limited space, poor ventilation, and unsanitary conditions.

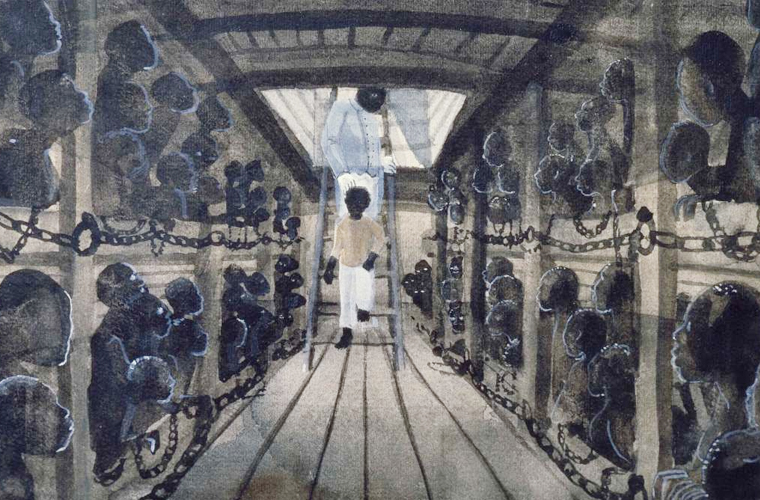

The lower decks of these vessels were divided into separate compartments for men and women, with men often shackled together and women confined below. Children, who were allowed to roam the ship, were used by adults as a means of communication and, in some cases, to plan insurrections. The harsh and inhumane conditions below deck led to rampant disease, with dysentery being the leading cause of death. The mortality rate among both the enslaved individuals and the crew was alarmingly high. The crew of these slave ships faced their own set of challenges and dangers. Often forced into service due to debts or legal issues, crew members endured backbreaking work, violence, and exposure to diseases prevalent along the African coast. The mortality rate among sailors was staggering, with many succumbing to the same diseases that ravaged the captive Africans.

The role of the captain was pivotal in maintaining order and discipline on board. Instances of rebellion or mutiny were met with brutal reprisals, including physical punishment and terrorization. The routine violence employed by the captain and officers permeated through the ranks, creating an environment of fear and despair. One of the most notorious incidents in the annals of the slave trade occurred aboard the slave ship Zong in 1781. The captain, fearing an outbreak of disease and seeking financial gain, ordered the throwing overboard of 122 living Africans. This heinous act, along with other instances of extreme violence, underscores the inhumane treatment endured by those subjected to the horrors of the transatlantic slave trade.

The enduring legacy of the transatlantic slave trade and the role of slave ships in perpetuating this abhorrent system cannot be overstated. The suffering and trauma inflicted on millions of individuals during this dark period in history continue to reverberate through generations. It is imperative to remember and acknowledge this painful chapter in human history as we strive to ensure that such atrocities are never repeated.

The slave ships that plied the waters of the Atlantic Ocean were instrumental in perpetuating the horrors of the transatlantic slave trade. The deplorable conditions aboard these vessels, coupled with the inhumane treatment meted out to the enslaved individuals and crew, stand as a stark reminder of humanity’s capacity for cruelty. As we reflect on this dark chapter in history, it is incumbent upon us to honor the memory of those who suffered and strive to build a world free from oppression and injustice.