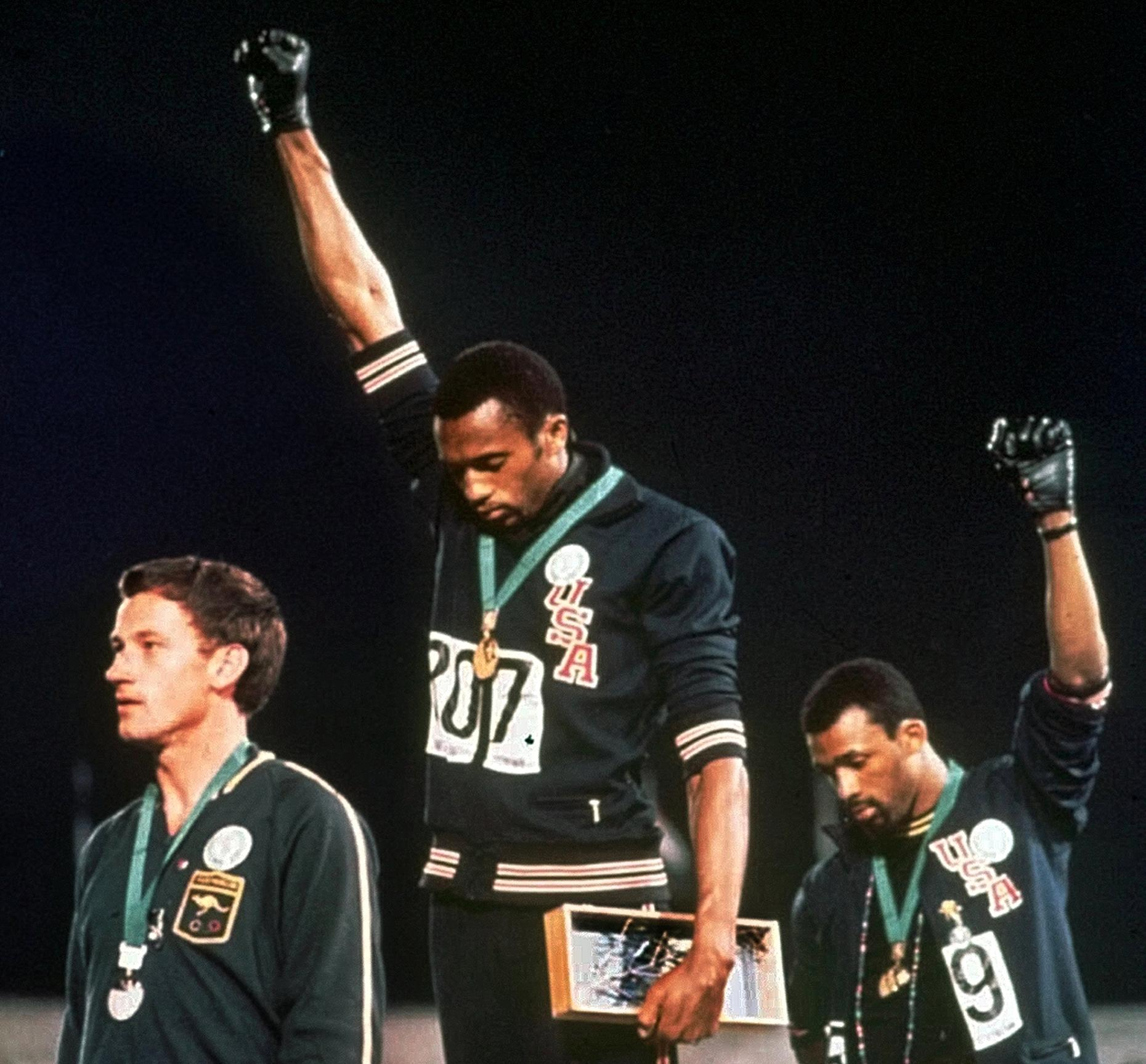

Wearing beads and scarves to oppose lynchings and black socks with no shoes to highlight poverty, African American sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos took to the podium during the October 16, 1968, Olympic medal ceremony in Mexico City to receive their respective gold and bronze medals in the 200-meter race. But it was a single accessory—a black glove—and an accompanying gesture—a raised fist during the American national anthem—that sparked an uproar. From that moment, the two athletes would be vilified, threatened and, in some circles, celebrated.

Using the Olympic medal ceremony to show solidarity with oppressed Black people worldwide impacted both the professional and the personal lives of Smith and Carlos for years afterward. Widely deemed a “Black Power salute,” the men’s gesture at the podium was by no means a random act. Instead, historians say, it was a direct outgrowth of the political climate in the late 1960s.

Both the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. and U.S. Sen. Robert F. Kennedy had been assassinated in 1968. Civil unrest spurred by King’s killing and racial injustice spread throughout multiple cities. Vietnam War protests on and off college campuses also spread nationally. The violence police unleashed on these protesters, notably at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, made international headlines. Although King had consistently preached a message of nonviolence before his death, his assassination, and widespread police brutality led younger activists to determine that a militant political approach would better serve them.

“Within this rise of Black power, we see athletes making very necessary connections in terms of things that they faced within sports and also things that they faced in society writ large, and also understanding that athletes had a platform that they could put to use…,” says Amy Bass, professor of sport studies at Manhattanville College and author of Not the Triumph but the Struggle: The 1968 Olympics and the Making of the Black Athlete. “The spotlight that they had is a rare spotlight for Black men in 1968. So being able to commit a peaceful meaningful global protest, my goodness, that’s a one-in-a-million chance.”

The Olympic Project for Human Rights

Students at San Jose State University, Smith and Carlos were keenly aware of the political issues of the day and the oppression that marginalized groups faced. San Jose State sociology professor Harry Edwards founded the Olympic Project for Human Rights, which included Smith and Carlos as leaders. The project focused on the welfare of Black people globally and advocated for Black athletes. Specifically, they fought for the hiring of Black coaches and the barring of South Africa and (what is now) Zimbabwe from the Olympics for practicing apartheid.

“Edwards sort of painted himself as the originator of Black athletes making protests in American history and around the globe,” says Mark S. Dyreson, a Penn State kinesiology professor, and affiliate history professor. “He’s standing on the shoulders of people like Jackie Robinson, Mal Whitfield, Jesse Owens, and dozens of athletes that people have forgotten about.”

According to Dyreson, Edwards suggested that athletes from older generations, such as Robinson, did not push hard enough for racial equality off the playing field. This overlooked Robinson’s efforts in supporting the U.S. civil rights movement and against South African apartheid. “There’s this much older history of Black athletic activism that’s on the field and off,” Dyreson adds. Smith and Carlos benefitted from the activism of athletes who had predated them. Track and field, for example, had desegregated in the early 20th century on many college campuses and other settings. Those involved in the Olympic Project for Human Rights, including Smith and Carlos, contemplated boycotting the games. While Lou Alcindor (now Kareem Abdul-Jabbar) chose to sit out the event, Smith and Carlos opted to attend, in part, because of the opportunity to address their human rights concerns before tens of thousands of spectators.

“They demand things like the restoration of Muhammad Ali’s boxing title because he was a conscientious objector in Vietnam,” Bass says. “They’re demanding Black coaches being added to the United States Olympic team, they’re demanding that Black members be added to the International Olympic Committee and they’re threatening this boycott, but most of them do go and what they sort of vote on is to protest individually.”

In addition to better treatment for people of African descent worldwide, Smith and Carlos were gravely concerned over an event that happened 10 days before the Summer Games began. On October 2, 1968, Mexican military troops and police officers shot into a crowd of unarmed student protesters, killing as many as 300 youths (official estimates of the number of dead remain uncertain). This incident, along with their existing concerns about human rights, influenced the pair to make a political statement at the Olympics.

After winning the gold and the bronze medals in the 200-meter race (a white Australian athlete named Peter Norman won the silver), the duo stepped up to the podium wearing their symbolic beads, scarves, socks, and gloved fists. Carlos used a black T-shirt to conceal the “USA” on his uniform to “reflect the shame I felt that my country was traveling at a snail’s pace toward something that should be obvious to all people of goodwill,” he explained later in his book, The John Carlos Story: The Sports Moment That Changed the World. Both men also wore Olympic Project for Human Rights badges, as did Norman, who’d asked how he could support their cause.

haring just one pair of gloves—Smith wore a glove on his right hand, and Carlos wore one on his left—the Black Olympians raised their fists as “The Star-Spangled Banner” began. “The stadium became eerily quiet,” Carlos recalled in his memoir. “…There’s something awful about hearing 50,000 people go silent, like being in the eye of a hurricane.” He remembered that some spectators booed them, while others shouted the national anthem at them in defiance. “They screamed it to the point where it seemed less a national anthem than a barbaric call to arms,” he wrote.

Smith and Carlos Face Repercussions

Bass notes how coverage of the gesture was amplified in the United States because the 1968 Olympics marked the first time an American network had broadcast the Games. “It was a big deal,” she says. “Before that, you had sort of 15-minute snippets of updates . . . and suddenly you had 44 hours of coverage. So, there are like 400 million eyes on Smith and Carlos. That’s the power of post-World War II media as it’s emerging.” For their peaceful protest, Smith and Carlos were suspended from the U.S. Olympic team and forced out of the Olympic Village. Death threats awaited them when they made it back to the United States. Their political statement cost them greatly, according to Douglas Hartmann, author of Race, Culture, and the Revolt of the Black Athlete: The 1968 Olympic Protests and Their Aftermath.

“The vast majority of Americans saw them as traitors, as villains or, at least, as unAmerican, unpatriotic,” Hartmann says. For Smith, who was in the ROTC at the time, “That was the end of his military aspirations. Both experienced major personal challenges. Their marriages fell apart. Carlos had difficulty getting employment for many years.” The pair briefly became NFL stars, with Smith playing three seasons for the Cincinnati Bengals, and Carlos playing one year for the Philadelphia Eagles and another for the Canadian Football League. Carlos went on to become a community liaison for the 1984 Los Angeles Summer Olympics.

Both men also worked in educational settings. In 1972, Smith coached track at Oberlin College, an academic institution long known for being racially progressive. After Oberlin, Smith taught sociology and coached cross-country and track at Santa Monica College near Los Angeles. And Carlos took a job as a guidance counselor at Palm Springs High School in Southern California.

In the decades that passed, Smith took care not to describe the gesture he and Carlos made as a Black Power salute. Rather, Smith said the act “stood for the community and power in Black America,” Hartmann says. “He didn’t want to be seen as a radical. He was far more of a kind of traditional American individualist. You know, he was planning to go into the military. He was a patriot. He thought we needed to make a lot of changes on race, but it wasn’t necessarily from a radical political point of view.”

President Obama Honors Smith and Carlos

In 2008, 40 years after they raised their fists during their Olympic medal ceremony, Smith and John Carlos were honored with Arthur Ashe Award for Courage. Eight years later, then-President Barack Obama recognized them during a White House ceremony. “Their powerful silent protest in the 1968 Games was controversial, but it woke folks up and created greater opportunity for those that followed,” Obama said of Smith and Carlos, who were asked to become U.S. Olympic Committee ambassadors in 2016.

Their gesture is considered one of the most political in the history of the modern Olympic Games. But Smith remarked in the HBO documentary Fists of Freedom: The Story of the ’68 Summer Games that the act did not symbolize a hatred for the U.S. flag but an acknowledgment of it.

Historian Edward Widmer, a professor at the Macaulay Honors College at the City University of New York, says it embarrassed the leadership of the United States. “It was a real reminder to the world that the U.S., which preaches human rights and democracy, was not always so strong on human rights in its own country.” But, Widmer adds, “It’s clear it was actually a very patriotic gesture. Smith and Carlos wanted America to be better and to be just for all of its people, so it was calling on America to be a better country.”