By DeNeen L. Brown

In 1844, all black people were ordered to get out of Oregon Country, the expansive territory under American rule that stretched from the Pacific coast to the Rocky Mountains.

Those who refused to leave could be severely whipped, the provisional government law declared, by “not less than twenty or more than thirty-nine stripes” to be repeated every six months until they left.

Oregon Country’s provisional government, which was led by Peter Burnett, a former slaver holder who came west from Missouri by wagon train, passed the law in 1844 — 15 years before Oregon became a state. The law allowed slave holders to keep their slaves for a maximum of three years. After the grace period, all black people — those considered freed or enslaved — were required to leave Oregon Country. Black women were given three years to get out; black men were required to leave in two.

The law became known as the “Peter Burnett Lash Law.” Burnett, who also opposed Chinese migration to Oregon Country, would later become the first American governor of California.

The “Lash Law” was quickly amended and then repealed. No black people were ever lashed under the law.

But the act would become the first of three “exclusion laws” that shaped the Pacific Northwest, banning any additional black people from coming to Oregon Country. Those laws created what one African American professor calls “a very hostile environment” that has long made Oregon and its largest city, Portland, a stronghold for white supremacists like Jeremy Joseph Christian, the man accused of killing two men and severely wounding another on a light-rail train last month.

Few people are aware of Oregon’s history of blatant racism, including its refusal to ratify the 14th and 15th Amendments of the Constitution.

In 1848, the territorial government passed a law making it illegal for any “Negro or Mullatto” to live in Oregon Country. In 1850, under the Oregon Donation Land Act, “whites and half breed Indians” were granted 650 acres of land from the government. But any other person of color was excluded from claiming land in Oregon. In 1851, Jacob Vanderpool, the black owner of a saloon, restaurant, and boarding home, was actually expelled from Oregon territory.

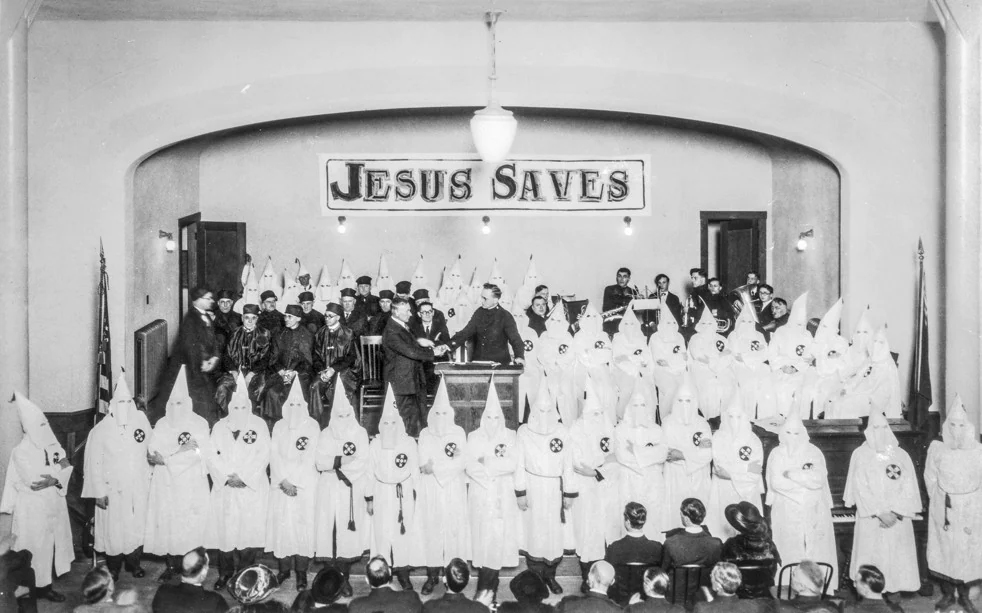

A Ku Klux Klan parade, East Main Street in Ashland, Ore., in the 1920s

A Ku Klux Klan parade, East Main Street in Ashland, Ore., in the 1920s

“The exclusion laws were primarily intended to prevent blacks from settling in Oregon, not to kick out those who were already here,” according to Salem Public Library records. But Vanderpool’s neighbor “reported him for the crime of being black in Oregon, and Judge Thomas Nelson gave him thirty days to leave the territory.”

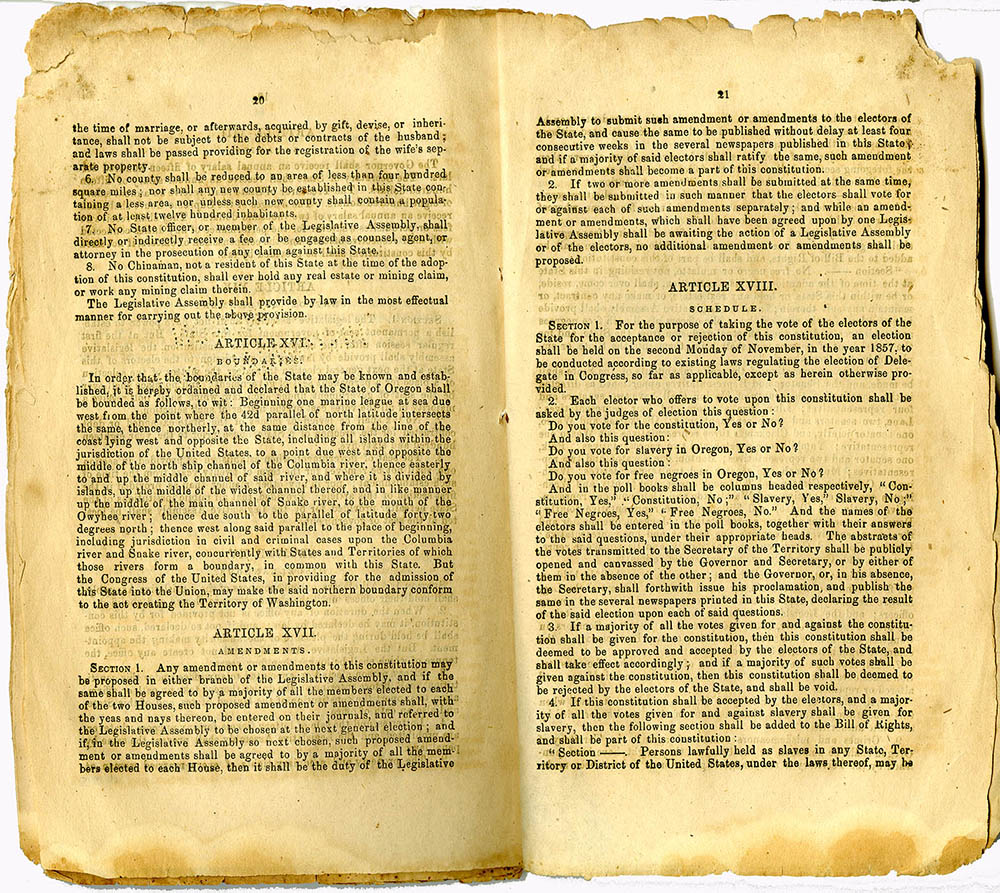

In 1857, as Oregon sought to become a state, it wrote the exclusion of blacks into its constitution: “No free negro or mulatto, not residing in this State at the time of the adoption of this constitution, shall ever come, reside, or be within this State, or hold any real estate, or make any contract, or maintain any suit therein; and the Legislative Assembly shall provide by penal laws for the removal by public officers of all such free negroes and mulattoes, and for their effectual exclusion from the State, and for the punishment of persons who shall bring them into the State, or employ or harbor them therein.”

When Oregon entered the Union in 1859 — it did so as a “whites-only” state. The original state constitution banned slavery but also excluded nonwhites from living there.

“Oregon is the only state in the United States that actually began as literally whites-only,” said Winston Grady-Willis, director of Portland State University’s School of Gender, Race, and Nations. “Even though there was subsequent legislation that challenged those statutes, the statutes were not removed from the books until 1922.”

Grady-Willis added: “It’s really important for folks to understand this notion of Oregon as this lily-white state sets the tone and is important structurally for the remainder of the history of not only the state but cities like Portland as well.”

Portland’s reputation as a progressive city is largely a myth, he said. Portland remains the whitest, large city in the United States. According to a July 2015 Census report, the city of 612,206 people, was 77.6 percent white; and 5.8 percent black. Grady-Willis called it “a key site for Klan activity.”

This is the historical backdrop for the charges against Christian, 35, who allegedly verbally abused two women on the train, including one wearing a hijab, and then attacked the men who came to their aid.

During a brief court hearing Tuesday, Christian was unapologetic:

“You call it terrorism,” Christian said in court. “I call it patriotism.”

Oregon has a defiant history of resisting federal laws that gave black people rights.

Karen Gibson, associate professor in Portland State’s Toulan School of Urban Studies and Planning, said Oregon rescinded its initial ratification of the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which granted citizenship to “all persons born or naturalized in the United States,” including former slaves.

Oregon was one of just six states that refused to ratify the 15th Amendment, which gave black men the right to vote.

Oregon did not ratify the 15th amendment until 1959 — one hundred years after the state joined the Union. It was a symbolic adoption as part of its centennial celebration. It did not re-ratify the 14th amendment until 1973.

“Many of the white settlers who came here came for the Oregon Land Donation Act. This place was intentionally settled by whites for whites,” Gibson said.

“They did not want slavery here. They didn’t want land taken over by large plantations so they didn’t have to compete with bonded labor. But they also thought blacks were inferior. That is still here. White supremacy is about that: the beliefs that whites were supreme.”

Darrell Millner, professor emeritus in Portland State’s Black Studies Department, said many early Oregon settlers were opposed to slavery “not because of what it did to blacks but because of what it did to them. Slavery represented a competition they did not wish to work against.”

Millner said Oregon became a place where “many practices we associate with the Jim Crow South were legal here.” In the 1920s, Oregon had the largest Ku Klux Klan organization west of the Mississippi River. In 1922, Walter Pierce, a member of the Ku Klux Klan, was elected governor of Oregon. Pierce served as a member of the U.S. House of Representatives from 1932 to 1942.

Oregon’s hostility toward blacks remains part of the state’s culture.

“In the 1980s and ’90s, Oregon became a destination for the largest skinhead movement in the country,” Millner said. “Their objective was to achieve something pioneers tried to achieve here and that was to create a white homeland.” Millner said that in the 1980s and 1990s, “in Oregon and especially in Portland, it was very dangerous to be a person of color.

An infamous racial attack occurred in Portland in 1988 when an Ethiopian immigrant was fatally beaten by three white supremacist skinheads on the streets of Portland. Mulugeta Seraw was a student at Portland State University. He was killed by three white supremacists who were members of the White Aryan Resistance who beat him with a baseball bat.

In 1990, the Southern Poverty Law Center and the Anti-Defamation League won a lawsuit against the White Aryan Resistance on behalf of Seraw’s family.

Millner said he has lived in Oregon for 47 years. When he heard about the stabbings on the train last month he said he was disturbed but not surprised.

“It reinforced the subterranean awareness all people of color in Oregon have that something like that could happen to them at any time and in place,” he said. “That is reflective of what people of color in Oregon live with. It is on a subconscious level daily. You are constantly aware that is a possibility.”