Lincoln signed a bill in 1862 that paid up to $300 for every enslaved person freed.

By Tera W. Hunter

Dr. Hunter, a professor of American history and African-American studies, specializes in the 19th and 20th centuries.

On April 16, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln signed a bill emancipating enslaved people in Washington, the end of a long struggle. But to ease slaveowners’ pain, the District of Columbia Emancipation Act paid those loyal to the Union up to $300 for every enslaved person freed.

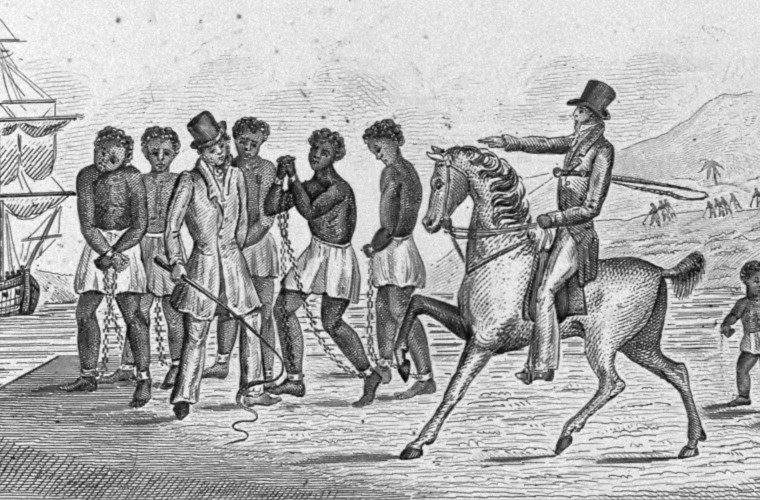

That’s right, slaveowners got reparations. Enslaved African-Americans got nothing for their generations of stolen bodies, snatched children, and expropriated labor other than their mere release from legal bondage.

The compensation clause is not likely to be celebrated today. But as the debate about reparations for slavery intensifies, it is important to remember that slaveowners, far more than enslaved people, were always the primary beneficiaries of public largess.

The act is notable because it was the first time that the federal government authorized abolition of slavery, which hastened its demise in Virginia and Maryland as runaways from these states fled to Washington. It offered concrete proof to enslaved people and their allies that the federal government might facilitate the destruction of slavery everywhere. And it confirmed the worst fears of their foes about an interloping tyrannical president.

Abraham Lincoln, however, was anxious to preserve his fragile alliance with loyal slaveholders. He had advocated abolition of slavery in Washington in 1849 as a congressman, to no avail. As president, he encouraged the border states to voluntarily end slavery. He chose Delaware as an ideal place to take the lead in late 1861. But it became clear that Union slaveowners could not be so easily persuaded. This reinforced the need to make congressional emancipation conditioned on compensating them, which put abolitionists in a bind.

They welcomed the end of slavery in the capital, but chafed at payments that validated the right to own property in the form of human beings. “If compensation is to be given at all,” the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison said at the National Anti-Slavery Convention in Philadelphia in 1833, “it should be given to the outraged and guiltless slaves, and not to those who have plundered and abused them.”

Moderate antislavery advocates like Lincoln did not agree. To the contrary, they believed that any manumission plan had to placate property rights that were buttressed by the Fifth Amendment, which required “just compensation” for government seizure of private assets.

Lincoln appointed a board of commissioners to oversee the process of compensation, headed by the North Carolina abolitionist and New York Times reporter Daniel Reaves Goodloe. The board reviewed more than 1,000 slaveholders’ petitions to claim more than 3,000 enslaved people, close to the entirety of the dwindling population. Most of the petitioners received the full amount allowed. The largest individual payout was $18,000 for 69 slaves.

Although the District of Columbia Emancipation Act marked the only time the federal government would compensate slave owners, there is a long history of slaveowners requesting and receiving indemnification for the loss of their chattel.

After the revolution, as Northern states carried out gradual-emancipation plans, compensation was attractive to slave owners seeking to ease their financial burdens. The 1804 Gradual Abolition Act in New Jersey, for example, did not free anyone immediately. It allowed children of enslaved women to be treated as “apprentices” (slavery by another name) until they reached a certain age and would be freed. The law included a clause that allowed slaveowners to gain compensation by letting their bonds people go free and then reclaiming them as “bound out labor,” which gave them access to state funds for their troubles.

In a break from tradition in the 1850s, the abolitionist Elihu Burritt organized the National Compensated Emancipation Convention in Cleveland to advocate payments to slaveowners, as well as smaller sums to be paid to the people they had enslaved. Nothing came of his dual proposal, however.

To be sure, the major benefactors of slaveowner reparations within the Atlantic slave system were Europeans. When England abolished slavery in its Caribbean colonies, it offered compensation to 46,000 slaveowners at the cost of around $26.2 million.

France went further by penalizing Haiti for the revolution that abolished slavery in its former colony St. Domingue. It levied a huge sum on the island, which crippled it in decades of debt. Former slaves were forced to pay indemnities to former slave owners in exchange for official recognition as the first black independent nation-state in the Western Hemisphere.

The long and insistent coupling of compensation for slaveowners with emancipation is useful for consideration in current debates about reparations for the descendants of the enslaved. Critics and skeptics are fond of saying that enslaved people should have asked for recompense back then. African-Americans did precisely that, going back to the colonial era. They petitioned for “freedom dues,” they sued the estates of former masters for their unrequited toil, and they asked for land to restart their lives as free men and women. Relatively few of those efforts were successful.

An overwhelming majority of white people believed that slaveowners, not enslaved African-Americans, deserved recompense for the benevolence of manumission. The only “reward” that was widely supported was colonization: a trip “back to Africa.” The act allocated $100,000 for the voluntary removal of the newly freed people (at $100 per person) to go to Liberia or Haiti, which rarely happened.

Preserving sacred property rights and moving the Negro problem offshore meant that there was no justice for enslaved African-Americans. All of the candidates running for president must support the federal government’s issuing of reparations to African-Americans who were economically affected by slavery. Justice requires this.

Tera W. Hunter (@TeraWHunter) is a professor of history and African-American studies at Princeton and the author of “Bound in Wedlock: Slave and Free Black Marriage in the Nineteenth Century.”