On the morning of January 25, 1884, Jane Pitts woke up to newspaper headlines that her daughter Helen, without her knowledge, had married the famous abolitionist and writer Frederick Douglass. The news of the union shocked many people, and scrutiny came from all sides at once toward the newlyweds, who now found themselves in the middle of a controversy. Who was Helen Pitts Douglass, and how did her marriage to Frederick become akin to a national scandal?

Born to an upstate New York family whose kin included Franklin D. Roosevelt and Henry David Thoreau, Helen Pitts was raised by abolitionist and reformist parents. After pursuing higher education and obtaining a degree (a rare accomplishment for a woman at that time), she briefly worked as a teacher in Norfolk, Virginia, where a school was opened for Black children soon after the city surrendered to Union forces during the Civil War. Constantly harassed by Confederate sympathizers, Black students in Norfolk faced many barriers to receiving an education. During her tenure, Pitts stood her ground and defended her students, causing whoever harassed them to be arrested and fined for their behavior. Unfortunately, her teaching career was cut short by an illness that forced her to stay bedridden for years.

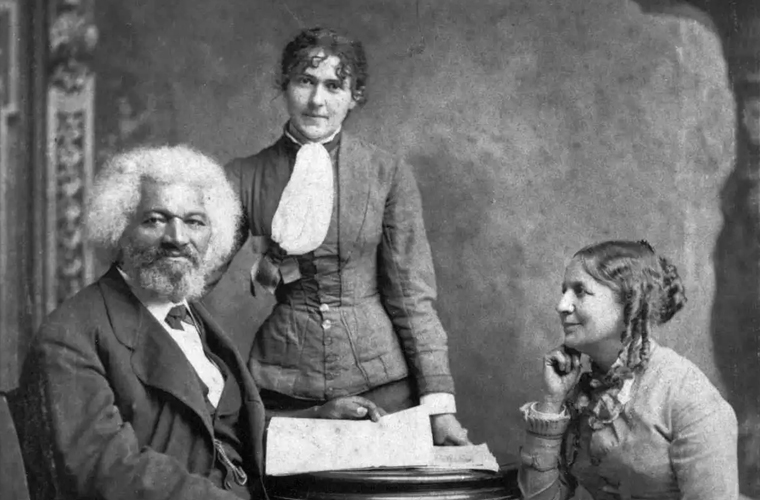

In 1882 Pitts moved to Washington, D.C., where she wrote regularly for The Alpha, a feminist newspaper. She stayed at her uncle’s house, which happened to be next to Cedar Hill, the home of Frederick Douglass and his wife, Anna Murray Douglass. Pitts and Frederick became acquaintances through letters in which they discussed politics with each other. After he was appointed Washington’s recorder of deeds, Pitts was hired as a clerk at his office. It was in that year that his wife of more than 40 years passed away. Douglass subsequently fell into a deep depression, during which he moved north to reconnect with friends, including Pitts’s family. His relationship with Pitts intensified probably sometime in 1883 when they found themselves in each other’s company discussing shared interests, from political reform to theatre. In January 1884, in a surprising move that not even their own families saw coming, Frederick Douglass and Helen Pitts married in the home of a mutual friend.

The immediate reaction from their families was unfavorable, to say the least. Douglass’s children opposed the marriage because they saw it as an insult to their mother, who had passed away about 18 months earlier. Pitts’s family, though devout abolitionists, did not accept her decision as a white woman to marry a Black man. Her father, Gideon Pitts, refused to talk to her again and excluded her from his will.

Around the country, responses to the marriage tended to be negative. Many national publications targeted the newlyweds’ age gap, mistakenly stating that Helen was younger than Frederick’s eldest child. In reality, Helen and Frederick were 21 years apart. Criticisms from both white people and Black people targeted the interracial nature of the marriage. Interracial marriage, especially between a Black man and a white woman, was controversial and rare in America’s predominantly white society. Black publications implied that Douglass was betraying his race and his cause by marrying a white woman. Despite the negative press, some influential activists and friends of his, such as journalist Ida B. Wells, spoke in defense of the couple. Although Frederick and Helen mostly refused to respond to the criticism, Frederick, in a letter to a friend in 1884, asked, “What business has the world with the color of my wife?”

Frederick Douglass and Helen Pitts Douglass remained married until his death in 1895. After his will was contested by his children, Helen secured loans in order to buy Cedar Hill and preserve it as a memorial to her late husband. She dedicated the rest of her life to commemorating Frederick Douglass’s legacy as well as giving speeches about ongoing political issues. Because of her perseverance, Cedar Hill is now a national historic site where visitors can see original furnishings in the home that she and Frederick Douglass lived and worked in.