Sojourner Truth was outraged, but her feelings didn’t show in a letter she wrote about her meeting with Abraham Lincoln in October 1864. She’d gone to Lincoln to call his attention to the conditions at settlements for former slaves, including one called Freedman’s Village, where she asked to be appointed as a counselor. “I was never treated with more kindness and cordiality,” she wrote to a fellow abolitionist of her meeting with the president. Lincoln granted her request to work at the camp, and Truth lived there for a year, preaching and otherwise advocating for the people who lived there.

Freedman’s Village, which started in 1863 with 50 wooden houses, was touted as a model community when it was dedicated, with farms, a hospital, an orphanage, and a home for the elderly. By 1864, though, conditions were dismal. People were hungry, unwanted by the surrounding community, and exploited by opportunists. “I am a going around among the colored folks and find out who it is selling the clothing to them that is sent to them from the North,” Truth wrote to her daughter, deeply dismayed, shortly before her meeting with Lincoln.

Through the work of Truth and missionary organizations, the camp became a permanent home for former slaves. That home lasted until 1890 when it was razed—residents driven from their homes—to make way for Arlington National Cemetery.

Freedman’s Village was built on land seized from Robert E. Lee and occupied by the Union army since the beginning of the war. The grounds of the Confederate commander’s estate were used first as a soldier’s camp then as a graveyard, in a deliberate attempt to provoke the general. It worked. “Your old home, if not destroyed by our enemies, has been so desecrated that I cannot bear to think of it,” Lee wrote in a letter to his daughter in a Christmastime letter in 1861.

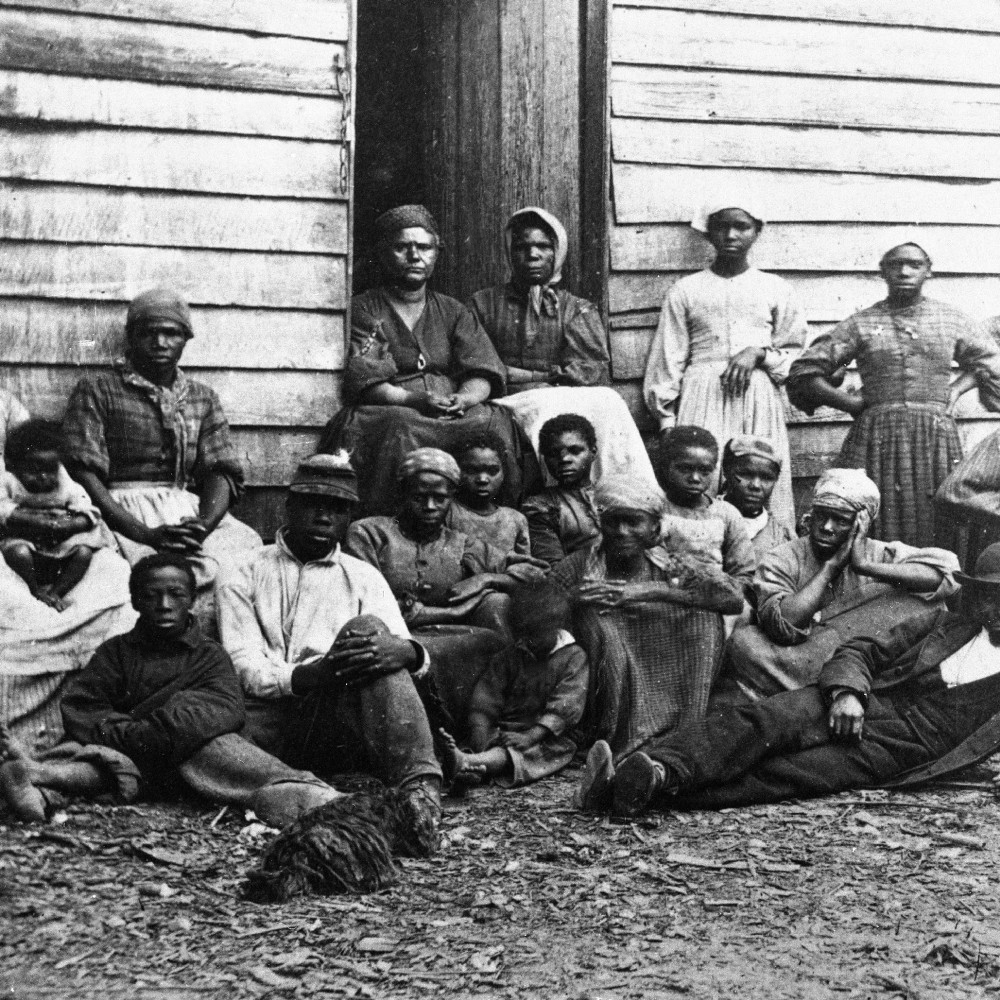

By 1863, the land was home to former slaves who escaped to the capital during the Civil War. Slavery had been abolished in Washington D.C. in 1862, attracting thousands running from bondage, dubbed “contraband” because they were still considered property of their Southern owners. So-called “contraband camps” were established to house them.

Freedman’s Village, which began with 100 inhabitants, was one of them. It was dedicated to a ceremony in December of 1863 that featured speeches from Congressmen and cabinet members. Cannons boomed to mark the occasion, and the mood was hopeful, notes historian Rick Beard. Schoolchildren even memorized this chant: “To Freedomsville we soon shall go/ And there still let the people know/That we have minds that do expand/Beyond the scope of ‘Contraband.’”

A year later in 1864, when Truth decided to take matters into her own hands by meeting with the president, about 3,000 people lived in the village. And conditions were difficult. Residents said the white man who directed the village was as bad as any Southern overseer, and the complaints, including allegations of beatings from soldiers who patrolled the camps, were taken seriously enough to be investigated by federal agencies. The roads were rutted and the stoves used to heat the home for the elderly didn’t work, even though residents paid rent on top of a penalty called a “contraband tax” for their upkeep.

Still, people had homes. They lived with their families. Many worked in the village, on farms that fed residents, or in the surrounding area. They made improvements to their homes and sent their children to schools, and everyday life that was beyond fantasy before emancipation.

But active efforts to evict people from Freedman Village started in 1868. Residents won that first battle, and the government allowed them to stay for another two years, but more than 150 elderly people were forced to leave (they were taken in by Freedman’s Hospital). The efforts grew more concerted in 1882 when local government officials and business leaders embraced the federal government’s plans for the land as a public park. Locals had been framing the village as a problem for years, with allegations ranging from unauthorized tree cutting to using up more than their fair share of relief funds. The war department ordered the people of Freedman’s Village to leave in 1886. Representatives of the village pleaded for $350 per resident to offset the costs of the forced relocations. They didn’t get it. By the 1890s, the government had destroyed all the remaining houses.

Reparations of $75,000, awarded in 1900, were eventually divided among former residents of the village and their heirs. That sum was dwarfed, though, by the amount paid to Robert E. Lee’s eldest son for his family estate. In a case that made it all the way to the Supreme Court, he was awarded the title to the lands and sold it back to the federal government for $150,000, about $3.7 million in today’s dollars.

The land eventually became Arlington National Cemetery, where some of the most famous American veterans are buried, including both Robert F. and John F. Kennedy. Prominent African Americans like Medgar Evers, Thurgood Marshall, and Joe Louis are also there. But so are 3,800 former contrabands from the Civil War, with markers engraved with only with “citizen” or “civilian.”