The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), founded in 1942, became one of the leading activist organizations in the early years of the American civil rights movement. In the early 1960s, CORE, working with other civil rights groups, launched a series of initiatives: the Freedom Rides, aimed at desegregating public facilities, the Freedom Summer voter registration project, and the historic 1963 March on Washington. CORE initially embraced a pacifist, non-violent approach to fighting racial segregation, but by the late 1960s, the group’s leadership had shifted its focus towards the political ideology of black nationalism and separatism.

The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) was founded on the University of Chicago campus in 1942 as an outgrowth of the pacifist Fellowship of Reconciliation. For the next two decades, CORE introduced a small group of civil rights activists to the idea of achieving change through nonviolence, but during these years, its chapters were all in the North and its membership was predominantly white and middle class. In 1955 CORE went into the South and provided nonviolence training to demonstrators during the Montgomery, Alabama, bus boycott. Soon thereafter, CORE hired a small staff to work in the South.

Did you know? In June 1964, three CORE activists, Andrew Goodman, James Chaney, and Michael Schwerner, were murdered by members of the Ku Klux Klan while working as volunteers for CORE’s Freedom Summer voter registration project in Mississippi. The group first drew national attention in 1960 with its active support of the sit-in movement at lunch counters that refused to serve blacks. Symbolic of the organization’s new direction was the appointment in February 1961 of James Farmer, as CORE’s first black national director.

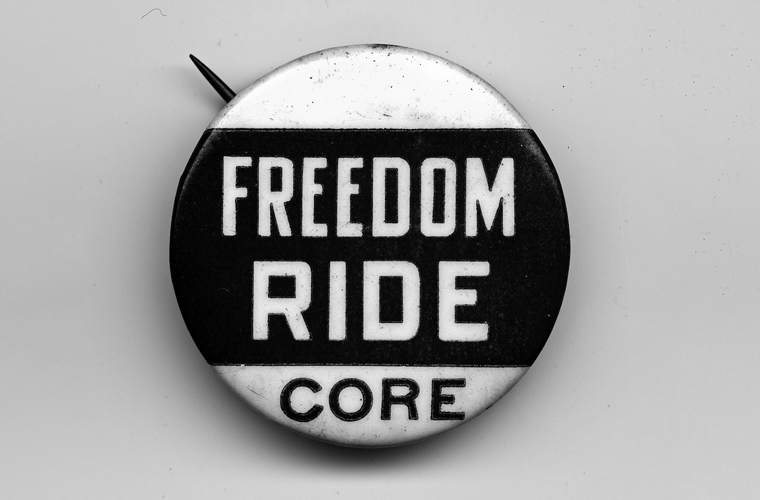

A few months later, CORE organized the first Freedom Ride to desegregate interstate transportation facilities. Although the riders were attacked so brutally in Alabama that they were unable to continue, more than a thousand participants, black and white, carried on Freedom Rides during the summer.

Starting in late 1961, voter registration became the new civil rights priority, and CORE focused on Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina. At this time many civil rights workers were beginning to feel that black political power, not integration, offered the best hope for achieving racial equality. Although CORE did not abandon its commitment to racial understanding–it was, for instance, a cosponsor of the March on Washington in August 1963–it placed increasing emphasis on black autonomy.

Pessimism about integration was reinforced by the wave of beatings and murders that met the voter registration projects and by CORE’s expanded work in the North, which shed new light on the depth and intransigence of racial discrimination in the United States.

In early 1966, Farmer, a pacifist and longtime advocate of racial integration, was replaced as national director by Floyd McKissick, who had become committed to black separatism. Thereafter, as a primarily black organization, CORE continued to press for political and economic justice for blacks while also lending its voice to the rising antiwar movement.