Hubert Harrison is one of the important figures of twentieth-century African-American history. Fondly known as “the Black Socrates,” a title bestowed on him by John G. Jackson of American Atheists, he ran newspapers and political organizations, fostered activists and artists, decried racial injustice in articles and essays and called out black leaders for toadying to white patrons or espousing elitism. Historian Joel A. Rogers described Harrison as “the foremost Afro-American intellect of his time” in his book, World’s Great Men of Color.

Harrison was born in St. Croix, the Virgin Islands, then a Danish colony, on April 27, 1883, to a Bajan mother and a Crucian father. His mother died in 1900 when Harrison was only seventeen years old. His dad had died earlier and he left the Caribbean and arrived in New York as an orphan in 1900. He got a night school secondary diploma. Apart from this, all other academic training came from himself, augmented by self-confidence forged in the West Indies amid a history of slave rebellion, labor protests, and marginal white hegemony.

As a newbie in the States, Harrison was shocked by the treatment black people received. These included the epidemic lynchings, Jim Crow, and disenfranchisement of black voters. These were against the life he was used to in St. Croix where literacy was high and residents of African or mixed descent often had middle-class jobs. This trigged his activism and the start of his bold push for equal rights.

In 1917, Harrison founded The Voice, a weekly which reached an estimated 55,000 readers at a time when New York City was home to 60,000 African Americans. The paper was a broadsheet advocating black empowerment and debate but also carried book reviews and poetry. It was printed on pink paper which made it recognizable even to illiterates. The paper’s success did not last because Harrison refused to carry ads for skin lighteners and hair straighteners and his revenues shrank.

A year later, he created the Liberty League to champion federal anti-lynching legislation and urged black solidarity and self-defense—if necessary, armed. The militancy part of the league was opposed by The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. This caused Harrison to harshly criticize his fellow blacks with the statement: they had “a wish-bone where their backbone ought to have been.”

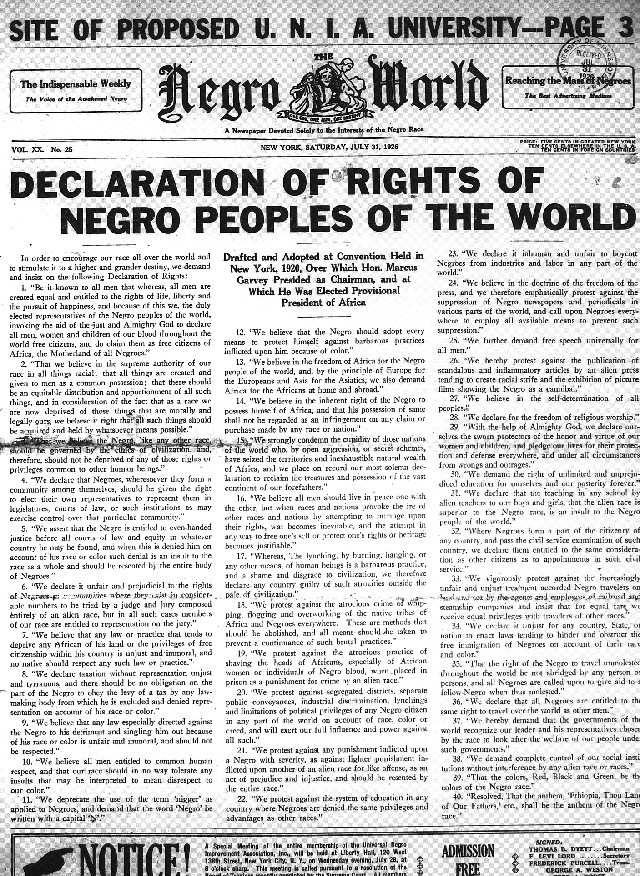

This is not the first time Harrison had a falling out with other black activists or organizations. He is known to have scorned W.E.B. DuBois’s “Talented Tenth” as the “Subsidized Sixth”. In 1910, challenging Booker T. Washington’s assertions about opportunities for blacks in the South, he published a letter in the New York Sun rebutting Washington’s optimism with hard data on harsh racial disparities. In response, allies of Washington at the Post Office where Harrison worked at the time claimed he was a slacker and he lost his job. He also edited Negro World, a weekly published by Marcus Garvey until the two fell out.

He also edited Negro World, a weekly published by Marcus Garvey until the two fell out.

He also edited Negro World, a weekly published by Marcus Garvey until the two fell out.

On the political front, Harrison joined the Socialist Party in 1911 where he worked as an organizer for two years. He was the only black speaker to address the Paterson Silk Strike in 1913 when workers seeking an eight-hour day and better conditions walked out of a New Jersey fabric mill. Harrison left the Socialist Party which hesitated to organize blacks and provided only desultory support. In 1924, Harrison established the Liberty Party, which focused on international black political organization.

Hubert Harrison, seated at left, and International Workers of the World leaders Elizabeth Gurley Flynn and Bill Haywood, seated right, organized the 1913 Paterson Silk Strike

Hubert Harrison, seated at left, and International Workers of the World leaders Elizabeth Gurley Flynn and Bill Haywood, seated right, organized the 1913 Paterson Silk Strike

Harrison became an American citizen in 1922. He was married albeit briefly due to children and marital issues. The great orator gave several lectures, stressing the value of education. He is quoted to have told the listener, “Remember always that the best college is that on your bookshelf. The best education is on the inside of your head”.

Novelist Henry Miller, then a young socialist said about Harrison, “With a few well-directed words he had the ability to demolish any opponent. He did it neatly and smoothly too, `with kid gloves,’ so to speak. I described the wonderful way he smiled, his easy assurance, the great sculptured head which he carried on his shoulders like a lion . . .”

Rogers adds that “No one worked more seriously and indefatigably to enlighten” others and “none of the Afro-American leaders of his time had a saner and more effective program.”

Labor and civil rights leader A. Philip Randolph described Harrison as “the father of Harlem Radicalism.” Harrison’s friend and pallbearer, Arthur Schomburg, fully aware of his popularity, eulogized to the thousands attending Harrison’s Harlem funeral that he was also “ahead of his time.”

Struck by appendicitis in 1927, Harrison, 43, died in surgery. He was buried in an unmarked grave in the Bronx.

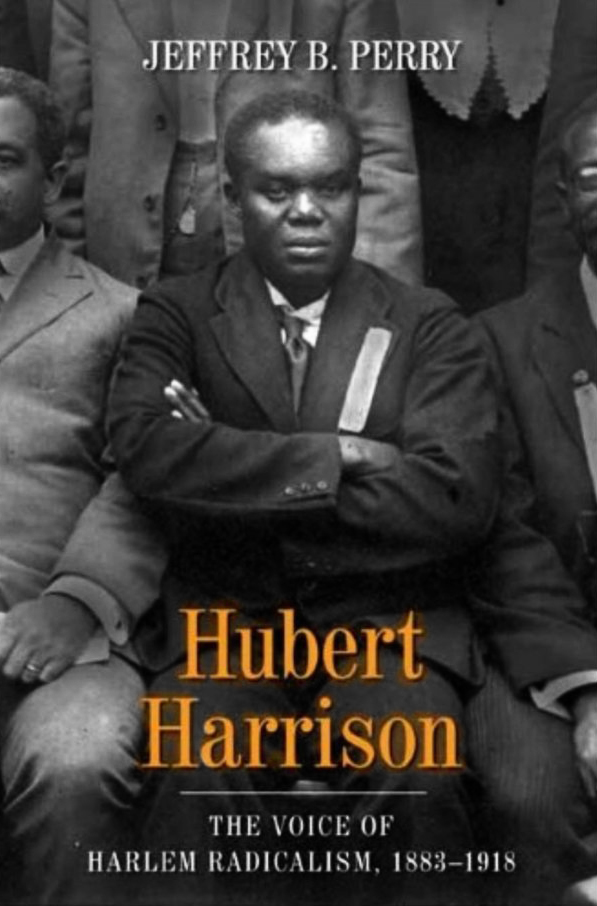

His remarkable life is captured in a book by Jeffrey Perry (published in 2009) titled Hubert Harrison: The Voice of Harlem Radicalism, 1883—1918.

Hubert Harrison: The Voice of Harlem Radicalism, 1883—1918.

Hubert Harrison: The Voice of Harlem Radicalism, 1883—1918.