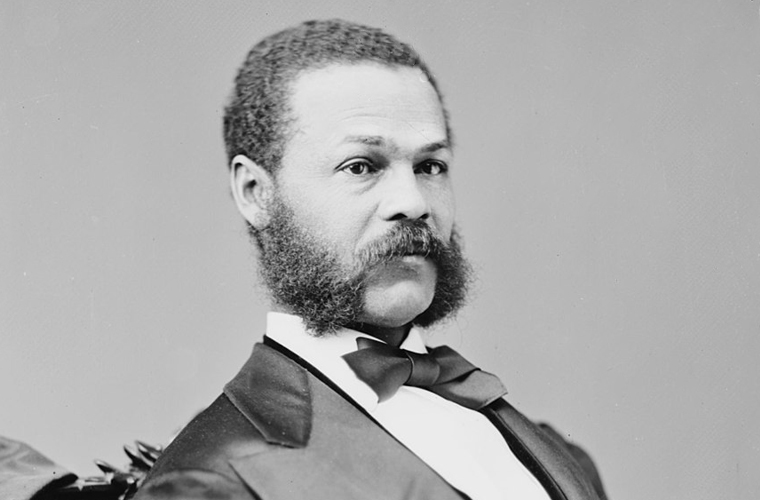

Jefferson Franklin Long was Georgia’s first African American congressman and the first black member to speak on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives.

Long was born into slavery on March 3, 1836, in Alabama to an enslaved mother and a white father. By the 1840 U.S. census, he was listed as a slave in the household of James C. Loyd, a tailor with modest land holdings in Knoxville, in Crawford County, Georgia. During the 1850s the Loyd family moved from Knoxville to Macon, taking Long with them. Not long after their arrival, they sold Long to Edwin Saulsbury, a prominent businessman.

Long had taken well to the tailor trade and was soon set up in a shop by his new owner. The slave trade was alive and well in Macon, and Long had a front-row seat—his shop was across the street from the slave auction block. Fortunately for him, the shop was also next door to the local newspaper. When Long was not employed mending or sewing, he was beseeching the typesetters at the newspaper to set copy, an activity he observed closely as he taught himself to read and write. By 1860 Long had married Lucinda Carhart and had started a family.

By the end of the Civil War (1861-65), Long was a flourishing member of society. He was established in his own shop and was an active member of the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME) of Macon, headed by Henry McNeal Turner. Under Turner’s influence Long made his first political appearance at a meeting of the Georgia Educational Association in 1867. Long may also have had a hand in the establishment of Georgia’s Freedman’s Savings Bank, a project led by Turner and established through the AME Church.

Long became a prominent member of the Republican Party in 1867 and was appointed as one of the party’s key speakers and political organizers. He traveled throughout Georgia and much of the South, praising the passage of the Congressional Reconstruction Act of 1867 and urging former slaves to register to vote. Partially as a result of his efforts, thirty-seven African Americans were elected to the Georgia constitutional convention of 1867 and thirty-two to the state legislature, among them Turner. Long spent much of his free time working to better the living conditions of his fellow man by organizing conventions that advocated public education, higher wages, and better terms for tenant farmers, or sharecroppers. He also helped organize the Union Brotherhood Lodge, a black mutual aid society, in Macon.

In December 1870 Long became Georgia’s first African American congressman when he was elected to fill a vacancy in the 41st Congress. Prior to Long’s election, Georgia’s representatives had been dismissed by Congress after the state legislature failed to ratify the Fifteenth Amendment. Once Georgia met Congress’s conditions for readmission, a delegation from the state was permitted to return for the remainder of the congressional session. However, Georgia’s representatives elected in 1867 were rejected once again because they were eligible to serve in the 40th Congress but not the 41st. The situation left Georgia without representation in Congress from March 1869 until December 1870. Elections for the 41st and 42nd sessions were held simultaneously on December 20, 1870, with the Republican Party elevating black candidates for the abbreviated session while reserving the full term for white candidates. Long served from January 16, 1871, until the end of the session on March 3.

During his term in Congress, Long made history yet again when, on February 1, 1871, he became the first African American member to speak on the floor of the House of Representatives. An amnesty bill that would modify the oath required of former Confederates who sought public office had passed the Senate and was to be voted on by the House. Opposed to the measure, Long asked the assembly, “Do we, then, really propose here to-day, when the country is not ready for it, . . . when loyal men dare not carry the ‘stars and stripes’ through our streets, for if they do they will be turned out of employment, to relieve from political disability the very men who have committed these Kuklux outrages?” Nonetheless, the bill passed later that day by a vote of 118 to 90.

As Reconstruction ended and the freedoms he had fought so hard for began to dwindle, Long became disenchanted with the political system. On election day in 1872, he rallied black voters and marched with them to the polls in Macon, where they were met by a group of armed whites. In the ensuing riot, at least three people were killed, and most black voters fled before casting a ballot.

Long never again held public office. He remained loyal to the radical wing of the Republican Party and served as a delegate to the national conventions through 1880, but the party was divided. The Bourbon Democrats had reclaimed the South, and Long began to realize that the only way to regain any of the ground blacks had lost was to organize an independent African American voting bloc. In 1880 Long put his theory into practice and supported Governor Alfred H. Colquitt, a member of the Bourbon Triumvirate, in his reelection campaign. With the support of the black Republican vote, Colquitt defeated his Democratic opponent, Thomas Norwood. White Democrats were split between Colquitt and Norwood, and white Republicans supported Norwood. (The Republican Party had failed to offer its own candidate.) Thus, Long successfully demonstrated that the black vote could be significant when whites were divided.

By 1884, however, African Americans had lost nearly all their power in the Republican Party and were no longer influential in state politics. Disillusioned, Long retreated from politics. He lived out the rest of his life as a private citizen, operating several businesses, including the first dry-cleaning establishment in Macon. He was not a rich man, but he owned property and managed to educate all six of his children. What free time he had was spent in his library, book in hand. Long died from influenza on February 4, 1901, and was buried in Macon’s Linwood Cemetery.

Long remained the only African American to represent Georgia in the House of Representatives until the election of Andrew Young in 1972.