Often referred to as the unofficial mayor of Auburn Avenue, John Wesley Dobbs was one of several distinguished African American civic and political leaders who worked to achieve racial equality in segregated Atlanta during the first half of the twentieth century.

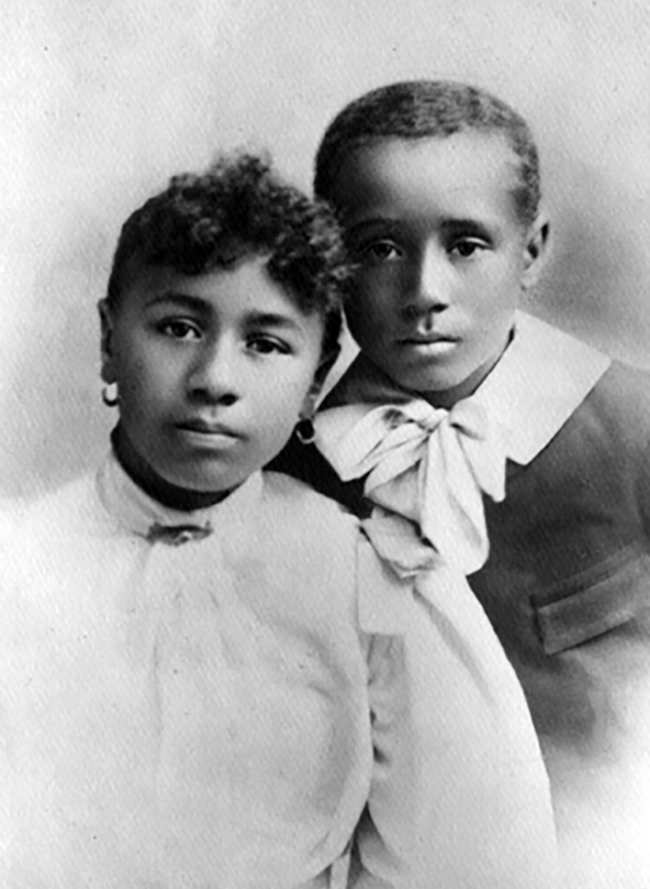

Born in Marietta in 1882 to Minnie and Will Dobbs, John Wesley Dobbs grew up in poverty on a farm near Kennesaw. Two years after his birth his mother and father separated. His mother moved to Savannah to work in the home of a white family there, leaving Dobbs and his sister in the care of his grandparents and various other relatives. Minnie saw her children regularly, though, and in 1891 they moved to Savannah to live with her.

In Savannah Dobbs attended school full-time for the first time. His formal education nearly ended after fifth grade because of his family’s financial difficulties, but a white woman intervened and offered Dobbs a job that would not interfere with his school attendance. While still in grammar school, Dobbs also shined shoes and delivered newspapers to supplement the family income.

In 1897, at the age of fifteen, Dobbs moved to Atlanta, where he continued his education at Atlanta Baptist College (later Morehouse College). His mother’s ill health forced Dobbs to drop out of school and return to Savannah to care for her. He never earned a college degree. He continued his studies independently, however, and passed a civil service exam that in 1903 allowed him to become a railway mail clerk for the U.S. Post Office in Atlanta. (Dobbs in fact would never stop studying, reading voraciously during his spare time.) Dobbs held his position at the post office, a well-respected one within the Black community, for thirty-two years.

In 1906 Dobbs married Irene Ophelia Thompson, with whom he had six daughters, all of whom went on to become graduates of Spelman College in Atlanta. Mattiwilda Dobbs, his fifth daughter, became an acclaimed opera singer. Dobbs worked to instill in his children a sense of self-worth and a desire to succeed. He forbade them to attend segregated events and constantly reminded them of their equality. Additionally, he traveled with his family extensively to broaden their range of experience.

In 1911 Dobbs was initiated into the Prince Hall Masons, a fraternal order that attracted socially conscious leaders within the Black middle class. Dobbs was elected Grand Master of the Prince Hall Masons of Georgia in 1932, thereby earning the nickname “the Grand.” Through his leadership position with the Masons, he tried to instill in Atlanta’s African American community those same values he worked to pass on to his children.

Dobbs fervently believed that African American suffrage was the key to racial advancement. He announced a goal of registering 10,000 Black voters in Atlanta and preached the importance of voter registration in Masonic halls, in African American churches, and on street corners. Dobbs also founded the Atlanta Civic and Political League in 1936 and, with attorney A. T. Walden, cofounded the Atlanta Negro Voters League in 1946. Both of these leagues advocated voter registration and Black political unity.

Due largely to Dobbs’s efforts, African Americans achieved two significant political victories in the late 1940s. In the spring of 1948 Atlanta mayor William B. Hartsfield fulfilled a promise he had made to Dobbs by hiring eight African American police officers. Although they could patrol only Black neighborhoods and could not arrest whites, the hiring was a significant challenge to segregation. The following year Hartsfield fulfilled another campaign promise by installing street lamps on Auburn Avenue, the center of Atlanta’s Black community. Both of these achievements served to solidify Dobbs’s position as a leader. (Dobbs himself coined the term “Sweet Auburn,” an expression of the area’s thriving businesses and active social and civic life.)

During the 1950s Dobbs continued his work toward African American equality. He constantly pressed Hartsfield to fulfill other promises made to the Black community. Dobbs’s influence began to wane, though, as the decade ended and a younger generation of African American leaders emerged at the forefront of the civil rights struggle. By this time he was suffering from arthritis, often unable to get out of bed.

Dobbs’s health declined, and on August 21, 1961, he suffered a stroke. He died nine days later, on August 30, 1961, the same day that Atlanta city schools were desegregated. Martin Luther King Jr. was one of the speakers at Dobbs’s funeral, and Thurgood Marshall, head of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and future Supreme Court justice, served as a pallbearer. Dobbs received a lasting tribute on January 10, 1994, when his grandson, Atlanta mayor Maynard Jackson, changed the name of Houston Street to John Wesley Dobbs Avenue.