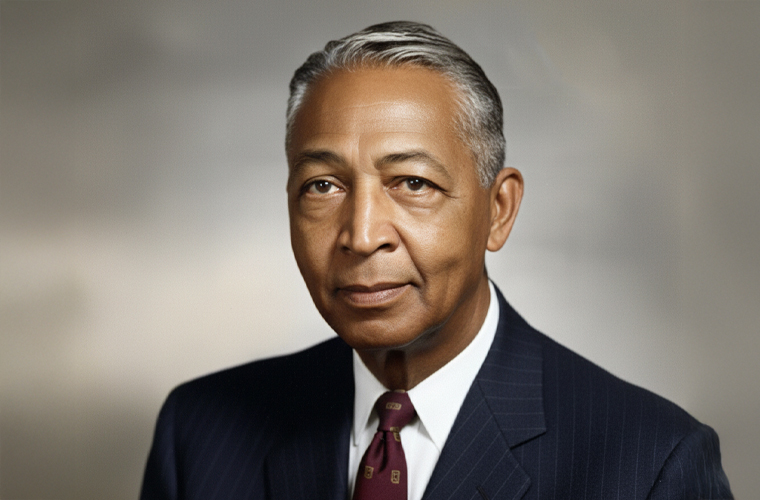

The Unsung Pioneer of Food Preservation

In the annals of American innovation, few names resonate as profoundly in the realm of everyday sustenance as Lloyd Augustus Hall. Born at the turn of the 20th century, Hall was a trailblazing chemist whose ingenuity transformed the way the world stores and savors its food. With over 100 U.S. and foreign patents to his name, he revolutionized meat curing, spice sterilization, and antioxidant applications—methods that remain staples in the global food industry today. Yet, like many African American inventors of his era, Hall’s story is one of quiet perseverance amid systemic barriers, a testament to how brilliance can nourish generations.

Lloyd Augustus Hall entered the world on June 20, 1894, in Elgin, Illinois, a Midwestern town emblematic of the industrial promise and racial tensions of the Gilded Age. His family tree was woven with threads of abolitionist valor and scholarly ambition. His grandmother had escaped slavery via the Underground Railroad, arriving in Illinois at just 16 years old. His grandfather, a pioneering figure, settled in Chicago in 1837 and became the first pastor of Quinn Chapel A.M.E. Church in 1841, one of the earliest Black congregations in the city. Hall’s father, Augustus Hall Sr., was a Baptist minister, and his mother, Isabel, both high school graduates, instilled in him a fierce dedication to education.

Raised in nearby Aurora, Illinois, young Lloyd was a prodigy of both mind and body. He captained his high school’s speech and debate team while starring in football, track, and baseball—prowess that secured scholarships from four universities. In 1912, he graduated from East Side High School and enrolled at Northwestern University in Chicago, where he pursued pharmaceutical chemistry. There, he not only earned a Bachelor of Science in 1914 and a master’s degree in 1916 but also forged a pivotal connection with Carroll L. Griffith, whose family owned the food-processing firm Griffith Laboratories—a relationship that would shape his destiny. Hall later received a doctorate from Virginia State College in 1944, capping a lifetime of academic rigor.

Career Beginnings: Triumph Over Adversity

Hall’s entry into the professional world was a stark collision with America’s racial realities. Fresh from graduate school, he aced a phone interview for a chemist position at Western Electric Company—only to be turned away at the door upon revealing he was Black. Undeterred, he pivoted to public service as a senior sanitary chemist for Chicago’s Department of Health, honing his skills in food safety during an era when contamination scandals plagued urban markets.

World War I interrupted his trajectory, drawing him into the U.S. Ordnance Department as chief inspector of powder and explosives—a role demanding precision under pressure. Post-war, Hall married Myrrhene Newsome in 1919, and the couple settled in Chicago. He ascended quickly: chief chemist at John Morrell Co., a major meatpacker; president and chemical director at Boyer Chemical Laboratory; and founder of Chemical Products Corporation. In 1925, at Griffith Laboratories, he found his enduring platform as chief chemist and director of research, a post he held for 34 years until retiring in 1959. There, amid the hum of industrial mixers and the sharp tang of curing salts, Hall’s genius flourished.

Inventions: Safeguarding the Plate

Hall’s crowning achievements addressed the perennial scourge of food spoilage, a problem that wasted fortunes and imperiled health in the pre-refrigeration boom. Before his interventions, meat preservation leaned on crude salts laced with potassium nitrate, yielding bitter flavors and structural weaknesses that caused cuts to crumble during slicing.

In 1932, Hall patented a breakthrough: “flash-drying,” a process blending sodium chloride with microscopic crystals of sodium nitrate and nitrite (U.S. Patent No. 2,107,697). By evaporating the mixture over heated rollers, he created uniform, quick-dissolving salts that evenly penetrated meat, suppressing the botulism-causing nitrogen while preserving tenderness and taste. This curing method—still the gold standard in bacon, ham, and sausages—slashes spoilage risks without the acrid bite of old techniques.

Hall didn’t stop at meats. He pioneered antioxidants like lecithin, propyl gallate, and ascorbyl palmitate to shield bakery fats and oils from oxygen’s corrosive kiss, preventing rancidity in everything from cookies to canned goods. Challenging folklore that spices like cloves and ginger warded off decay, Hall proved they often harbored bacteria and molds, hastening rot. His riposte? The Ethylene Oxide Vacugas process: exposing spices to ethylene oxide gas in a vacuum chamber to eradicate microbes without altering flavor or hue—a technique now vital for sterilizing pharmaceuticals and cosmetics too.

Across his career, Hall amassed 59 U.S. patents alone, many focused on these preservation pillars, ensuring safer, longer-lasting provisions for a hungry world.

Legacy: A Global Feast of Impact

Retirement freed Hall for broader service. From 1962 to 1964, President John F. Kennedy appointed him to the American Food for Peace Council, where he orchestrated aid shipments to famine-struck nations. He consulted for the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization until his death on January 2, 1971, in Pasadena, California, at age 76. Honors poured in posthumously: honorary doctorates from Virginia State, Howard, and Tuskegee universities; induction into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2004; and an honorary lifetime membership from the American Institute of Chemists in 1959.

Today, Hall’s shadow looms large over supermarket aisles. His curing salts underpin the $100 billion U.S. meat industry, while his sterilization savvy bolsters global supply chains. Though modern scrutiny flags nitrite health risks—sparking nitrate-free trends—Hall’s foundational work underscores sustainable innovation’s power. In an age of lab-grown meats and climate-conscious eats, his ethos endures: science as the silent guardian of the table, turning peril into plenty for all.