Racially segregated schools in the United States were educational institutions that practiced the separation of students based on their race or ethnicity. These schools were prevalent primarily in the southern states from the late 19th century until the mid-20th century. The legal basis for racially segregated schools was established by the landmark Supreme Court case Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896. The court’s decision, in that case, established the “separate but equal” doctrine, which allowed for racially segregated public facilities as long as they were deemed to be equal in quality.

However, in 1954, the Supreme Court issued its ruling in the case Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, overturning the “separate but equal” doctrine and declaring that segregated schools were inherently unequal and violated the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause. The decision marked a significant turning point in the civil rights movement and set the stage for desegregation efforts across the country.

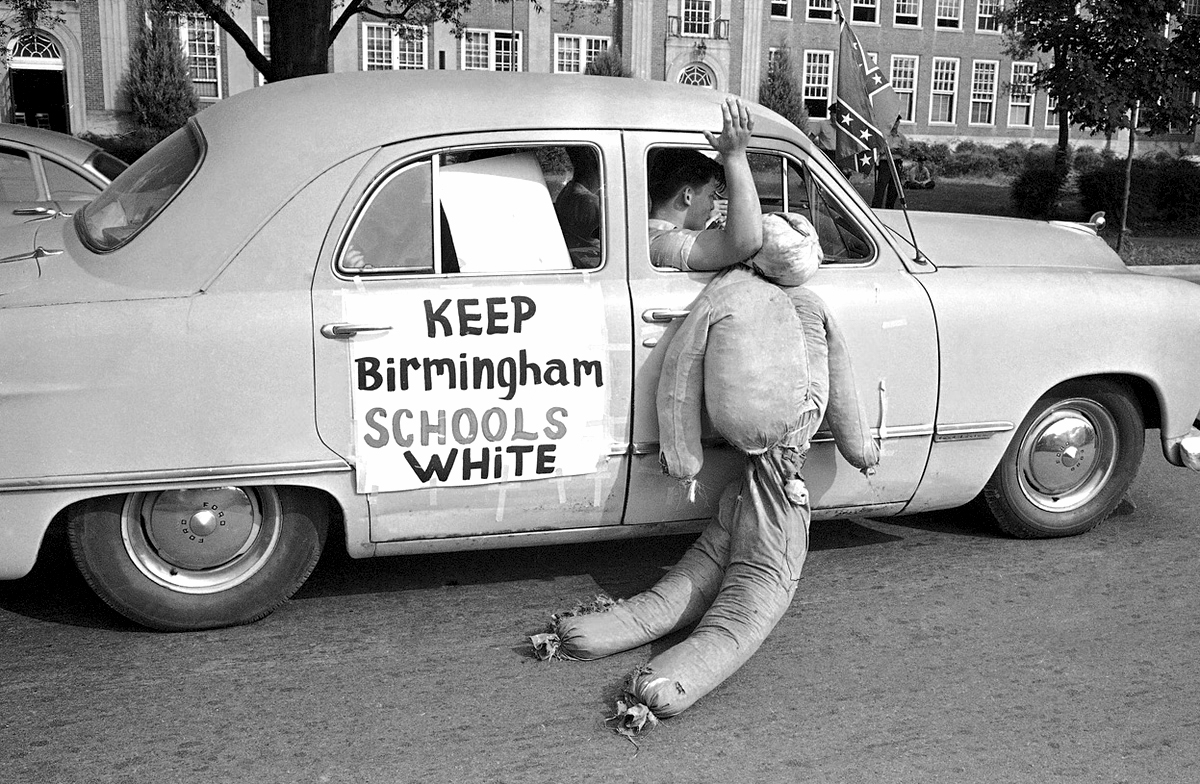

Following the Brown v. Board of Education decision, the process of desegregation was gradual and met with resistance in many areas. Some states, school districts, and local communities resisted desegregation efforts, leading to a period known as “Massive Resistance.” It took several years, court battles, and federal intervention to enforce desegregation and bring about more integrated schools.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and subsequent legislation further supported the desegregation of schools and prohibited discrimination based on race or ethnicity in educational institutions that received federal funding. While significant progress has been made since then, achieving true educational equity and eliminating the effects of historical segregation remains an ongoing challenge in the United States. Efforts to address disparities and promote equal opportunities in education continue to this day.