“Separate but equal” refers to the infamously racist decision by the U.S. Supreme Court in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) that allowed the use of segregation laws by states and local governments. The phrase “separate but equal” comes from a part of the Court’s decision that argued separate rail cars for whites and African Americans were equal at least as required by the Equal Protection Clause. Following this decision, a monumental amount of segregation laws were enacted by state and local governments throughout the country, sparking decades of crude legal and social treatment of African Americans.

The horrid aftermath of “separate but equal” from Ferguson was halted by the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education (1954) where the Court said that separate schools for African American students were “inherently unequal.” While Brown has allowed for desegregation in the United States, the history of “separate but equal” remains an unnerving past for the country and the Supreme Court.

Overview

The decision in Plessy v. Ferguson, mostly known for the introduction of the “separate but equal” doctrine, was rendered on May 18, 1896, by the seven-to-one majority of the U.S. Supreme Court (one Justice did not participate). The case arose out of the incident that took place in 1892 in which Homer Plessy (seven-eighths white and one-eighth black) purchased a train ticket to travel within Louisiana and took a seat in a car reserved for white passengers. After he refused to move to a car for African Americans, he was arrested and charged with violating Louisiana’s Separate Car Act.

The decision in Plessy v. Ferguson was the first major inquiry into the meaning of the equal-protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, which prohibits the states from denying “equal protection of the laws” to any person within their jurisdiction.

In the majority opinion authored by Justice Henry Billings Brown, the Court held that the state law was constitutional. Justice Brown stated that, even though the Fourteenth Amendment intended to establish absolute equality for the races, separate treatment did not imply the inferiority of African Americans. Even though the Court did not specifically use the phrase “separate but equal,” the Court noted that there was no meaningful difference in equality between the white and the black railway cars, creating the doctrine later named “separate but equal.” Implementation of the “separate but equal” doctrine gave constitutional sanction to laws designed to achieve racial segregation by means of separate and equal public facilities and services for African Americans and whites.

The “separate but equal” doctrine introduced by the decision, in this case, was used for assessing the constitutionality of racial segregation laws until 1954 when it was overruled by the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education.

Background

During the Reconstruction, the federal government granted the right to vote to African Americans in the South and provided some equal protection to African American citizens. As Reconstruction failed in 1877 the movement for the rights of African Americans stalled. When whites regained control of southern states, they began to enact laws that oppressed African Americans through segregation (known as Jim Crow Laws). Enforced by criminal penalties, these laws created separate schools, parks, waiting rooms, and other segregated public accommodations.

Although the 1875 Civil Rights Act had stated that all races were entitled to equal treatment in public accommodations, the Supreme Court’s Civil Rights Cases of 1883 held that the law did not apply to private persons or corporations, the Court made clear that the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment provided no guarantee against private segregation.

In 1890 Louisiana legislature passed Louisiana’s Separate Car Act, the law, applicable to instate travel that required that all railroads operating in the state provide “equal but separate accommodations” for white and African American passengers. The Act made railroads provide two or more passenger coaches for each passenger train, or divide the passenger coaches by partition to secure separate accommodations and to prohibit passengers from entering accommodations other than those to which they have been assigned on the basis of their race. Violators of the Act could have been fined ($25) or imprisoned for up to 20 days.

Homer Plessy’s (the Petitioner in this case) arrest was no accident, but a pre-planned attempt to build a test case to challenge the Separate Car Act, organized by a group of Creole professionals in New Orleans known as the Committee of Citizens. Homer Plessy, a person of mixed race, was deliberately chosen as a Plaintiff in order to support the contention that the law could not be consistently applied because it failed to define white and “colored” races. Even the railroad cooperated with the Committee of Citizens because, to comply with the requirements of the Act, they had to incur unnecessary expenses purchasing additional railroad cars.

After his arrest, Homer Plessy challenged the Separate Car Act, arguing that the state law which required Louisiana Railroad to segregate trains, denied him his rights under the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments of the United States Constitution. Judge John H. Ferguson, presiding over the case, dismissed the unconstitutionality argument of the Plaintiff, ruling that Louisiana had the right to regulate railroad companies while they operated within state boundaries. The Supreme Court of Louisiana granted a petition by Plessy for a writ of prohibition and certiorari from the dismissal of the unconstitutionality argument by Judge Ferguson.

In the state Supreme Court, Justice Charles Fenner presiding over the case held that the decision of the lower court did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment. In support of his opinion Justice Fenner cited a number of precedents: the precedent from the Massachusetts Supreme Court was used to address the argument that segregation perpetuated race prejudice, the decision famously stated: “This prejudice, if it exists, is not created by law, and probably cannot be changed by law;” the precedent from Pennsylvania stated: “To assert separateness is not to declare inferiority. . . . It is simply to say that following the order of Divine Providence, human authority ought not to compel these widely separated races to intermix.”

The Case

After the State Supreme Court granted Plessy’s request for a writ of error, the U.S. Supreme Court granted certiorari, and oral arguments were heard on April 13, 1896. One month later, the Court rendered its final decision in this case.

Samuel F. Phillips, F.D. McKenney, Albion W. Tourgée, and James C. Walker submitted the briefs on Plessy’s behalf to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Tourgée and Phillips appeared in court on behalf of Homer Plessy (the Petitioner). They argued that the law in question violated Thirteenth Amendment, prohibiting slavery, and the Fourteenth Amendment, which guarantees the same rights to all citizens of the United States, and the equal protection of those rights against the deprivation of life, liberty, or property without due process of law. Attorneys claimed that the reputation of being a black man was “property”, which, implied the inferiority of African Americans as compared to whites.

The State of Louisiana (the Respondent) argued that it is the right of each state to make rules to protect public safety. Segregated facilities reflected the public will in Louisiana. Separate but equal facilities provided the protections required by the Fourteenth Amendment and satisfied the demands of white citizens as well. They also argued that because the Civil Rights Cases of 1883 made clear that segregation in private matters does not concern the government, a state legislature shouldn’t be prohibited from enacting public segregation statutes.

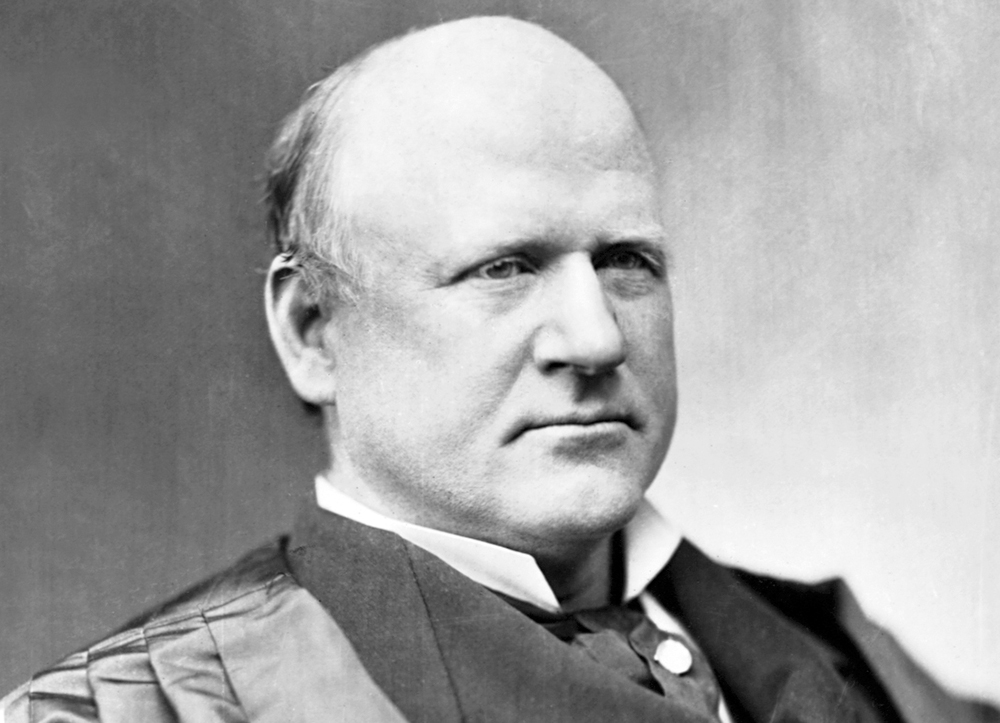

The seven-to-one majority opinion was authored by Justice Henry Billings Brown. Justice Brewer did not participate. The Court held that Louisiana’s law did not violate either the Thirteenth or Fourteenth Amendments. According to the Court, the Thirteenth Amendment applied only to slavery, and the Fourteenth Amendment was not intended to give African Americans social equality but only political and civil equality with white people. This line of reasoning will predominate political debate and court opinions for the next sixty years. In the majority decision, Justice Brown wrote that: “Legislation is powerless to eradicate racial instincts or to abolish distinctions based upon physical differences.”

In other words, legislation cannot change public attitudes, “and the attempt to do so can only result in accentuating the difficulties of the present situation.” Reflecting the common bias of the majority of the country at the time, Brown argued “if the civil and political rights of both races are equal, one cannot be inferior to the other civilly or politically. If one race is inferior to the other socially, the Constitution of the United States cannot put them upon the same plane”. The Court declared that Louisiana law was a reasonable exercise of the State’s “police power,” enacted for the promotion of the public good.

Ironically, while Justice Brown, a Northerner, justified the segregation, Justice John Marshall Harlan, a Southerner from Kentucky, made a lone, deep, and powerful dissent. The most famous line from Justice’s Harlan opinion states “Our Constitution is color-blind and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens.” Harlan’s dissent became the driving force behind the unanimous decision of the Court in Brown v. Board of Education in 1954. In his dissent Justice Harlan also wrote: “The present decision, it may well be apprehended, will not only stimulate aggressions, more or less brutal and irritating, upon the admitted rights of colored citizens but will encourage the belief that it is possible, by means of state enactment, to defeat the beneficent purpose which the people of the United States had in view when they adopted the recent amendments of the Constitution.”

Aftermath

Despite the predictions Justice Harlan made about the aggression that would follow from the decision, in this case, no great national protest followed. The decision was lightly reported and commented on and for a lot of people, segregation became a part of day-to-day life for the next 60 years until Brown v. Board of Education.

Overview

Brown v. Board of Education (also known as Brown I) is one of the greatest 20th-century decisions of the Supreme Court of the United States. By this decision, the Supreme Court unanimously declared that racial segregation of children in public schools violates the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. This groundbreaking and, for many, life-changing decision was rendered on May 17, 1954.

In 1954, a large portion of the United States had racially segregated schools, made legal by Plessy v. Ferguson, but the civil rights movement was setting up a stage to change that. In the early 1950s, NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) lawyers brought a class action on behalf of black school children and their families in Kansas, South Carolina, Virginia, and Delaware, seeking court orders to compel school districts to let black students attend white public schools.

One of these class actions, Brown v. Board of Education, was filed against the Topeka, Kansas school board by the representative of the plaintiff Oliver Brown, whose children were denied access to Topeka’s white schools. Brown claimed that Topeka’s racial segregation violated the Constitution’s Equal Protection Clause because the city’s black and white schools were not equal and never could be. The District Court dismissed his claim, ruling that the segregated public schools were “substantially” equal enough to be constitutional under the Plessy doctrine. Brown petitioned the Supreme Court of the United States, which consolidated all school segregation actions together for their review. Thurgood Marshall, who would in 1967 be appointed the first black justice of the Court, was chief counsel for the plaintiffs.

The unanimous (9-0) decision in Brown v. Board of Education, delivered by Justice Earl Warren, overturned Plessy v. Ferguson, once and for all banning states from allowing segregation in public education, stating that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.” As a result, segregation mandated by state and local laws was ruled to be a violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution of the United States.

One downfall of the decision in Brown I was that the decision itself did not provide any instruction, procedures, or safeguards for ending segregation. Trying to address this problem, the Supreme Court issued the decision in “Brown II” that came a year after Brown I, but it didn’t provide much guidance either, it only ordered states to desegregate “with all deliberate speed.”

Background

The implications of the Plessy v. Ferguson decision for education became apparent three years after the decision. In 1897, the Richmond County, Georgia school board closed the only African American high school in Georgia, even though state law required that school boards “provide of the same facilities for each race, including schoolhouses and all other matters appertaining to education.” At that time, the school board provided two high schools for white children. It also provided sufficient funds to educate all white children in the area, while it provided funding for only half of the school-aged African American children.

The Supreme Court upheld the county’s decision. In the case of Cumming v. School Board of Richmond County, GA, (1899), it ruled that African Americans not only had to show that a law or practice discriminated against them, but that it was adopted because of “racial hostility.” Even though the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) was trying to fight segregation since the early 1900s, by the 1950s segregation laws were deeply integrated into the United States educational system.

Just like Plessy v. Ferguson, Brown v. Board of Education did not get to the Supreme Court by accident; the whole case was built as a test case in the wake of significant political and social changes. The United States and the Soviet Union were both at the height of the Cold War during this time, and U.S. officials, including Supreme Court Justices, were highly aware of the harm that segregation and racism played on America’s international image. When Justice Douglas traveled to India in 1950, the first question he was asked was, “Why does America tolerate the lynching of Negroes?” Douglas later wrote that he had learned from all of his travels that “the attitude of the United States toward its colored minorities is a powerful factor in our relations with India.”

Chief Justice Warren, who authored the unanimous opinion of the Court in Brown I, echoed Douglas’s concerns in a 1954 speech to the American Bar Association, proclaiming that “Our American system like all others is on trial both at home and abroad, … the extent to which we maintain the spirit of our constitution with its Bill of Rights, will, in the long run, do more to make it both secure and the object of adulation than the number of hydrogen bombs we stockpile.”

In 1951, a class action was filed by thirteen Topeka parents (Oliver Brown, Darlene Brown, Lena Carper, Sadie Emmanuel, Marguerite Emerson, Shirley Fleming, Zelma Henderson, Shirley Hodison, Maude Lawton, Alma Lewis, Iona Richardson, and Lucinda Todd) on behalf of their 20 children against the Board of Education of the City of Topeka, Kansas in the United States District Court for the District of Kansas. The Topeka Board of Education operated separate elementary schools under an 1879 Kansas law, which allowed but didn’t require districts to maintain separate elementary schools for black and white students in 12 communities with over 15,000 population.

This lawsuit asked for the school district to reverse its policy of racial segregation. Oliver Brown, the named Plaintiff, was an African American, a welder, and the father of Linda Carol Brown, a third grader, who had to walk six blocks to her school bus stop to ride 1 mile to her segregated school (Monroe Elementary) while a white school was seven blocks from her house. Mr. Brown was assigned to be a named Plaintiff because the NAACP believed that his claim would be better received by the Supreme Court Justices.

Other parents got involved through the NAACP. They were directed to attempt to enroll their children in the closest neighborhood schools in the fall of 1951, and they were all refused the enrollment and directed to the segregated schools. Citing Plessy v. Ferguson, the District Court ruled in favor of the Board of Education. The three-judge panel found that segregation in public education has a detrimental effect on black children but denied relief on the ground that the black and white schools in Topeka were substantially equal with respect to buildings, transportation, curricula, and educational qualifications of teachers.

The Case

The U.S. Supreme Court case of Brown v. Board of Education combined five cases: Brown itself, Briggs v. Elliott (filed in South Carolina), Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County (filed in Virginia), Gebhart v. Belton (filed in Delaware), and Bolling v. Sharpe (filed in Washington, D.C.).

The Supreme Court first heard arguments for the case in December 1952 but because of the controversial nature of this case and anticipated resistance from southern states, no decision was reached. Justices asked to rehear the case in the fall of 1953, with special attention to whether the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause prohibited the operation of separate public schools for whites and blacks.

During the Court’s recess, Chief Justice Vinson died, and Chief Justice Warren was nominated by President Eisenhower and appointed to the Supreme Court. In December 1953, the Court heard the case again. Parties made the following arguments:

For the Petitioner: Led by Thurgood Marshall, an NAACP, Brown’s attorneys argued that the operation of separate schools, based on race, was harmful to African-American children. Extensive testimony supported the contention that legal segregation resulted in both fundamentally unequal education and low self-esteem among minority students. Lawyers argued that segregation by law implied that African Americans were inherently inferior to whites. For these reasons, they asked the Court to strike down segregation under the law.

For the Respondent: Attorneys for Topeka argued that the separate schools for nonwhites in Topeka were equal in every way and were in complete conformity with Plessy v. Ferguson. Buildings, the courses of study offered, and the quality of teachers were completely comparable, and because some federal funds for Native Americans only applied at nonwhite schools, some programs for minority children were actually better than those offered at the schools for whites. They pointed to the Plessy decision to support segregation and argued that they had in good faith created “equal facilities,” even though races were segregated. Furthermore, they argued, that discrimination by race did not harm children.

On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court of the United States unanimously ruled that segregation in public schools is unconstitutional. The Court said, “Separate is not equal,” and segregation violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Chief Justice Warren wrote in his first decision on the Supreme Court of the United States, “Segregation in public education is a denial of the equal protection of the laws. To separate some children from others of similar age and qualifications solely because of their race generates a feeling of inferiority as to their status in the community that may affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely ever to be undone.”

The change in the court’s perception of segregation and its decision in Brown I was influenced by UNESCO’s 1950 Statement, The Race Question, as well as an article by Gunnar Myrdal, An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy (1944), denouncing previous attempts at scientifically justifying racism. Another work that the Supreme Court cited was the research performed by the educational psychologists Kenneth B. Clark and Mamie Phipps Clark. The Clarks’ “doll test” studies presented substantial arguments to the Supreme Court about how segregation affected black schoolchildren’s mental status.

The Court also quoted the Kansas court, which had held that “Segregation of white and colored children in public schools has a detrimental effect upon the colored children. The impact is greater when it has the sanction of the law; for the policy of separating the races is usually interpreted as denoting the inferiority of the negro group. A sense of inferiority affects the motivation of a child to learn. Segregation with the sanction of law, therefore, has a tendency to retard the educational and mental development of negro children and to deprive them of some of the benefits they would receive in a racially integrated school.”

In the conclusion, Warren wrote: “We conclude that in the field of public education, the doctrine of ‘separate but equal has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal; segregation in public education is a denial of the equal protection of the laws.”

Brown v. Board of Education did more than reverse the “separate but equal” doctrine. It reversed centuries of segregation practice in the United States. This decision became the cornerstone of the social justice movement of the 1950s and 1960s. More than three-quarters of the century after the Fourteenth Amendment was passed, this decision brought life to the Amendment.

Aftermath

In Brown II (1955) the Court held that the problems identified in Brown I required varied local solutions. Chief Justice Warren conferred the responsibility of implementing desegregation on local school authorities and the courts which originally heard school segregation cases. They were ordered to implement the principles which the Supreme Court embraced in Brown I. Warren urged localities to act on the new principles promptly and to move toward full compliance with them “with all deliberate speed.”

In the years immediately following Brown, school districts responded in different ways. Some, like Prince Edward County, Virginia, simply shut their doors rather than accept integration. Other districts introduced a variety of programs meant to satisfy the Court. Some were evasive; others were constructed in good faith. But by the end of the 1960s, the Court had lost patience with the lack of progress toward integration, and in a series of decisions, it placed more precise and urgent demands on school districts.

The first of these decisions involved a “freedom of choice” program introduced in Virginia. Virginia’s Schools offered students the freedom to annually choose the school they would attend. On its face, the plan seemed like a sound approach to achieving educational equality. But in 1968, in Green v. School Board of New Kent County, the Supreme Court held that it was not. The Court stated that the freedom to choose could easily result in the perpetuation of traditional attendance patterns, the Court ruled that district integration plans must promise to achieve the actual objective of integration. School integration could not be left to chance, and districts must assume an “affirmative obligation” to bring about integrated schools.

The following year, in Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education, the Court created a timetable for integrating America’s schools by ruling that, with Brown now fifteen years in the past, “all deliberate speed” meant now.

In 1971, the Court came up with more precise instructions as to how school districts should meet their pressing legal obligations. In Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg, the Court announced that the discovery of a racially imbalanced school would trigger close scrutiny review by the courts, and the burden would lie with the district to prove that the racial imbalance was not the result of current or past practices. In addition, the Court told districts that to correct these conditions they should consider redrawing school boundaries and consider the transportation of students to schools in other parts of the district in order to bring about greater racial parity.

The combination was a clear message that the Court would no longer tolerate states dragging their feet when it comes to the desegregation of schools, and in subsequent years, the Court added that the North will be subject to the same scrutiny as the South when it comes to their discriminatory policies. In the North, however, school segregation was rarely the result of local or state law, nor was it the result of explicit district policy. More often it was due to officials’ practice, rather than official policy. In addition, racial imbalance was often a characteristic of only certain schools within a district. This all meant that it would be hard to prove a system-wide discriminatory practice warranting district-wide judicial intervention. But in Keyes v. Denver (1973), the Court held that evidence of discrimination in one part of the district justified a conclusion of district-wide discriminatory practice. The burden would lie with the district to prove otherwise.

In subsequent decisions, the Supreme Court decided to speed up the desegregation process even further. In Milliken v. Bradley, the Court held that, even though a district’s current practices might comply with the Court’s standards, the Court could force a district to set up remedial programs to close educational gaps resulting from past behaviors. In 1990, in Missouri v. Jenkins, the Court held that federal courts could even order local districts to increase taxes in order to fund these remedial programs.

Finally, in 1992, the Court suggested that it would remain invested in local policies until all effects of past discriminatory behavior were eliminated. In United States v. Fordice, the Court held that even though the University of Mississippi currently maintained “race-neutral policies,” effects of its former discriminatory practices remained. For example, entrance standards at the historically white institutions were higher than those of the historically black institutions, a policy that was “suspect because it originated as a means of preserving segregation.”

The Court also mentioned that the state maintained duplicate programs, also suspiciously close to the state’s former “separate-but-equal” system. Until these remnants of the state’s old segregated college system were eliminated, Mississippi had not met its obligations under the Fourteenth Amendment. As an outcome of these proactive decisions by the Supreme Court, many districts adopted affirmative action programs aimed at achieving racially balanced schools.

Although the decision did not succeed in fully desegregating public education in the United States, it propelled the civil rights movement.