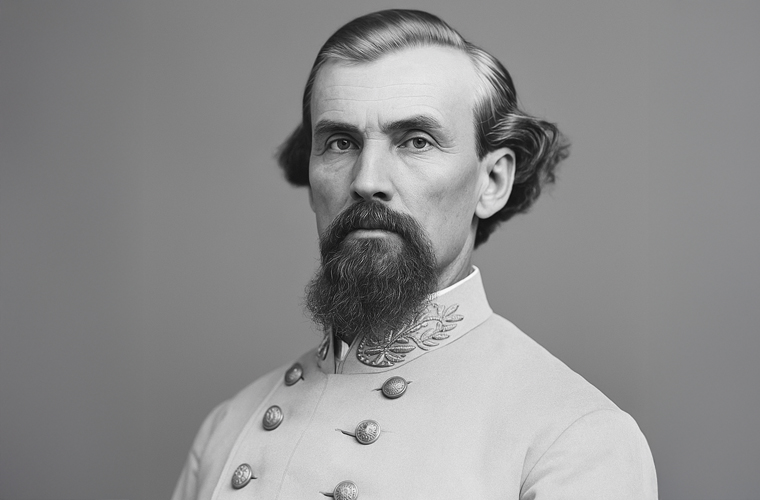

Nathan Bedford Forrest, born on July 13, 1821, near Chapel Hill, Tennessee, and dying on October 29, 1877, in Memphis, Tennessee, remains one of the most polarizing figures of the American Civil War and its aftermath. A Confederate cavalry commander, he earned a reputation as a formidable tactician, often described as a “born military genius” for his ability to outmaneuver opponents. His maxim, “Get there first with the most men,” encapsulated his aggressive approach to warfare and became one of the war’s most enduring quotes. Yet, his legacy is deeply controversial due to his role in the brutal Fort Pillow Massacre of 1864 and his leadership as the first grand wizard of the Ku Klux Klan during the early Reconstruction era.

Forrest’s early life was marked by hardship. Born into a poor family in rural Tennessee, he grew up in frontier conditions, moving to Mississippi as a young man. The premature death of his father thrust upon him the responsibility of supporting his family as a teenager. With little formal education, he developed a tough, self-reliant, and sometimes volatile disposition shaped by the demands of survival. Despite these challenges, he provided for his family, and after his mother’s remarriage, he pursued his ventures. In 1845, he married Mary Ann Montgomery, and together they had two children, only one of whom survived to adulthood. Through sheer determination, Forrest amassed a fortune through trading livestock, real estate, cotton planting, and, most lucratively, the slave trade. By the onset of the Civil War in 1861, he was among Tennessee’s wealthiest men, if not the entire South.

When the war broke out, Forrest enlisted as a private in the Confederate army but quickly rose through the ranks. At the request of Tennessee’s governor, he raised and equipped a cavalry unit, earning a commission as a lieutenant colonel. His natural aptitude for battlefield tactics soon became evident. In early 1862, he distinguished himself during the defense of Fort Donelson, Tennessee, where he led his men in a daring escape rather than surrender with the bulk of the Confederate garrison. Promoted to colonel, he fought bravely at the Battle of Shiloh in April 1862, sustaining the first of several wartime wounds during the Confederate retreat. His reputation grew as he led a cavalry command to a stunning victory at Murfreesboro, Tennessee, in July 1862, earning a promotion to brigadier general.

As a semi-independent cavalry commander, Forrest conducted devastating raids against Union supply lines, depots, and garrisons across the Western theater, disrupting critical operations like Ulysses S. Grant’s Vicksburg Campaign. Some historians credit Forrest’s actions with delaying Vicksburg’s fall by months. In May 1863, he outmaneuvered Union Colonel Abel D. Streight, preventing him from severing the Western and Atlantic Railroad, a lifeline for the Confederate Army of Tennessee. At the Battle of Chickamauga in September 1863, Forrest’s command anchored the Confederate right flank and pursued retreating Union forces. However, his volatile temper led to a heated dispute with General Braxton Bragg, the army’s commander, culminating in Forrest threatening Bragg’s life. Though Forrest offered his resignation, Confederate President Jefferson Davis, recognizing his value, promoted him to major general instead.

Tasked with raising a new cavalry division, Forrest resumed his raids with a relatively inexperienced force. On April 12, 1864, his command attacked Fort Pillow, a small Union outpost on the Mississippi River north of Memphis, garrisoned by African American troops, Southern Unionists, and Confederate deserters. When surrender negotiations failed, Forrest’s forces stormed the fort in a chaotic and brutal assault. Evidence suggests that many African American soldiers were killed after attempting to surrender, with estimates of 277 to 295 Union troops—mostly Black—slain in what became known as the Fort Pillow Massacre. A congressional investigation, though partly propagandistic, confirmed the slaughter, fueling Northern outrage and inspiring the rallying cry “Remember Fort Pillow!” among African American Union soldiers. Forrest’s precise role remains debated, with conflicting accounts about his orders and response to the violence.

Despite this controversy, Forrest achieved his most tactically brilliant victory at Brice’s Crossroads, Mississippi, on June 10, 1864, decisively defeating a larger Union force through superior maneuvering. This success bolstered his reputation, and he continued to lead effective raids across Mississippi, Tennessee, and Alabama. In late 1864, he rejoined the Confederate Army of Tennessee, now under General John Bell Hood, for the disastrous Franklin-Nashville Campaign. After the Confederate defeat at Nashville in December 1864, Forrest’s stubborn rearguard actions covered the army’s retreat, earning him a promotion to lieutenant general. However, by 1865, his command was weakened by dwindling manpower, poor equipment, and inferior horses. In his final major engagement, he was defeated by Union General James H. Wilson at the Battle of Selma, Alabama, on April 2, 1865. Forrest surrendered his command in May 1865.

After the war, Forrest struggled to regain his prewar wealth. The abolition of slavery eliminated a key source of his fortune, and his postwar ventures, including managing the Selma, Marion, and Memphis Railroad and a plantation using convict labor, were far less successful. In 1867, Forrest became the first grand wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, a secret organization that used violence and intimidation to enforce white supremacy during Reconstruction. While his exact influence within the KKK is debated, his prominence likely boosted its membership. In 1869, he ordered the group’s dissolution, though local chapters persisted. In 1871, he testified before a congressional committee, denying KKK membership in often contradictory statements. Later in life, Forrest’s temperament and racial views appeared to soften, possibly due to age, exhaustion, or his conversion to Christianity.

Forrest’s legacy is deeply divisive. His wartime exploits and rise from humble origins have made him a folk hero to some, particularly white Southerners, who view him as a symbol of Confederate valor alongside figures like Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson. However, his involvement in the Fort Pillow Massacre and the KKK has drawn widespread condemnation, especially from African Americans and civil rights advocates. In recent decades, efforts to commemorate Forrest—through schools, streets, parks, and statues—have sparked intense debate. In Memphis, Health Sciences Park (formerly Nathan Bedford Forrest Park), which houses his grave and a large equestrian statue, has been a flashpoint for both KKK rallies and civil rights protests. Renaming efforts and calls to remove Confederate monuments reflect ongoing struggles over his place in American memory, balancing his military prowess with his role in some of the Civil War era’s darkest chapters.