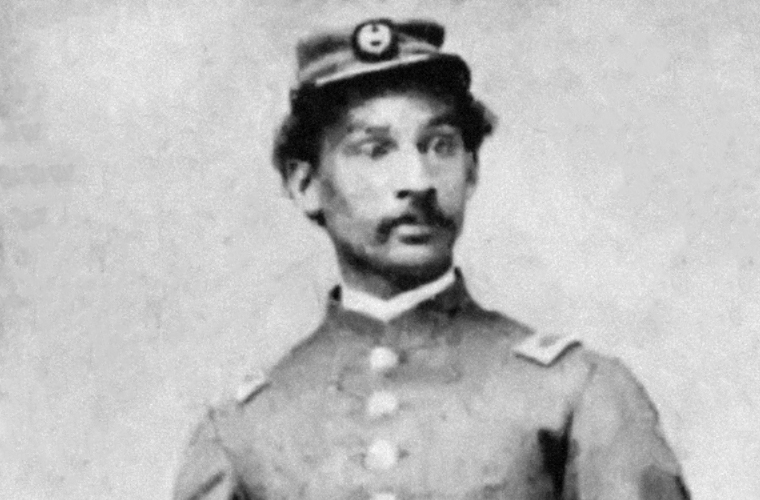

Anderson Ruffin Abbott, physician, educator, journalist, office holder, and hospital administrator; b. 7 April 1837 in Toronto, son of Wilson Ruffin Abbott and Ellen Toyer; m. 9 Aug. 1871 Mary Ann Casey in Toronto, and they had three daughters and two sons; d. there 29 Dec. 1913.

Anderson R. Abbott was born into a prominent black family in Toronto. After his parents’ store in Alabama had been ransacked, they moved to the northern states. They lived a short time in New York, but in 1835 or 1836 the negative racial climate precipitated their relocation in Toronto. Wilson Abbott soon began to acquire land and buildings – by 1871 he would own 48 properties, most of them in Toronto – and he became active in politics.

His family’s means and his keen intellect allowed Anderson to receive an excellent education. He attended private and public institutions, including William King*’s school in the black settlement of Buxton, near Chatham. From there he went to the Toronto Academy, where he was an honor student; after about three years he left to study at Oberlin College in Ohio. He returned to Toronto and, according to historian Daniel G. Hill, graduated from the Toronto School of Medicine in 1857. By Abbott’s own account, he matriculated in medicine that year at the University of Toronto, but, instead of continuing there, studied for four years under a black doctor, Alexander Thomas Augusta. Abbott became the first Canadian-born black doctor in 1861 when he received a license to practice from the Medical Board of Upper Canada.

In February 1863, during the American Civil War, he applied for a commission as an assistant surgeon in the Union army. His offer was evidently not accepted. In April Abbott, who was conscious of the risks faced by blacks in the military, reapplied, this time to be a “medical cadet” in a colored regiment. He was finally taken on as a civilian surgeon under contract. Between June 1863 and August 1865 he served in Washington, D.C., first at the Contraband Hospital (Camp Baker) and then at the Freedman’s Hospital; subsequently he had charge of a hospital in Arlington, across the Potomac from Washington. Abbott received numerous commendations and became popular in Washington society. Among the select group who stood vigil over the dying President Abraham Lincoln in April 1865, he was later presented by Mary Todd Lincoln with a shawl her husband had worn to his first inauguration.

Abbott resigned in April 1866 and returned to Canada later that year. He attended primary medical classes at the University of Toronto in 1867, and, although he would never graduate, he established a practice. In 1871 he was admitted to the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario. Following his marriage, in an Anglican ceremony to the 18-year-old daughter of a successful black barber, he and his wife moved to Chatham, where Abbott resumed practice.

Like his father, Abbott soon became an important member of his community. As president of the Wilberforce Educational Institute from 1873 to 1880, he fought against racially segregated schools in the area. In 1874 he was appointed a coroner for Kent County. A contributor to the Chatham Planet, he also found time to be associate editor of the Messenger, the journal of the local British Methodist Episcopal Church. In 1878 he was made the president of both the Chatham Literary and Debating Society and the Chatham Medical Society.

In 1881 Abbott moved his practice to Dundas, Ont., where he once again secured a number of positions, including high school trustee (1883) and chairman of the town’s internal management committee (1885–89). The family moved to Oakville in 1889 and back to Toronto the next year. In 1891 Abbott was elected a member of the James S. Knowlton Post No.532, Grand Army of the Republic, one of 273 Civil War veterans in Toronto to wear the GAR badge. He was known as Captain Abbott, a rank which some sources ascribe to his war years but which was likely an honorary rank later given him by the GAR. Additional recognition came in November 1892, when Abbott was appointed aide-de-camp “on the Staff of the Commanding Officers Dept.” of New York, the highest military honor ever bestowed to that time on a person of African descent in Canada or the United States, and a source of great pride for Abbott and his family.

In 1894 Abbott’s professional life took another turn when he accepted appointment as surgeon-in-chief at Provident Hospital in Chicago. Established in 1892, it was the first training hospital for black nurses in the United States. In 1896 he became Provident’s medical superintendent; he resigned the following year, citing “business reasons” as the cause.

Abbott returned to Toronto, where he resumed private practice and increasingly dedicated himself to writing editorials and articles for newspapers and magazines, among them the Colored American Magazine (Boston; New York), the Anglo-American Magazine (London), and the New York Age. His subjects included black history, the Civil War, Darwinism, biology, poetry, and medicine. At the turn of the century, he became embroiled in the debate between William Edward Burghardt Du Bois and Booker Taliaferro Washington over social change for blacks. Not surprisingly he sided with Du Bois in the belief that the access of blacks to higher education should not be compromised; his own life was a good example of what a gifted person of color could achieve when given a chance. He nevertheless believed that ultimately blacks would be assimilated: “It is just as natural for two races living together on the same soil to blend as it is for the waters of two river tributaries to mingle.” With Canada’s black population on the decline, he argued further that “by the process of absorption and expatriation the color line will eventually fade out in Canada.”

In 1913, at the age of 76, Anderson R. Abbott died in the home of his son-in-law Frederick Langdon Hubbard, son of his long-time friend, black municipal reformer William Peyton