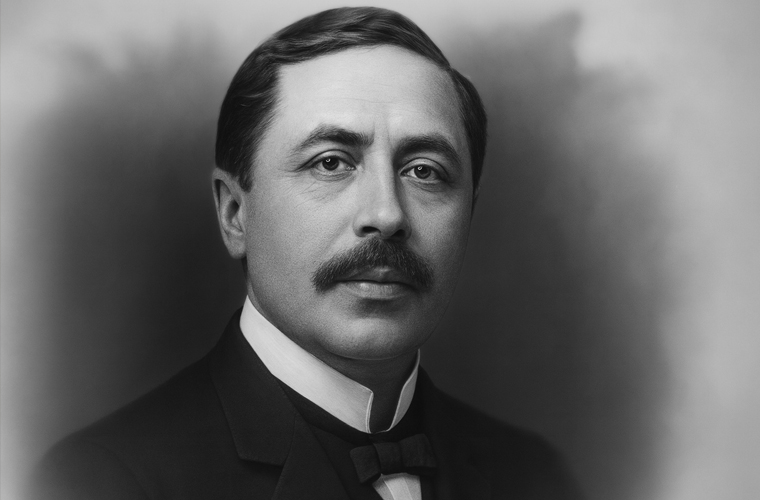

Pioneering Black Lawyer and Judge

Macon Bolling Allen, born Allen Macon Bolling in 1816 in Indiana, holds the distinction of being the first Black man licensed to practice law in the United States, a groundbreaking achievement in an era marked by pervasive racial discrimination. Born free in a state where slavery was prohibited, Allen’s early life was shaped by his determination to educate himself. With no formal schooling available to him, he taught himself to read and write, skills that would prove foundational to his later success. As a young man, he secured a position as a schoolteacher, where he not only imparted knowledge to his students but also refined his own intellectual abilities, developing a keen interest in law.

In the early 1840s, seeking greater opportunities, Allen left Indiana for Portland, Maine. It was there that he adopted the name Macon Bolling Allen, a decision that may have reflected a desire to redefine his identity as he pursued his ambitions. In Portland, he forged a significant relationship with General Samuel Fessenden, a prominent local lawyer and fervent anti-slavery advocate. Fessenden recognized Allen’s potential and took him on as an apprentice and law clerk, providing him with practical legal training at a time when formal law schools were rare and inaccessible to Black individuals.

Under Fessenden’s mentorship, Allen immersed himself in the study of law, gaining the knowledge and confidence necessary to practice. By 1844, Fessenden believed Allen was ready to join the legal profession and presented him to the Portland District Court, advocating for his admission to the bar. However, Allen’s application was initially rejected because he was not considered a citizen of Maine, a requirement for bar admission. Undeterred, Allen pursued an alternative path offered by Maine law, which allowed individuals of “good moral character” to be admitted through examination. He successfully passed the bar exam, earned a recommendation, and was granted citizenship, culminating in his licensing to practice law on July 3, 1844. This historic achievement made him the first Black lawyer in the United States, breaking a significant racial barrier in the legal profession.

Despite his licensure, practicing law in Maine proved difficult. The state’s small Black population limited Allen’s potential client base, and systemic racism meant that most white residents were unwilling to hire a Black lawyer to represent them in court. Facing these obstacles, Allen relocated to Boston, Massachusetts, in 1845, a city with a more established Black community and a vibrant abolitionist movement. In Boston, he met and married Hannah Allen, and together they raised five sons, most of whom followed in their father’s footsteps by pursuing careers in education.

In Boston, Allen continued to break new ground. On May 5, 1845, he passed the Massachusetts Bar Exam, further solidifying his legal credentials. Shortly thereafter, he partnered with Robert Morris, Jr., another pioneering Black lawyer, to open the first Black law office in the United States. This partnership was a significant milestone, providing a platform for Black legal professionals to serve their community and challenge racial prejudices in the legal system. Allen’s ambitions extended beyond private practice. In 1848, he passed a rigorous examination to become a Justice of the Peace for Middlesex County, Massachusetts, a position that likely made him the first Black man to hold a judicial role in the United States. This appointment underscored his legal acumen and marked another historic first in his trailblazing career.

Following the Civil War, Allen sought new opportunities in the South, where Reconstruction policies offered greater prospects for Black professionals. He moved to Charleston, South Carolina, and established a legal practice in a region undergoing significant social and political transformation. In 1873, Allen was appointed as a judge in Charleston’s Inferior Court, a testament to his growing reputation and legal expertise. The following year, in 1874, he achieved another milestone when he was elected probate judge for Charleston County, South Carolina. These judicial appointments were remarkable in an era when Black individuals were rarely entrusted with positions of authority, particularly in the South.

As Reconstruction ended and racial backlash intensified, Allen faced new challenges. The rollback of Reconstruction-era protections prompted him to relocate once more, this time to Washington, D.C. There, he worked as an attorney for the Land and Improvement Association, a role that allowed him to continue practicing law while contributing to community development efforts. Allen remained active in his legal career until he died in 1894 at the age of 78. He was survived by his wife, Hannah, and one son, Arthur Allen.

Macon Bolling Allen’s life was defined by his relentless pursuit of justice and equality in the face of systemic barriers. As the first Black lawyer and likely the first Black judge in the United States, he paved the way for future generations of Black legal professionals. His achievements—securing a law license, establishing a Black law office, and serving in judicial roles—were not only personal triumphs but also powerful challenges to the racial inequalities of his time. Allen’s legacy endures as a testament to the resilience and determination required to break new ground in the fight for civil rights and equal opportunity.