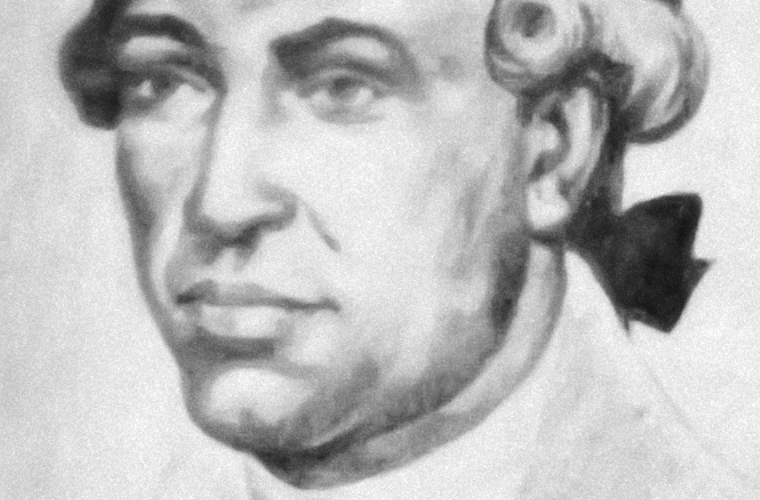

The founder of the first black lodge within the Masonic Order, Prince Hall (c.1735–1807) was a leading black citizen of Boston during the Revolutionary War era. A skilled orator, he pointed to the inherent hypocrisy of a war being waged in the name of freedom by a people that practiced the enslavement of others.

Hall supported the Revolution and may well have fought against the British. He emerged as a leader of Boston’s African-American community in the years after the war. Using his position as Worshipful Master or Grandmaster of Boston’s African Lodge No. 459 as a bully pulpit, he organized efforts to improve education for black Bostonians, to begin a back-to-Africa colonization movement, and to resist Northern participation in the slave trade. In the words of his Masonic biographer Charles H. Wesley, “His drive for freedom had a dual thrust. One directed against the dominating rule of a foreign power in the American colonies, and the other against the bondage of blacks.”

Records of the first third of Hall’s life are sparse. The slave trade in Massachusetts was heavy during the first half of the eighteenth century, and Hall’s speeches on behalf of African Americans sometimes referred to Africa as a native land, so he may have been born in Africa, but no records have surfaced to support either this idea or another early account stating that he was Barbadian by birth. The best guess as to Hall’s birthdate comes from records and newspaper accounts of his death in late 1807 that gave his age as 72, and thus probably places his birth in 1735. The first documentary evidence of his existence comes in the late 1740s in a list of slaves owned by William Hall of Boston, a leather-dresser or leather craftsman. It was probably from his master that Hall took his last name.

In 1756 Hall fathered a son, Primus, who likewise was involved with the Revolution and became an influential black Bostonian. The mother was a servant named Delia who worked in a nearby household. Hall joined a Congregational church in 1762 and married another slave, Sarah Ritchie (or Ritchery, the spelling on her gravestone), the following year. After her death, Hall was married four more times: to Flora Gibbs in 1770, Affee Moody in 1783, Nabby Ayrauly in 1798, and Zilpha (or Sylvia) Johnson in 1804. He learned the leather trade from his master and was given his freedom, in the form of a certificate of manumission, by William Hall in 1770. By Gibbs, he had another son, Prince Africanus.

Soon after marrying Gibbs, Hall acquired a small house with a workshop and opened a leather goods store called The Golden Fleece. He also worked as a caterer. Hall’s store later became a meeting place for the Masonic fraternity he organized. What drew Hall to Masonry in the first place is not known for certain, but fraternal organizations of various kinds served important community functions among free blacks at various stages in American history. Hall noticed that British soldiers in Boston had set up satellite chapters of Masonic lodges in their home countries, and he may have concluded that joining the Masons represented a path toward integration into the mainstream of American society. He may also have been motivated by the summary rejection of antislavery petitions by the colony’s government in 1773 and 1774. In 1775, just before the outbreak of war in Lexington and Concord, Hall was one of a group of 14 free blacks who became members of a Masonic lodge set up by British troops stationed in Boston, perhaps an offshoot of the Irish Lodge No. 441 in the city of Dublin. The date was said to be March 6, 1775.

The membership seemed to confer only partial rights within the Masonic organization, however. When the British garrison withdrew just days later, the sergeant who had headed the British group gave Hall and his companion permission to meet as a lodge and to march in public and funeral processions. But the group was not officially chartered and could not confer membership or degrees on other Masons. With Hall as master and leader, the black Masons formed the African Lodge No. 1 on July 3, 1775; it was the first black order of Free and Accepted Masons anywhere in the world.

The question of Hall’s actual participation in fighting against the British remains to be settled. Several histories of the large African-American presence in the American army (according to some estimates, one in every seven soldiers was black) state that he took up arms, but the name Prince Hall was a fairly common one. What can be documented is that Hall provided Revolutionary troops with leather drumheads, according to a 1777 bill of sale.

It was at around this time that Hall began to lead his fellow black Bostonians in trying to persuade the young nation to live up to its ideas of liberty and equality for all. He was one of four signers at the head of a 1777 petition demanding the abolition of slavery in Massachusetts. The petition’s aim, in its own words (as quoted by Sidney Kaplan in The Black Presence in the Era of the American Revolution), was that the “inhabitant of these Stats” would, if slavery were abolished, no longer be “chargeable with the inconsistency of acting themselves the part which they condemn and oppose in others.” The Massachusetts legislature sent a bill introduced by sympathetic white lawmakers along to the National Congress of the Confederation, but the petition was not acted upon; slavery in Massachusetts would not be abolished until 1783 when it was ended by a state judicial decision.

Hall continued to operate his successful leather shop and seek official recognition for his small Masonic lodge, its numbers further decimated as blacks joined the American army and were dispersed along the battlefront. In 1782 he penned a retort to a newspaper article that disparagingly referred to the lodge as “St. Blacks” and made light of its Feast of St. John observances. In 1784 Hall (as quoted by Kaplan) wrote to Masons in England that “this Lodge hath been founded almost eight years and we have had only a Permit to Walk on St. John’s Day and to Bury our Dead in manner and form … we hope [you] will not deny us nor treat us Beneath the rest of our fellowmen, although Poor yet Sincere Brethren of the Craft.” The lodge’s official charter was granted, but three years passed before it was issued and brought to America. What had been known as African Lodge No. 1 was now African Lodge No. 459.

Hall by that time was a Boston property owner, taxpayer, and voter, and the change solidified his status as a community leader. As a revolt among dispossessed farmers and war veterans broke out in western Massachusetts under the name Shays’s Rebellion, Hall and other blacks faced the problem of which side to support—and of whether their support would be welcomed. Hall wrote in November of 1786 to Massachusetts governor James Bowdoin offering to raise black volunteers for the effort to put down the rebellion. The offer was turned down by a state government afraid of what an armed black militia might do.

Disillusioned by this turn of events, Hall threw his support behind a still-tiny back-to-Africa movement. In time, the idea of African colonization would gain support and result in the establishment of the nation of Liberia, but Hall brought together 12 members of his lodge to sign a petition dated January 4, 1787, that was presented to the Massachusetts House, years ahead of even the earliest actual return voyages to Africa by African Americans or African Canadians. The importance of Hall’s petition lies less in its effect—it went nowhere—than in what it reveals about the deferral of African-American dreams that followed the American Revolution. Hall’s petition (quoted and reproduced by Kaplan) referred to “very disagreeable and disadvantageous circumstances; most of which must attend us, so long as we and our children live in America.”

With the failure of this initiative, Hall turned his attention to improving the living conditions of black Bostonians. In 1787 and again in 1796, he led drives to provide free state schooling for black Massachusetts children, which, he argued, they were entitled to inasmuch as black tax payments supported white schools. Finally, in 1800 he offered his own home for use as a school; two students from Harvard University agreed to serve as instructors.

Hall began to discuss the evils of slavery in general, and he developed into a powerful orator. In a 1797 Feast of St. John address to the African Lodge in West Cambridge (quoted by Kaplan), he spoke of the abuse black Bostonians endured on holidays at the hands of “a mob or horde of shameless, low-lived, envious, spiteful persons” who in groups of “twenty or thirty cowards fall upon one man” or tear the clothes of old women. But he looked to the slave revolt that had occurred in Haiti as a sign of hope: if liberty had begun “to dawn in some of the West-Indian islands, then, sure enough, God would act for justice in New England too, and let Boston and the World know, that He hath no respect of persons; and that that bulwark of envy, pride, scorn, and contempt, which is so visible to be seen in some … shall fall, to rise no more.”

The idea of black Masonry began to spread, especially as Hall’s lodge received chilly treatment from white Masonic groups. New lodges, often bearing Hall’s name, were chartered in other cities, beginning in 1797 in Providence, Rhode Island. A black Masonic lodge in Philadelphia played a key role in the evolution of independent black institutions in that city. Hall remained active until his death in Boston on April 4, 1807; his final interment the following year was attended by a large crowd of African Americans. The branch of Freemasonry he founded continued to exert a strong influence in black communities. The list of famous Prince Hall Masons in the twentieth century was a long one, and included educator Booker T. Washington, writer W.E.B. DuBois, Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, author Alex Haley, bandleaders William “Count” Basie, Lionel Hampton, and Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington, boxer Sugar Ray Robinson, publisher John H. Johnson, and Los Angeles mayor Tom Bradley, among many others.