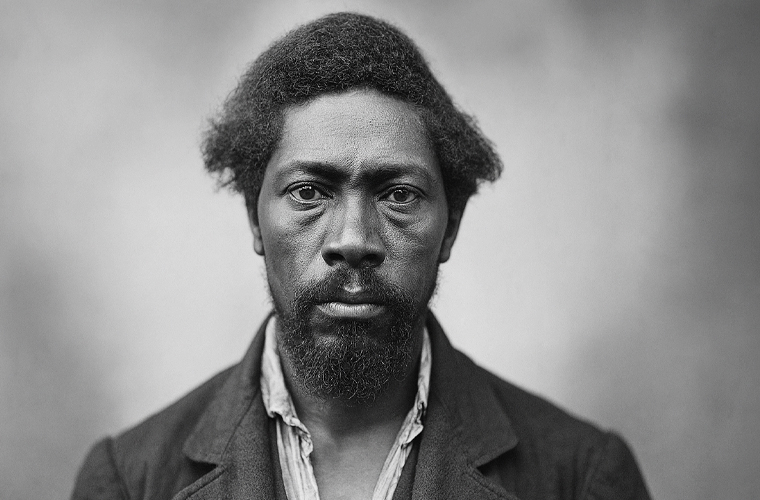

Dangerfield Newby (1815-1859) was an African American man whose life and actions left a lasting mark on the abolitionist movement and the turbulent events leading to the American Civil War. Born into slavery in Fauquier County, Virginia, Newby was owned by a man named John Newby, a white slaveholder who was also his father. This complex familial tie did not shield him from the harsh realities of enslavement. In the 1850s, Newby married Harriet, a woman enslaved on a nearby plantation owned by a different slaveholder, Lewis Jennings. Together, they had several children, all of whom were also enslaved, their lives controlled by Jennings. The separation of his family weighed heavily on Newby, and he became consumed with securing their freedom, a pursuit that defined his later actions.

In his early years, Newby experienced a degree of mobility uncommon for most enslaved people. His father, upon manumitting him around 1858, allowed him to live as a free man in Ohio, where he worked as a blacksmith and saved money to buy his family’s freedom. However, the cost of freeing Harriet and their children—estimated at over $1,000, an immense sum for the time—proved daunting. Harriet’s owner was willing to sell, but Newby’s earnings were insufficient, and his repeated attempts to negotiate their release met with frustration. Letters from Harriet, found on Newby’s body after his death, revealed her growing fear of being sold further south, away from him and their children, intensifying his urgency.

This desperation led Newby to John Brown, a radical abolitionist whose fiery commitment to ending slavery resonated with Newby’s mission. Brown was organizing a bold plan: to seize the federal armory at Harpers Ferry in present-day West Virginia, arm enslaved people with the captured weapons, and ignite a widespread slave rebellion that would dismantle the institution of slavery. Newby, seeing the raid as a potential means to secure the funds or leverage needed to free his family, joined Brown’s small band of 21 men, which included both Black and white abolitionists. As one of the few Black participants, Newby’s involvement was driven by a deeply personal stake in the fight for freedom.

The raid, launched on October 16, 1859, quickly unraveled. Brown’s group captured the armory but failed to rally significant local support from enslaved people, who were either unaware of the plan or wary of its risks. Local militia and townspeople surrounded the raiders, cutting off their escape. By October 18, U.S. Marines under Colonel Robert E. Lee stormed the armory, overpowering Brown’s men. Newby was one of the first to fall, shot in the neck by a sniper while guarding a position near the armory. His death was brutal; after he was killed, townspeople reportedly mutilated his body, a grim testament to the era’s racial violence. The letters from Harriet found on him underscored the personal stakes of his sacrifice, amplifying the tragedy of his loss.

Newby’s death marked a poignant chapter in the broader struggle against slavery. The Harpers Ferry raid, though a tactical failure, sent shockwaves through the nation. In the South, it fueled paranoia about slave insurrections, prompting harsher laws and increased militancy in defense of slavery. In the North, it galvanized abolitionists, with figures like Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman praising Brown’s audacity, even if they questioned his strategy. Newby’s role, though less documented than Brown’s, embodied the courage and desperation of enslaved individuals who risked everything for freedom. His story also highlighted the fractured nature of enslaved families, torn apart by a system that treated them as property, and the extraordinary lengths to which they went to reunite and reclaim their humanity.

The aftermath of the raid saw Newby’s family remain in bondage, their fate uncertain in the immediate years following his death. However, the raid’s failure did not diminish its long-term impact. It heightened sectional tensions, pushing the nation closer to the Civil War, which began less than two years later. The war ultimately led to the Emancipation Proclamation and the Thirteenth Amendment, abolishing slavery. Newby’s sacrifice, while deeply personal, contributed to this larger narrative of resistance and liberation, cementing his place as a figure of resilience in the fight for justice.