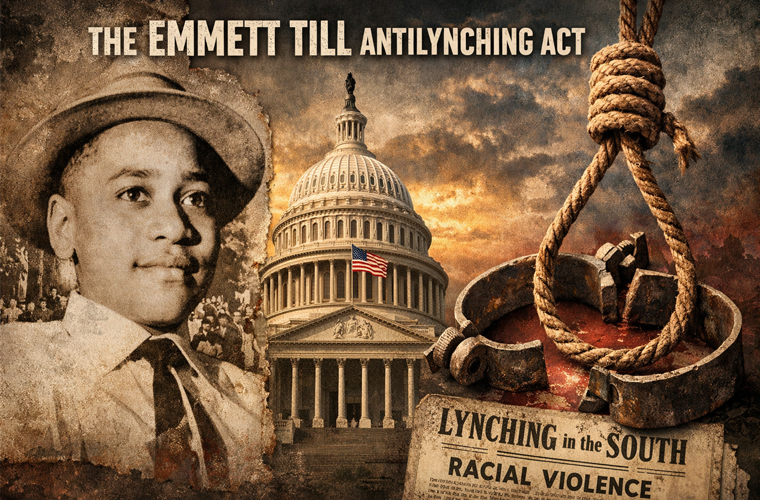

Justice Delayed, But Not Denied

In a landmark moment for American civil rights, President Joe Biden signed the Emmett Till Antilynching Act into law on March 29, 2022, making lynching a federal hate crime for the first time in U.S. history. This legislation, over a century in the making, amends federal hate crime statutes to impose severe penalties on those who conspire to commit racially motivated violence resulting in death or serious injury. Named after the 14-year-old Black boy whose brutal 1955 murder galvanized the Civil Rights Movement, the act represents a hard-won victory against one of the darkest chapters in American history: the era of unchecked racial terror through lynching.

The Tragic Story of Emmett Till

Emmett Till’s name evokes profound sorrow and outrage. In August 1955, the Chicago-born teenager was visiting relatives in Money, Mississippi, when he was accused of whistling at or making advances toward Carolyn Bryant, a white woman. Days later, her husband Roy Bryant and his half-brother J.W. Milam abducted Till from his uncle’s home, brutally beat him, shot him in the head, and dumped his mutilated body in the Tallahatchie River. Till’s mother, Mamie Till-Mobley, insisted on an open-casket funeral, allowing the world to witness the horrors inflicted on her son. The images sparked national and international fury.

Despite overwhelming evidence, an all-white jury acquitted Bryant and Milam after a sham trial lasting just hours. Protected by double jeopardy, the men later confessed to the murder in a magazine interview, admitting they had acted out of racial hatred. Till’s death became a catalyst for the Montgomery Bus Boycott and broader civil rights activism, but federal inaction on lynching persisted for decades.

A Long Fight Against Lynching

Lynching—extrajudicial mob violence, often targeting Black Americans—claimed thousands of lives between the late 19th and mid-20th centuries, with at least 4,743 documented cases from 1882 to 1968, according to the Equal Justice Initiative. Congress first attempted to criminalize it with the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill in 1918, sponsored by Missouri Rep. Leonidas Dyer, which proposed fines up to $10,000 and imprisonment for perpetrators. Southern Democrats filibustered it, labeling it an overreach into states’ rights.

Over 200 anti-lynching bills followed, including the Costigan-Wagner Bill in the 1930s and the Justice for Victims of Lynching Act in 2018, all failing amid political opposition. President Franklin D. Roosevelt refused to support earlier versions, fearing backlash from Southern allies. It wasn’t until the Civil Rights Act of 1968 that federal hate crime laws emerged, but they didn’t explicitly address lynching. The Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act of 2009 expanded protections but left this gap.

The Emmett Till Act finally closed it, building on these foundations by amending 18 U.S.C. § 249, which prohibits willfully injuring, intimidating, or interfering with federally protected activities based on bias.

Provisions of the Act

The Emmett Till Antilynching Act is concise yet powerful. It defines lynching as a conspiracy to commit a hate crime under existing federal statutes that results in death or serious bodily injury. Key elements include:

- Criminal Penalties: Offenders face fines, up to 30 years in prison, or both. This applies to conspirators, not just direct perpetrators—if a group plans a bias-motivated attack and it leads to harm, all involved can be prosecuted federally.

- Scope: Covers offenses like kidnapping, aggravated sexual abuse, attempted murder, or participation in a riot resulting in death, when motivated by race, color, religion, or national origin. It doesn’t create a new crime but enhances penalties for conspiracies.

- Limitations: Mere planning without action isn’t punishable, and bystanders unaffiliated with the conspiracy are exempt. The law aligns with the “serious bodily injury” standard to avoid overreach, as debated during its passage.

This framework ensures accountability for mob violence while respecting due process.

The Path to Passage

The act’s journey began in the 116th Congress with H.R. 35, introduced by Rep. Bobby Rush (D-IL) in 2019. The House passed it overwhelmingly in 2020, but Sen. Rand Paul (R-KY) blocked it in the Senate, objecting to its broad language. Amid the 2020 racial justice protests following George Floyd’s murder, pressure mounted.

Reintroduced as H.R. 55 in 2021, the bill incorporated Paul’s suggested amendments for stricter injury thresholds. The House approved it 422–3 in February 2022. In the Senate, Sen. Cory Booker (D-NJ) led S. 3710, which passed unanimously on March 7. Biden’s signing ceremony, attended by Till’s family, civil rights leaders like Rev. Al Sharpton, and descendants of lynching victims, underscored its emotional weight. As Biden remarked, “Lynching is pure terror to enforce the lie that not everyone… belongs in America.”

Impact and Legacy

Since its enactment, the act has symbolized a moral reckoning. The Department of Justice launched the Emmett Till Cold Case Investigations Program in 2020 (predating the law but aligned with it), funding probes into unsolved racial violence cases. In 2022, discussions arose about applying it to the Buffalo supermarket shooting, where a white supremacist killed 10 Black people, though it was prosecuted under other hate crime statutes.

As of 2026, no high-profile federal lynching prosecutions have been widely reported, but the law has bolstered civil rights enforcement. It complements state laws—47 states plus D.C. have bias crime statutes—and addresses historical impunity. Critics argue it doesn’t go far enough without a standalone lynching definition, but advocates hail it as a deterrent against modern equivalents like hate-fueled mob attacks.

The act’s passage also amplified calls for truth and reconciliation. In 2025, newly released Emmett Till lynching records revealed government responses—or lack thereof—shedding light on systemic failures.

The Emmett Till Antilynching Act is more than legislation; it’s a testament to persistence against injustice. From the river where Till’s body was found to the Rose Garden where the bill became law, it bridges a painful past with a commitment to equity. As Mamie Till-Mobley once said, “Two months ago I had a nice dream. I picked up the morning paper, and it read, ‘Tallahatchie River Drained of Mud,’ and you know, the mud was the prejudice of the white people of the South.” While the river runs clear, the act ensures that prejudice’s violent fruits face federal reckoning. In honoring Till, America vows: Never again.