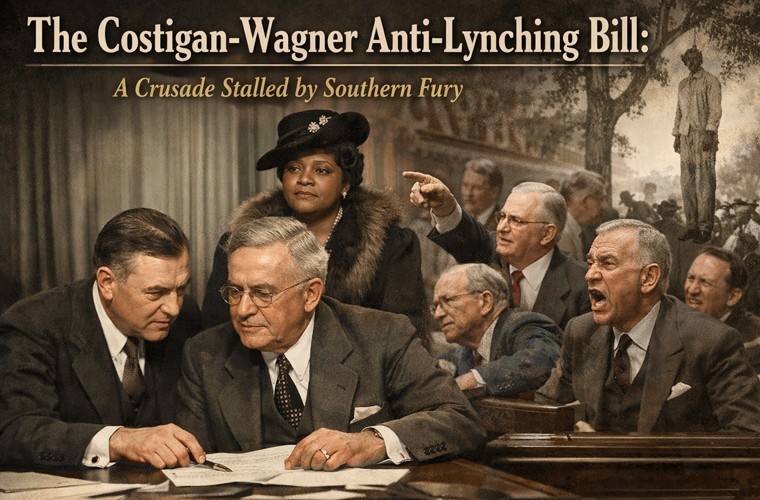

A Crusade Stalled by Southern Fury

In the shadow of the Great Depression, as America grappled with economic ruin, a darker crisis festered in the heartland: the scourge of lynching. Between 1882 and 1968, at least 4,743 individuals were lynched in the United States—3,446 of them Black—often with impunity under the Jim Crow regime of the South. These mob-driven executions, justified by flimsy accusations of crimes like “insulting whites” or economic competition, were not mere outliers but a systematic tool of racial terror. The Costigan-Wagner Anti-Lynching Bill of 1934 represented a pivotal federal challenge to this barbarity, proposing to make lynching a civil rights violation punishable by law. Sponsored by Senators Edward P. Costigan (D-CO) and Robert F. Wagner (D-NY), it galvanized civil rights advocates but ultimately crumbled under a Senate filibuster, exposing the raw political calculus of race in FDR’s New Deal era.

The Lynching Epidemic: A National Disgrace

Lynchings surged in the early 20th century, peaking in the 1890s but persisting into the 1930s with an average of 20-30 incidents annually. In 1933 alone, 28 lynchings were recorded, many in the South, where local sheriffs turned a blind eye or actively participated. High-profile cases, like the 1930 lynching of two Black youths in Indiana or the 1935 murder of Rubin Stacy in Florida—a starving father of five hanged for “scaring” a white woman—shocked the nation and fueled demands for action.

The NAACP, founded in 1909 partly in response to such violence, had long campaigned against it. Their 1919 report, Thirty Years of Lynching in the United States, documented the horror, but state-level inaction necessitated federal intervention. Earlier efforts, like the 1922 Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill (sponsored by Missouri Republican Leonidas Dyer), passed the House but died in the Senate amid Southern opposition. By 1932, as Franklin D. Roosevelt ascended to the presidency on a wave of hope, Black voters—courted by the NAACP’s Walter White and educator Mary McLeod Bethune—shifted en masse to the Democrats, expecting reciprocity. Eleanor Roosevelt, a fierce anti-lynching voice, amplified these calls, but FDR’s administration prioritized economic recovery over racial justice.

Drafting the Bill: Provisions for Federal Accountability

Introduced on January 15, 1934, as S. 197, the Costigan-Wagner Bill was a comprehensive assault on lynching’s enablers. Costigan, a progressive reformer from Colorado with a record of labor and civil rights advocacy, and Wagner, a New York stalwart behind the National Labor Relations Act, crafted it to bypass Southern courts by invoking the 14th Amendment’s equal protection clause.

Key provisions included:

- Federal Prosecution of Mobs: Lynchings would be treated as federal crimes, with participants facing up to five years in prison and fines up to $5,000. The bill targeted not just killers but conspirators, including those who incited or aided the violence.

- Liability for Officials: Sheriffs, deputies, or governors who failed to protect victims in custody—or who conspired with mobs—would face federal trials, mirroring civil rights enforcement mechanisms.

- County Compensation: Families of victims could sue counties for damages ($2,000 to $10,000), with federal courts overseeing cases if state bias was evident. This aimed to impose financial deterrents on complicit communities.

- Jurisdictional Override: If states refused to prosecute or impaneled prejudiced juries, the federal government could intervene, ensuring impartial justice.

The bill’s scope was revolutionary, shifting responsibility from negligent local authorities to Washington and framing lynching as a denial of citizenship rights rather than a “local matter.”

A Groundswell of Support: The NAACP’s Mobilization

The measure ignited a firestorm of advocacy. The NAACP, under executive secretary Walter White (a light-skinned investigator who infiltrated the KKK), launched a relentless campaign. White’s 1929 book Rope and Faggot: A Biography of Judge Lynch had already marshaled statistics to indict the practice, and he now flooded Congress with petitions. By 1935, over 2 million signatures backed the bill, including those from labor unions, religious groups, and women’s organizations.

Eleanor Roosevelt played a starring role, hosting White at the White House and publicly decrying lynching as “murder.” Mary McLeod Bethune, head of the National Council of Negro Women and FDR’s “Black Cabinet” advisor, rallied Black communities. Progressive senators like Robert La Follette Jr. (R-WI) and Democrats Hugo Black (AL, before his Supreme Court days) co-sponsored it. Handbills urged citizens: “Write to the President! Demand the Costigan-Wagner Bill!” Even Huey Long, the flamboyant Louisiana populist, faced NAACP scrutiny in a 1935 interview, where he dodged questions on a recent lynching.

This coalition reflected the New Deal’s fragile unity: Northern liberals and urban Black voters pushed for equity, while the bill’s passage could solidify FDR’s 1936 reelection.

Southern Backlash: Filibuster and FDR’s Reluctance

Opposition coalesced swiftly from the “Solid South,” where Democrats like Georgia’s Walter George and Mississippi’s Theodore Bilbo viewed the bill as an assault on states’ rights and white supremacy. They argued it federalized “local crimes” and risked Northern meddling in Southern “customs.” In December 1934, Southern senators threatened to filibuster any New Deal legislation if the bill advanced, weaponizing FDR’s slim majorities.

President Roosevelt, ever the pragmatist, withheld endorsement. In a 1935 meeting with White, he confided: “If I come out for the anti-lynching bill now, they will block every bill I ask Congress to pass.” Prioritizing Social Security and relief programs, FDR feared alienating the Southern bloc essential to his coalition. The Rubin Stacy lynching—photographed with his terrified daughter clinging to his legs—drew national outrage, but even Life magazine’s coverage failed to budge him.

Introduced in the Senate on January 3, 1935, as S. 24, the bill cleared the Judiciary Committee in March but stalled on the floor. A six-week filibuster by Southerners, invoking “sectional prejudice,” killed it in July 1935. The House passed a companion bill, but without Senate concurrence, it died.

Legacy: Seeds of Future Justice

The Costigan-Wagner Bill’s defeat was a bitter pill, but its echoes reverberated. It spotlighted lynching’s brutality, boosting NAACP membership and public discourse—The Crisis magazine’s coverage alone educated thousands. The 1937 Gavagan-Wagner Bill (H.R. 1502) revived the fight, passing the House twice but succumbing to another filibuster.

Decades later, these failures underscored the long arc of civil rights. The 1946 Gavagan Bill and 1950s efforts faltered similarly, until the 2022 Emmett Till Antilynching Act finally made lynching a federal hate crime—over 120 years after the first bill. As White reflected, the Costigan-Wagner crusade “broke the silence,” proving that federal power could confront racial terror, even if political will lagged. In an era when democracy itself hung by a thread, the bill stands as a testament to moral courage amid compromise—a reminder that progress, though delayed, is inexorable.