The Delaware Precursor to School Desegregation

In the annals of American civil rights history, few cases loom as large as Brown v. Board of Education (1954), the U.S. Supreme Court decision that declared racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional. Yet behind that landmark ruling lay a constellation of legal challenges from across the nation, including one from the unlikely border state of Delaware: Belton v. Gebhart. Often overshadowed by its more famous counterpart, this case—formally consolidated with Bulah v. Gebhart—not only exposed the stark inequalities of “separate but equal” education but also delivered a rare state-level victory for integration, influencing the Supreme Court’s ultimate rejection of segregation.

Delaware’s story with school segregation was a microcosm of the nation’s fractured racial landscape. Though it fought for the Union during the Civil War and was classified as a Northern state by some measures, Delaware clung to Jim Crow laws that mandated separate schools for Black and white children. The state constitution’s Article X, Section 2, paradoxically proclaimed “no distinction shall be made on account of race or color” while requiring segregated facilities. A 1935 education law reinforced this duality, promising “free” education to both races but delivering vastly inferior resources to Black students. Black schools suffered from dilapidated buildings, overcrowded classrooms, underqualified teachers, and limited curricula—conditions exacerbated by chronic underfunding.

By the early 1950s, the NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund, led by strategists like Thurgood Marshall and Robert L. Carter, targeted these disparities through a coordinated assault on Plessy v. Ferguson’s “separate but equal” doctrine. In Delaware, local attorney Louis L. Redding—the state’s first Black lawyer—teamed with Jack Greenberg to file two petitions in 1951, challenging the system in the Court of Chancery, Delaware’s equity court designed for remedies beyond mere monetary damages.

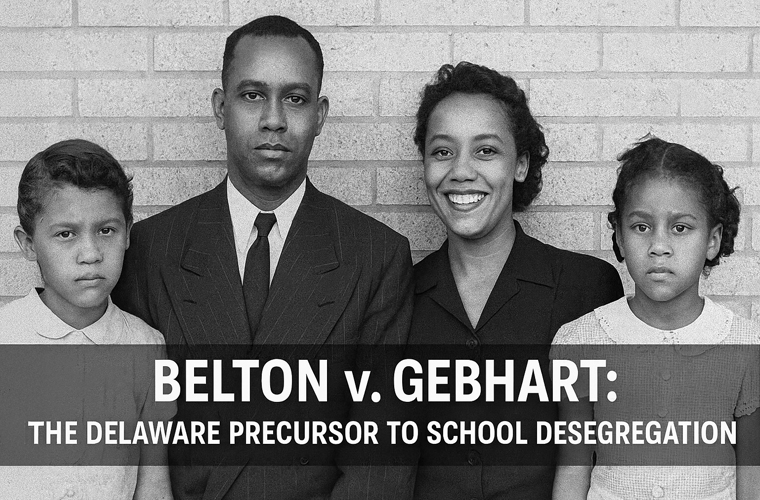

The cases centered on two groups of Black families denied access to superior white schools.

- Belton v. Gebhart: Ethel Belton and six other parents represented eight high school students from Claymont, a Wilmington suburb. Their children were bused 12 miles daily to Howard High School, Delaware’s sole Black high school, which boasted some DuPont-funded improvements but lagged in key areas: larger classes (up to 40 students versus 25 at Claymont High), fewer certified teachers, and a truncated curriculum lacking advanced courses like business or college prep. Vocational training required after-hours treks to a separate annex, underscoring the system’s inefficiencies.

- Bulah v. Gebhart: Sarah Bulah spoke for her adopted daughter, Shirley, a six-year-old in Hockessin. Shirley was barred from the modern Hockessin School No. 29—complete with indoor plumbing, a library, and bus service—and instead walked two miles to the one-room Hockessin School No. 107, a “colored” relic valued at $6,250 in fire insurance (versus $42,500 for No. 29). No bus for Black children meant daily treks past the white school’s transport, a humiliating symbol of inequality.

The plaintiffs’ core argument: Segregation violated the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause, either inherently or because Delaware’s “separate” schools were demonstrably unequal. Expert witnesses—psychologists, sociologists, and educators—testified unrebutted that such disparities inflicted psychological harm, stunting Black children’s development and perpetuating racial hierarchies.

Defendants, including State Board of Education President H. Albert Gebhart defended the status quo, claiming facilities were equal or that Plessy permitted separation regardless.

Presiding over the trial was Chancellor Collins J. Seitz, fresh from desegregating the University of Delaware in Parker v. University of Delaware (1950). Seitz candidly critiqued Plessy, calling for its overturn by higher courts, but, bound by precedent, he focused on inequality. In a sweeping 1952 opinion, he declared Howard and No. 107 “substantially inferior” in facilities, teacher quality, transportation, and curriculum—violating even the lax “separate but equal” standard.

Invoking Chancery’s equitable powers, Seitz ordered immediate admission of Black students to white schools: “The plaintiffs are hereby admitted to the white schools… under their control.” This was unprecedented among the Brown companion cases, where most lower courts upheld segregation.

The Delaware Supreme Court unanimously affirmed on August 28, 1952, upholding integration but sidestepping Plessy’s constitutionality, leaving room for future equalization efforts. Integration began fitfully: Claymont High enrolled 11 Black students days later amid local support, but statewide resistance delayed broader change until the Supreme Court weighed in.

Belton/Bulah v. Gebhart joined four other cases—Brown v. Board (Kansas), Briggs v. Elliott (South Carolina), Davis v. County School Board (Virginia), and Bolling v. Sharpe (D.C.)—forming the Brown docket. Unlike its peers, where federal judges deferred to Plessy, Delaware’s ruling provided a blueprint for inequality’s harms.

In 1954, Chief Justice Earl Warren’s unanimous opinion rejected segregation outright: “Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.” The Court affirmed Delaware’s integration order while remanding for remedy implementation, crediting social science evidence from Gebhart, like the “doll tests” showing segregation’s psychological toll.

Brown ignited desegregation nationwide, but Delaware’s path was rocky. Northern districts integrated swiftly, but Southern counties resisted, fueled by white supremacist Bryant Bowles’ NAAWP boycotts and protests, including the 1954 Milford High School standoff with cross burnings and National Guard intervention. Full compliance lagged until the 1960s, with some schools resegregating de facto through housing patterns.

Yet Belton v. Gebhart’s impact endures. It honored pioneers like Redding, commemorated by statues and schools, and underscored equity’s ongoing fight—echoed today in efforts like the Redding Consortium addressing resource gaps. As the only Brown case to mandate integration pre-Supreme Court, it remains a testament to grassroots courage and judicial foresight, reminding us that landmark change often begins in local courtrooms.