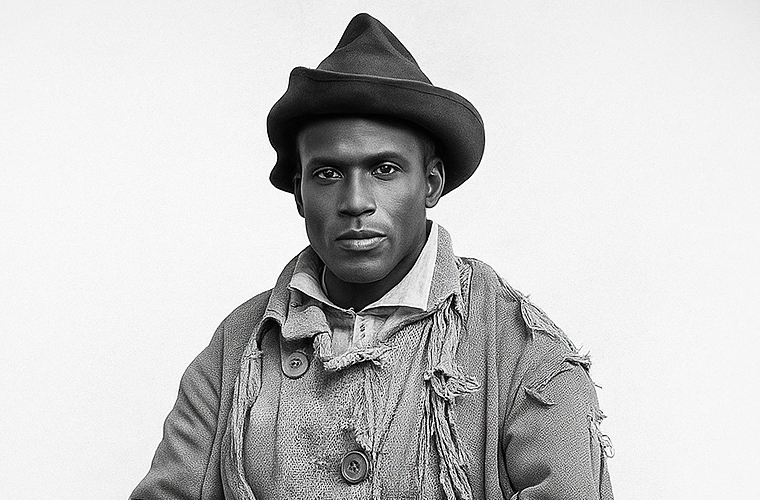

Gordon, widely known as “Whipped Peter,” was an African American who escaped slavery and became an enduring symbol of the abolitionist movement during the American Civil War. His fame stems from a series of haunting photographs that revealed the severe keloid scarring on his back, the result of brutal whippings endured while enslaved. The most iconic of these images, known as the “scourged back” photograph, became one of the most widely circulated images of the era. Taken in 1863, it provided undeniable visual proof of the inhumanity of slavery, galvanizing public opinion in the North and abroad, and remains one of the most recognizable and impactful photographs of the 19th century.

During a medical examination after his escape, Gordon recounted the horrific events that led to his scarred back.

He described a brutal whipping administered by overseer Artayou Carrier:

“Ten days from today, I’ll leave the plantation. Overseer Artayou Carrier whipped me. I was two months in bed sore from the whipping. My master come after I was whipped; he discharged the overseer. My master was not present. I don’t remember the whipping. I was two months in bed sore from the whipping, and my sense began to come—I was sort of crazy. I tried to shoot everybody. They said so, I did not know. I did not know that I had attempted to shoot everyone; they told me so.”

Gordon’s trauma was so severe that it left him disoriented and mentally unstable for a time.

He continued,

“I burned up all my clothes, but I don’t recall that. I never was this way (crazy) before. I don’t know what makes me come that way (crazy). My master come after I was whipped; saw me in bed; he discharged the overseer. They told me I attempted to shoot my wife the first one; I did not shoot anyone; I did not harm anyone. My master’s, Capt. John Lyon, cotton planter, on Atchafalya, near Washington, Louisiana. Whipped two months before Christmas.”

The physical and psychological toll of Gordon’s ordeal was evident, yet his resilience shone through. Dr. Samuel Knapp Towle, a surgeon with the 30th Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteers, wrote in a letter about meeting Gordon. Expecting a man hardened or embittered by such brutality, Towle was struck by Gordon’s demeanor, noting, “he seems INTELLIGENT and WELL-BEHAVED.” Other medical professionals, including J.W. Mercer, Assistant Surgeon with the 47th Massachusetts Volunteers and a surgeon with the First Louisiana Regiment, corroborated the widespread nature of such cruelty. In 1863, Mercer remarked that he had seen many backs scarred like Gordon’s, asserting that the photograph exposed the true nature of slavery, undermining claims of “humane” treatment of enslaved people.

The “scourged back” photograph, alongside other images such as those of Wilson Chinn in chains, had a profound impact. Joan Paulson Gage, writing for The New York Times, observed, “The images of Wilson Chinn in chains, like the one of Gordon and his scarred back, are as disturbing today as they were in 1863. They serve as two of the earliest and most dramatic examples of how the newborn medium of photography could change the course of history.” These images, raw and unfiltered, harnessed the power of the emerging medium of photography to confront viewers with the stark reality of slavery’s violence, shifting public sentiment, and fueling the abolitionist cause.

On July 4, 1863, Gordon’s story and photographs were featured in Harper’s Weekly, the most widely read publication in the United States during the Civil War. The article, published on Independence Day, underscored the irony of a nation celebrating freedom while millions remained enslaved. The images of Gordon’s scarred back provided Northerners with irrefutable evidence of slavery’s brutality, inspiring many free African Americans to enlist in the Union Army. The photographs also circulated internationally, strengthening the abolitionist movement in Europe and contributing to diplomatic pressures against the Confederacy.

Gordon’s escape marked the beginning of his fight for freedom in a broader sense. Three months after the Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863, which permitted freed African Americans to join the Union military, Gordon enlisted as a guide. His knowledge of the terrain and determination to resist oppression made him invaluable. During one expedition, Confederate forces captured him, tied him up, beat him severely, and left him for dead. Miraculously, Gordon survived and escaped once again, returning to Union lines.

Gordon’s escape marked the beginning of his fight for freedom in a broader sense. Three months after the Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863, which permitted freed African Americans to join the Union military, Gordon enlisted as a guide. His knowledge of the terrain and determination to resist oppression made him invaluable. During one expedition, Confederate forces captured him, tied him up, beat him severely, and left him for dead. Miraculously, Gordon survived and escaped once again, returning to Union lines.

Undeterred by this ordeal, Gordon soon enlisted in a United States Colored Troops (USCT) unit, serving as a sergeant in the Corps d’Afrique. He was reported by The Liberator, a prominent abolitionist newspaper, to have fought courageously during the Siege of Port Hudson in May 1863. This battle marked a historic moment, as it was one of the first major engagements in which African American soldiers played a leading role in an assault, proving their valor and challenging prevailing prejudices about their capabilities.

Little is known about Gordon’s life during the remainder of the Civil War or in the years that followed. Like many formerly enslaved individuals, he faced a post-war America fraught with challenges, including systemic racism, economic hardship, and the lingering trauma of enslavement. While the Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery in 1865, the scars—both physical and emotional—endured for Gordon and countless others who had suffered under centuries of oppression in the Americas.

Gordon’s legacy, however, lives on through the “scourged back” photograph and the story of his resilience. His image became a powerful tool in the fight against slavery, exposing its horrors to a wide audience and inspiring action. Today, it serves as a somber reminder of the atrocities of slavery and a testament to the strength of those who endured and resisted it. Gordon’s story, though incomplete, underscores the indomitable human spirit and the critical role of visual evidence in shaping history and advancing the cause of justice.