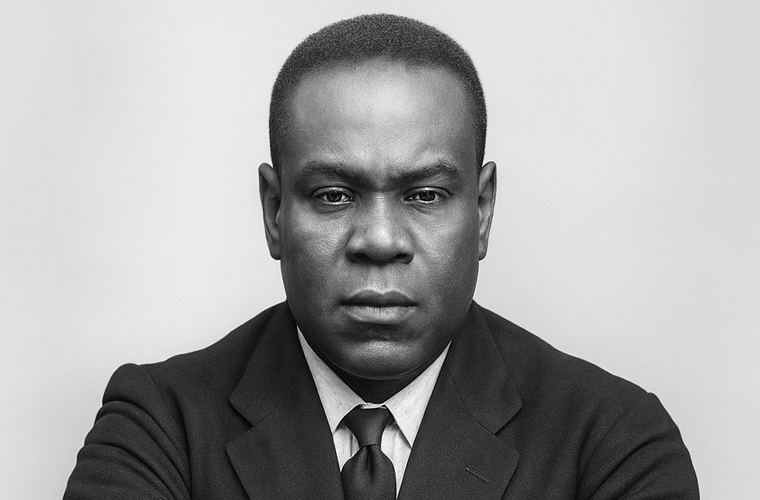

Hubert Henry Harrison (1883–1927) stands as a towering yet often underappreciated figure in African American history, a polymath whose contributions as an activist, orator, writer, educator, and organizer shaped the intellectual and political landscape of the early twentieth century. Known as “the Black Socrates” for his incisive intellect and Socratic approach to debate, Harrison’s life was marked by a relentless commitment to racial justice, black empowerment, and intellectual rigor. His work laid the groundwork for the Harlem Renaissance. It influenced later civil rights movements, earning him accolades from contemporaries like Joel A. Rogers, who called him “the foremost Afro-American intellect of his time,” and A. Philip Randolph, who dubbed him “the father of Harlem Radicalism.”

Born on April 27, 1883, in Concordia, St. Croix, then a Danish colony, Harrison was the son of Cecilia Elizabeth Haines, a Barbadian immigrant, and Adolphus Harrison, a native Crucian. Growing up in the Virgin Islands, Harrison was immersed in a society shaped by a history of slave rebellions, labor protests, and a relatively fluid racial hierarchy compared to the United States. The island’s high literacy rates and significant population of African or mixed descent in middle-class roles contrasted sharply with the racial oppression he would later encounter. Orphaned by 1900—his mother died that year, following his father’s earlier passing—Harrison immigrated to New York City at seventeen, carrying with him a self-confidence and intellectual curiosity forged in the Caribbean.

In New York, Harrison pursued a night school secondary diploma, but his education was largely autodidactic, fueled by voracious reading and a commitment to self-improvement. His Caribbean background, where white hegemony was less absolute, instilled in him a belief in the potential for black self-determination, which clashed with the systemic racism he encountered in the United States. The epidemic of lynchings, Jim Crow laws, and the disenfranchisement of black voters shocked him, catalyzing his lifelong activism.

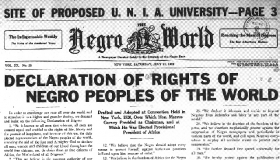

By 1917, he had founded The Voice, a weekly newspaper that became a cornerstone of black intellectual and political life in Harlem. With a circulation of approximately 55,000 at its peak—in a city with 60,000 African Americans—The Voice was a bold platform for black empowerment, featuring editorials, book reviews, poetry, and debates on racial justice. Printed on distinctive pink paper, it was accessible even to those with limited literacy. However, Harrison’s refusal to advertise skin lighteners or hair straighteners, products he saw as reinforcing white beauty standards, led to financial struggles that curtailed the paper’s run.

In 1918, Harrison established the Liberty League, a militant organization advocating for federal anti-lynching legislation and black self-defense, including armed resistance if necessary. This stance put him at odds with more moderate groups like the NAACP, which he criticized for lacking militancy, famously stating that some black leaders had “a wishbone where their backbone ought to have been.” His uncompromising rhetoric extended to other prominent figures. In 1910, he publicly challenged Booker T. Washington’s optimistic claims about black opportunities in the South, publishing a data-driven letter in the New York Sun that exposed racial disparities. Retaliation from Washington’s allies cost Harrison his job at the Post Office. Similarly, his editorship of Marcus Garvey’s Negro World ended in a falling out, and he scorned W.E.B. Du Bois’s “Talented Tenth” concept, renaming it the “Subsidized Sixth” to critique its elitism.

Harrison’s political journey was equally dynamic. In 1911, he joined the Socialist Party, where he organized for two years and became the only black speaker at the 1913 Paterson Silk Strike, advocating for workers’ rights. Frustrated by the party’s reluctance to prioritize black organizing, he left and later founded the Liberty Party in 1924, which focused on international black political unity. His political work was grounded in a belief in self-reliance and global solidarity, reflecting his Caribbean roots and global perspective. Harrison’s reputation as an orator was legendary. Novelist Henry Miller, a young socialist at the time, described Harrison’s ability to “demolish any opponent” with “a few well-directed words,” delivered with a “wonderful smile” and “easy assurance.” His lectures, often emphasizing education’s transformative power, were electrifying. He famously advised, “Remember always that the best college is that on your bookshelf. The best education is on the inside of your head.” This ethos of self-education resonated deeply, inspiring generations of activists and intellectuals.

Harrison’s intellectual contributions extended to fostering the Harlem Renaissance. By mentoring artists and activists and providing platforms through his newspapers, he helped cultivate a vibrant cultural and political scene. His friend Arthur Schomburg, the renowned bibliophile, eulogized him as “ahead of his time,” a sentiment echoed by the thousands who attended his funeral in Harlem. Harrison became a U.S. citizen in 1922 and was briefly married, though his personal life was strained by marital issues and the demands of raising children. His relentless activism left little time for personal matters, and his health suffered under the strain. In December 1927, at age 43, Harrison succumbed to complications from appendicitis during surgery. He was buried in an unmarked grave in Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx, a poignant reflection of his underrecognition at the time.

Harrison’s legacy is profound yet often overshadowed by contemporaries like Du Bois and Garvey. His fearless critiques of racial injustice, commitment to black empowerment, and insistence on intellectual and political independence made him a pioneer of radical thought. Joel A. Rogers praised his “saner and more effective program,” while A. Philip Randolph credited him with founding Harlem’s radical tradition. Harrison’s work prefigured the civil rights and Black Power movements, and his emphasis on self-education and solidarity remains relevant today.