How power, sexism, and male impunity toppled a grand wizard

On the night of March 15, 1925, Madge Oberholtzer received an urgent telephone call. It was D.C. Stephenson, the Grand Dragon of Indiana’s KKK. He wanted her to come immediately. Oberholtzer was an attractive young woman working in a state education program who had met Stephenson at a banquet for the Governor of Indiana. At first, she’d been wary of Stephenson’s aggressive advances but ultimately gave in, attending two dinners with him. On this night however, she brushed aside her reservations and went to his house. When she arrived, she could see that Stephenson, an ardent prohibitionist, was drunk. Some of Stephenson’s men were there. They made drinks and insisted she take one. She was afraid and said no.

But Stephenson insisted more forcefully, and Oberholtzer, feeling powerless, had three drinks — and then vomited. Stephenson told her he was in love with her and demanded that she come with him to Chicago. She said no. What had originally seemed like ardor now had a vicious, uncompromising edge? She was terrified and told him she wanted to go home. But Stephenson was used to getting his way. “No, you cannot go home,” he said. “You are going with me to Chicago.”

A powerful Klansman with a history of political work, Stephenson was a skillful political manipulator who believed he had impunity. As Linda Gordon revealed in her 2017 book on the 1920s Klan, The Second Coming, Stephenson had beaten his previous wives (there had been at least three) and attempted to rape other women and get away with it. As Oberholtzer would later say, “He said he was the law in Indiana.”

Stephenson, who was born to sharecroppers in Houston, Texas, in 1891, got his start working as a promoter for the coal mining and media industries, but it quickly became clear that he was best at boosting himself, mostly by embellishing his résumé. He got involved in the Democratic party and joined the KKK in 1920, climbing his way through the ranks in a mere two years. In 1922, the Klan’s Imperial Wizard named Stephenson Grand Dragon of Indiana. Stephenson was late to his own Grand Dragon inauguration because, as he boasted to the roaring crowd of 100,0000 people, “The President of the United States kept me unduly long counseling on matters of state.”

Madge Oberholtzer was the focus of D.C. Stephenson’s unwelcome affections.

Madge Oberholtzer was the focus of D.C. Stephenson’s unwelcome affections.

The 1920s was the Klan’s heyday, and the hate group held sway in nearly all the venues of power in American society. The same year Stephenson kidnapped Oberholtzer, he nudged a Republican, Ed Jackson, into the Indiana governorship. He had the ear of nearly every politician in the state, exerting influence on legislation the way DC lobbyists do today. He had plans to run for office, perhaps the Senate — or higher. “I’m going to be the biggest man in the United States!” he said.

Stephenson, like his hateful colleagues, made boatloads of money off the Klan, which was infamous for giving kickbacks to its recruiters. He moved into a white-columned mansion in a posh Indianapolis suburb and purchased a yacht, valued at $125,000 — nearly $2 million in today’s sums.

The Klan’s relationship with women was complex. The group had petered out in the years after the Civil War, but reemerged in 1915, rallying against the perceived dark-skinned threat against white women as thousands of immigrants came to American shores. But much to the chagrin of sexist Klansmen, white women had ideas of their own, and those ideas didn’t involve staying at home and waiting around while hatemonger men in hoods got all the glory.

In the years after suffrage, white women were emboldened to enter civic life. White supremacist women were no exception. They rose through the Klan’s ranks, taking up their cause with powerful effect. In fact, arguably, the most powerful person in the Klan was Elizabeth Tyler, the P.R. mastermind behind the Klan’s more expansive vision of hate that included not just black people, but also immigrants, Jews, Catholics, and communists. By the early 1920s, women created their own autonomous arm of the KKK. To the untrained eye, the Klan looked like a friendly place for white women.

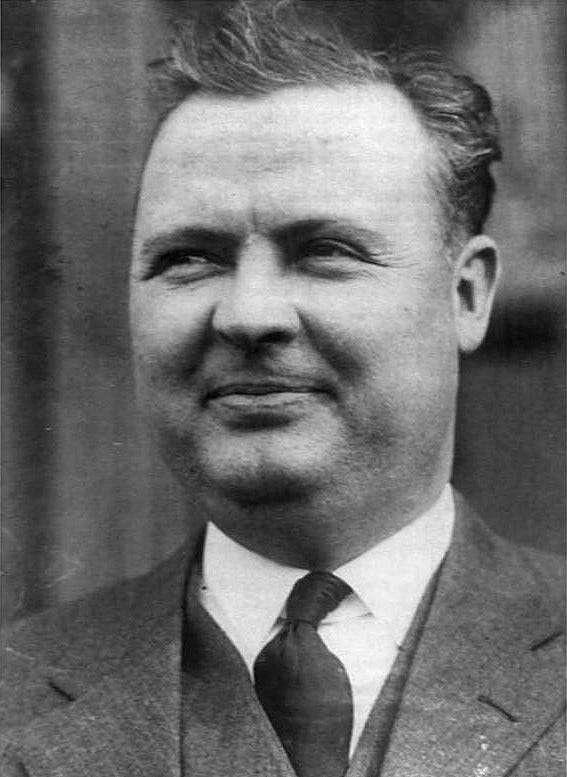

As Indiana’s powerful Grand Dragon, D.C. Stephenson was unaccustomed to rejection.

As Indiana’s powerful Grand Dragon, D.C. Stephenson was unaccustomed to rejection.

Oberholtzer’s story put an end to all that. In the days after the attack, she cataloged each grisly detail for the police. After rejecting Stephenson several times, he and his men had shown her their loaded guns and taken her to a train bound for Chicago. Once in the car, Stephenson took off her clothes and held her down, raping her. “He chewed me all over my body,” she said, “bit my neck and face, chewing my tongue, chewed my breasts until they bled, my back, my legs, my ankles and mutilated me all over my body.”

In the morning, Stephenson took her to a hotel, where one of his lackeys bathed her wounds. According to Oberholtzer, Stephenson apologized, saying “that he was three degrees less than a brute,” to which she replied, “You are worse than that.” She told Stephenson that she needed to go to the drugstore to get some makeup, and one of his men took her. At the drugstore she purchased a box of mercury tablets. Back in the hotel room alone, she took all of them in order “to save my mother from disgrace.”

A few hours later, she vomited blood, and deliriously told the men what she had done. Stephenson insisted that she must marry him and then seek treatment. She said no. “I did not care what happened to me,” she said. On the drive back to Indiana, she screamed in agony and vomited all over the seats, but the men wouldn’t stop. When they finally arrived back at Stephenson’s house hours later, he told her, “You will stay right here until you marry me.” She refused and was taken to a room above his garage. The next morning a servant carried her home. Stephenson instructed her to tell everyone that she had been in a car accident. “You must forget this,” he said. “What is done has been done, I am the law and the power.”

Oberholtzer’s testimony against Stephenson was one of her final acts. She was dead 29 days after the attack — the cause of death likely the combination of infection from the biting wounds and poisoning from the mercury pills. Much to his surprise, Stephenson was arrested not long after. Politicians began denouncing him. In November, he was brought to trial. The gallery was crammed with people trying to get a glimpse of the monster as he fell.

Stephenson was convicted of second-degree murder and sentenced to life in prison. Afterward, he began to name names, revealing that the vast swath of Indiana’s politicians was on the Klan payroll. The governor and several other high ups were charged with conspiracy. The Klan’s image would never recover, and by the end of the decade, the organization was entirely wiped out. It’s a comforting idea. Powerful heads had rolled. Yet, the Klan couldn’t have risen to such staggering power without the nation’s indifference and a groundswell of overt support. One hundred thousand people had cheered at Stephenson’s inauguration — but they were only outraged once he had a white woman’s blood on his hands.